1.1 Mimetics and their grammatical aspects

Mimetics are a highly salient feature of present-day Japanese, though they have been part of the language for at least 1,000 years (Frellesvig 2010: 316; Akita et al. 2014: 183). Akita (this volume) provides a succinct overview of Japanese mimetics within the universal category of the ‘ideophone.’ The impetus to study mimetics in the context of Japanese syntax and morphology is the focus of this chapter. We are interested in how mimetics function in the grammar; based on what we see of their distribution and use, what grammatical properties do they have? The intention is that a closer look at mimetics can offer insight into the internal categorization of Japanese and into the way that various grammatical elements function in the grammar.

In linguistic studies of Japanese mimetics, there are four different aspects which are addressed: the forms of mimetics, their functions, their syntactic categories, and their quite particular meanings (for an overview see Akita & Tsujimura 2015). There are many studies which focus on the first or the fourth of these, and I will not address them at all; with regard to the ‘grammar’ of mimetics, this chapter will focus on just their functions and categories. The theoretical steps which will take us from observing the functions of mimetics to deducing their categories are quite subtle, but, as I hope to show, mimetics provide a valuable perspective on how categories function in Japanese grammar.

1.1.1 Is there a category ‘mimetic’?

It is not uncommon in Japanese grammars to find a separate section or chapter on mimetics, where they are identified as a ‘category,’ more along the lines of interjections, conjunctions, etc., rather than traditionally morpho-syntactically core categories such as Verb, Noun, Adjective, etc. Mimetics are clearly identifiable by their phonological shape, and by the kind of meaning they have. In this sense, there is a class of words in Japanese to which the label ‘mimetic’ applies. As such, though, this label may have no status in the formal grammar, in the sense that no grammatical rules or processes refer to it. For instance, in English, we have classes of words which are based on Latinate roots, or which are deverbal nouns, but there are no syntactic rules or processes which apply only to such words.

1.1.2 Should mimetics be assigned to categories?

The most forceful argument that mimetics should have categories such as V or N seems to be in Kageyama (2007), who proposes that it would be impossible to account for the distribution of the different types of mimetic if such category information were not available. In the context of Japanese, mimetics are typically assigned with respect to four categories: Adjective, Adverb, Noun, and Verb.

Kageyama (2007) considers in some detail different categories that mimetics may have, in terms of this four-way classification. In order for a mimetic word to function in the syntax, with the exception of some of the adverbial uses, it will typically combine with another supporting element drawn from the non-mimetic grammar of Japanese, such as the verb suru ‘do,’ or the copula in some form, or some other marker. We might expect the usual and general combinatory properties of these elements in the grammar of Japanese to be matched by mimetics.

- (1) Verbal: used with a light verb such as suru ‘do’ in a non-copular predicate Adverbial: used within the clause to modify a verbal or adjectival predicate Nominal: used referentially, accompanied by a case-marker Adjectival: used with the copula in a stative predication

Suru is not the only light verb which creates the verbal use: others are iu ‘say,’ kuru ‘come,’ and naru ‘become.’

1.2 Categories in Japanese

In Japanese, the relation is not transparent between morphological criteria for differentiating categories and syntactic rules or processes which refer to different categories. Kishimoto and Uehara (2015) provide an overview of approaches to categories in traditional and generative approaches to Japanese grammar. Tsujimura (2014: Ch. 4) provides a thorough overview of issues of analysis in Japanese morphology largely from a generative perspective.

1.2.1 Inflecting categories: Verb, adjective

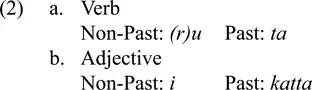

At the morphological level, canonical verbs and adjectives are bound stems which require inflection, and through the form of those suffixal inflections (in (2)), the categories are easily distinguished.

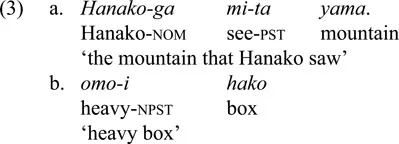

Verb (V) and Adjective (A) are the only categories in Japanese which inflect, taking different suffixes for tense, negation, mood, etc. In these inflected forms, both verbs and adjectives can equally stand in main predicate position in a clause, and both can equally stand in prenominal position, as shown in (3):

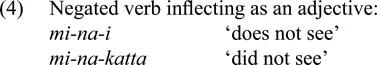

While V and A have clearly separate morphological paradigms, there is some connection between the two categories. For instance, the negative of a verb is formed by suffixing (a)na to the verb root, and the resulting form then inflects as an Adjective – the inflections in (4) are those of the Adjective in (2) – yet negated verbs have the same syntactic distribution as non-negated verbs. In (4) the root mi ‘see’ is followed by the negative na, and then takes its tense inflection:

Although there is a kind of crossover between V and A, and the distribution of inflected Verb forms and inflected Adjective forms is quite similar in Japanese, there is reason to keep the categories separate. Spencer (2008: 1008) shows that there are some specific syntactic contexts in Japanese which select for A but not V. Further, Kishimoto and Uehara (2015) show a different environment in which the distinct category of A is accessed in the syntax.

1.2.2 Non-inflecting categories: Noun, verbal noun, nominal adjective

Japanese has a category of Noun (N) which is as stable and reliably diagnosed as in any other language. Nouns do not inflect (e.g. there is no number or person inflection), and take case markers (e.g. Nominative, Accusative) which are invariant enclitics on NP, following the head noun.

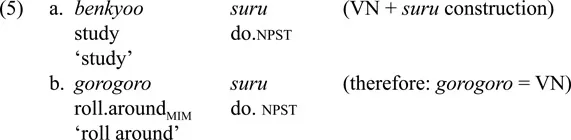

In addition to the canonical categories of V, A, and N, Japanese has some intermediate or apparently mixed categories, namely Verbal Noun (VN) and Nominal Adjective (NA). Unlike the regular inflecting verbs and adjectives, VNs and NAs do not host their own predicate inflection and must appear with other grammatical elements to host tense and other inflectional categories. And, unlike regular nouns, VNs and NAs have meanings which do not seem to be referential, but rather are predicative, roughly speaking, with verb-like meanings attributed to VNs and stative adjective-like meanings attributed to NAs. (5a) shows an example with an uncontroversial non-mimetic Sino-Japanese VN, which forms a predicate with the ‘light’ verb suru ‘do.’ Now the mimetic gorogoro in (5b) fits in the same frame, so we might consider that this mimetic has the category VN, to explain the parallel behavior in (5a). In (5b) and succeeding examples, I use a subscript ‘MIM’ on the English gloss of a Japanese mimetic to indicate that that word is a mimetic.

There is an issue in Japanese grammar as to whether ‘VN’ is its own category, or whether the category is actually V, N, or perhaps either one of the two. In this last case, it would be like a gerund form in English such as singing, which can function in syntax as a V, or as an N. This analysis of V or N is plausible in Japanese (see e.g. Hasegawa 1991; Manning 1993). Focusing here on the ‘V’ categorization, VNs have meanings very similar to regular verbs, but they cannot be inflected. Once this morphological property is recognized, there is no barrier to considering the category of VN as V. It is notable that verbal and adverbial uses of reduplicative mimetics have an accentual pattern in standard Japanese which is different from nominal and adjectival uses (Kageyama 2007: 30; Akita, this volume; Murasugi, this volume). This would also suggest that the informal category label ‘VN’ is actually V, at least in the uses relevant for this chapter.

(6a) shows an example with an uncontroversial non-mimetic Nominal Adject...