![]()

Chapter 1

Birthing the Poetics of Space and Transformation1

I like hanging around

I like hanging

I like my room

I like the school

I like it when my Mom is happy

We’re happy here

It’s boring sometimes

Jacob says we’re homeless

We’re not on the streets

We’re just hanging around.

(Mason, Age 7)

If it is possible to discern beginnings, this book found form on a characteristically bright and sunny afternoon in San Diego some 25 years ago. Mason liked hanging around, doing nothing. In so doing, perhaps he was waiting for what Dennis Wood calls the muse and inspiration that changes the world for young people, the muse that becomes “an unfolding of things to do, an unfolding of things that have no names, … an unfolding of things that do have names … an unfolding of things that have names that can best be left unsaid, or an unfolding of all those things mixed together. Doing nothing is almost everything” (Wood 1985: 9). That day, Mason and I got to unfold some stuff together at the St. Vincent de Paul’s homeless shelter, known locally, and affectionately, as Father Joe’s Village. Once located centrally in the city, the facility moved to a peripheral downtown location and became the biggest shelter in San Diego and the only one, at that time, catering for families.

Mason asked me to take his picture with the Village in the background. To the extent that we existed in bright light and sharply distinguished shadows, I remember that the sun seemed to wash away the context for the deep and meaningful interaction I craved. In the immediacy of that moment, I realized my theories and academic rumination must take a back seat to what I really wanted. My foremost desire was to be liked by Mason, and to have a fun afternoon that we’d both remember. Mason was the youngest of the group that was part of our educational program, and he was different.

Mason outside Father Joe’s Village, July 1991

Father Joe’s Village offered a secure environment on the periphery of downtown, an area that was rife with the kinds of people and land-uses that San Diego’s downtown development interests were trying hard to place on its margins or hide altogether. Lynn Staeheli and Don Mitchell (2008) write pointedly about how San Diego’s redevelopment process unfolds as part of the larger erosion of public space and people’s rights in the face of rampant neo-liberalism, privatization and revanchist policies, which push homeless people to the margins of downtowns and our collective consciousness. Offered a significant amount of space at the periphery of San Diego’s downtown area, Father Joe Carroll garnered endowments from Joan Kroc (of MacDonald’s fame) amongst others to create his vision of a village for the homeless. The shelter housed its families and children on three levels depending on their length of stay. My interests at the time revolved around children’s social and spatial interactions and I used map exercises and self-directed photography to help the children construct representations of their world (the epigram poem contains two photographs that were directed by Mason).

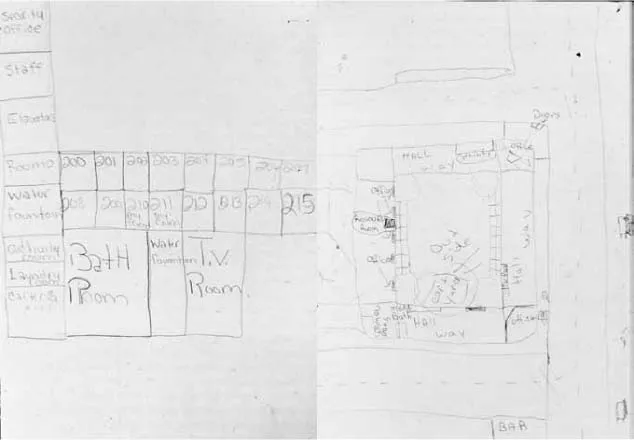

Some of the first maps that the children drew of “their place” were disturbingly constrained. I was reminded of Bill Bunge’s work with children in Toronto, and his admonition that young people should not grow up in high-rise apartments or what he called machine-spaces because those contexts were at best stultifying and at worst dangerous (Bunge and Bordessa 1975).

Kids’ maps of Father Joe’s Village

In Father Joe’s Village back in 1989, the space was stultifying and enervating: bars, security-coded electronic locks and guards carefully circumscribed the children’s locked-down world where the bathroom and laundry room were the best places to hang with friends. The kids attended school on weekday mornings. As the center was funded in part by a religious institution, U.S. laws against the co-mingling of church and state required that the school was separate from the center. Each morning the children (sometimes as many as 30, ranging from 5 to 15 years of age) were escorted past large numbers of adults lining up for breakfast at the center’s kitchen. This was the best free food in town and sometimes up to 300 homeless men and women waited several hours to get fed. Others gravitated to the center for a bed, shower and clean clothes. The single adults were segregated from the families, and the children were carefully chaperoned past them each morning on their way to school. Two certified teachers battled to teach children representing 12 different grade-levels in an over-stuffed classroom whose playground was carved out of, but still abutted, a neighboring junkyard.

The schoolyard

When not at school, the children remained locked in the center. Evenings were spent in the TV rooms on respective floors or hanging with friends in the laundry. Travel between floors was forbidden and access was policed by a security guard at each stairwell. Afternoons were spent in a play area and a classroom on the first floor of the center where volunteers organized educational activities. On occasion, people like me developed educational programs that we hoped were of some use to the kids.

