![]()

Chapter 1

‘The Demon in the Dock’: Domestic Murder in Street Literature and the Newspaper Press1