The field-trip we were about to embark upon was based on self-directed photography (Ziller 1990); I wanted to learn how these kids’ lives were interwoven with their environments, how they were contextualized by adult rules and how their perceptions differed from “homed” children. I wanted to understand the commonalities in their experiences. As I stood chatting with Mason, I was confused about my intent and focus. This often happens to me when I leave the security of the university, and the comfort of my books. If a focus on specific research questions (or simply wanting a kid to like me) makes it difficult to fully empathize with, or imagine, children’s experiences, how can I write for them or establish agendas on their behalf? My altruistic concern was to empower kids and find ways to make their lives better; my selfish concern—more so then than today—was to publish great work while simultaneously opening young people to issues of social and spatial justice so that both they and I could fulfill a greater potential. In pleasingly lyrical prose, Gilles Deleuze (1994: 70, 91) describes this as a process of “increasing activity through which we enrich our affective capacities” by increasing our “powers of engagement and lines of flight” through the social and spatial.

This book is about the projection of marginalized young people’s voices and positions, and it is about the ways their affective capacities can be enriched and emboldened politically. It is a serious attempt to highlight the contexts of children through their families, their local environments, their communities and the state in the face of rampant global neo-liberalism, privatization and revanchist policies towards those who find themselves at the margins. It is also about what Elizabeth Grosz calls geo-power, a term I rework as the context of young people pushing back against unforgiving odds and succeeding in creating better places and hopeful times.2 I track research projects from 25 years ago to the present day, and from North and South America, Asia and Europe. The political aim of this endeavor is intertwined with theoretical work that points to better understanding of the relations between young people and their place in the world (cf. Aitken 1994). As Pierre Bourdieu (2008) points out, a political intervention’s chances of success increase the more it arms itself with theory that is grounded in reality. Where Bourdieu and I part company is with his inability to see young people as effective politically actors, focusing rather in what he calls their unrealistic dreams and romantic fantasies of change (Bourdieu 1984, cited in Jeffrey 2013: 147). This book raises the potency of the unrealistic dreams and romantic fantasies of young people embedded in families, local environments, communities and the chimera of state capitalism with a focus on their push for a better place in the world.

The reality of immediacy is that when I was spending time with Mason I forgot about these abstract issues—my politics and my critical theory—because I was embedded in that moment and it was all about our inter-personal relationship. I wanted him to like me, but it was also my hope that the immediacy of the fieldwork was liberatory and emancipatory in the sense that we got to play. I envisage play as a transitional space akin to Donald Winnicott’s space of becoming (1971, see Aitken and Herman 1997). As a student of children’s play theorist and feminist Melanie Klein (1932), Winnicott understood the therapeutic importance of play and the way it projected emotions out into the world. Play encompasses the kind of friendship I want with those with whom I work, for it embodies creativity and affect, and opens me up for surprise and the practice of questioning (Aitken 2001b). This idea of play as a space of becoming may be reworked through Walter Benjamin’s (1978) idea that children’s play is mimetic not just in the sense of copying something but also as a radical flash of inspiration and creativity when something is performed or used differently. Katz (2004, 2011) argues that this puts the idea of play on a revolutionary footing (what she calls a countertopography) where received meanings and relations are refused or reworked (see also Aitken 2001d; Brown and Patte 2012). From Katz’s perspective, children’s play is not just about identity making it is about world making.

Playing with Theory

In the early 1990s, there was little theoretical or practical guidance for the kinds of ethical and practical tensions I faced that day with Mason, although work by anthropologists on what became known as the ‘crisis of representation’ was beginning to unmoor a host of academic practices (Marcus and Fisher 1986; Clifford 1988; Haraway 1988). With this pivotal work, many of us became unsure of how to relate to and write about those with whom we worked. Dubbed as an experimental moment in the human sciences, the crisis of representation became a movement for change. Feminist geographers were using the uncertainty to build robust new ways of understanding based on knowledge that required us to think carefully about how we positioned ourselves and our research (Katz 1994; Nast 1994). Social and spatial theories were broaching the issue of how we related to the world around us from positions that were not necessarily transferrable or translatable. Rather than silencing my voice, they were guiding me away from the structured and somewhat mechanistic ways through which I tried to unravel children’s representations of their worlds to a more nuanced telling that held me accountable to immediacy, feelings, surprises and moments of connection. The crisis of representation was part of the turn towards ‘situated knowledge’ for it un-moored academic practices of writing (Haraway 1988).

This crisis became particularly appropriate for understanding where we situate ourselves in relation to young people. It was based in part on the realization that a quest for an authentic other is not achievable for any group but it is always unfulfilled in children. Epistemologically, we confront the dilemma that cultural difference may not be translatable from children to us. Politically, we face the equally thorny problem of distinguishing between children and us when that establishes a powerful hierarchical dichotomy where we presume to speak for them. And, psychoanalytically, the tendency is often to refer to children as just another kind of “other.” This, then, raises the ethical question of the morality of speaking for others, but children and young people cannot always speak for themselves.

There is a further question, raised by Slavoj Žižek (2006), which is worth bearing in mind to the extent that is relates to scaling up the question of othering and addressing questions about the ways neo-liberal capitalism and globalization relate to young people. In considering a Lacanian perspective on global economic restructuring and capitalism, Žižek suggests that our unconscious is moved from position S (subject) to position $ (a void of negativity that Žižek, from Lacan, calls the big Other). Later in the book I take issue with aspects of Žižek’s Lacanian stance, but I nonetheless find it useful when married with Deleuze’s idea of becoming other through affective capacities and liberatory lines of flight. The question “how are the lives of children and young people othered in the context of social science research and contemporary values?” becomes, in addition, “how do children and young people become the same (e.g. negative, cynical, bored, paralyzed, non-responsive) under the tutelage and strictures of capitalism?” And how do they push back against this tutelage to become something different? In a Deleuzian and Lacanian sense how do they become other to the extent that the strictures of a symbolic big Other on the one hand no longer apply or, on the other hand, are connected to them in stultifying ways?

These questions are heady, and posing them leads me into a myriad of theoretical perspectives that broach fundamental issues of political identity, space, memory, community and, of course, the boundaries and capacities that contextualize young people. What keeps this admittedly ambitious project together is what I am calling the poetics of space.

Poetics, Space and the Inevitability of Transformation

I argue that there is a poetics to space that is highlighted when we are willing to take notice of emotions and affect. Landscape artists, musicians, novelists and poets at times tap into this energy and aesthetics. Social scientists are not always trained to see these energetic relations, although moves to embrace the arts and humanities are not uncommon (cf. Bruno 2007; Dear et al. 2011). That said, often we (artists and scientists alike) are so embroiled in our daily round that we fail to notice overtly the aesthetics of the spaces we move through, and yet the extent to which that energy exists suggests that spatial events are buried deep within us to return when needed. And there is an important politics to these poetics that must be distanced from Gaston Bachelard’s colorful and popular La poétique de l’espace (1958). Bachelard’s poetics are focused on spaces of intimacy and immensity (from rooms and closets to shells and the universe) in an attempt to seek the onset of an image in consciousness. His project is laudable because it requires moving beside time while recognizing the potency of material space and time in the rendering of experiences; it is a moment where time ceases to imprint memory and space and emotion are everything. To the degree that La poétique de l’espace does this, it is an imaginative rendering of images that escape psychology or rationalism, but I am trouble by Bachelard’s allegiance to “pure” phenomenology and his insistence that culture and politics are redundant in understanding the poetics of the world (cf. Aitken 2009). And, importantly for what I want to do here, Bachelard’s phenomenological essences are static, denying the fluidity and mobility of all things in the material world. For years I’ve been intrigued by the ways fluidity, change and extraordinary events heighten emotional responses and perceptual acuities (Aitken and Bjorklund 1988; Aitken 1991), and I am convinced that spaces are active and powerful parts in the ways we as individuals, and we, as parts of families, communities, societies, cultures and politics, apprehend and change the world. There are powerful poetics to spaces and change that Bachelard misses. And, as Grosz (2008, 2010) points out in her feminist re-reading of Darwin, mobility and transformation are not only about politics they are the portents of difference.

Mason was different. And he was much like any other kid. He wanted to love and be loved; he wanted to feel that he fit in, that he knew his place in the world. Mason and his mom were happy at Father Joe’s Village. The happiness detracts from chides that he hears about being homeless from other children and some members of his family. And there is a larger societal and spatial context that propels Mason’s story. It starts years before his birth with the deinstitutionalization movements of the 1950s and 1960s, and the beginnings of a neoliberal disinvestment in social and welfare structures (Dear and Wolch 1985). It continues with the feminization and racialization of poverty in the United States throughout the 1970s and 1980s (Lawson et al. 2010). The marginalization of fathers from family spaces and responsibilities started earlier, and is problematically in place by the economic turndown of the 1990s (Aitken 2001, 2009). All these changes—some dramatic, some incremental—meet up with Mason and me on that sunny afternoon outside Father Joe’s Village. The difference I see in Mason and his mother is a charming and indomitable spirit that connects to this moment and this place in ways that diminish the power (without diminishing the affect) of the wrenching social changes that contextualize his life chances. These changes and the ways they relate to space, purpose and hope are a critical part of this book as are an understanding of the ways our desires are simultaneously who we are and what part we play in larger social formations.

Change is inevitable. A job is lost, a couple falls in love, children leave home, an addict joins Narcotics Anonymous, the political elite take nations to war, a family member’s health deteriorates, a baby is born, a universal health care bill is voted into law. Life comprises events over which we have considerable, partial or little to no control. What I allude to in this introduction and continually return to throughout this book is the notion that the distance between the event and our daily lives resonates a quirky spatial politics. It is from this distance that the possibility to push emerges. Our lives move forward depending upon how events play out in concert with our reactions to them. This book looks at life-changes and the intricate complexities of space that comprise those events. It explores the emotions that undergird the ways change takes place, and...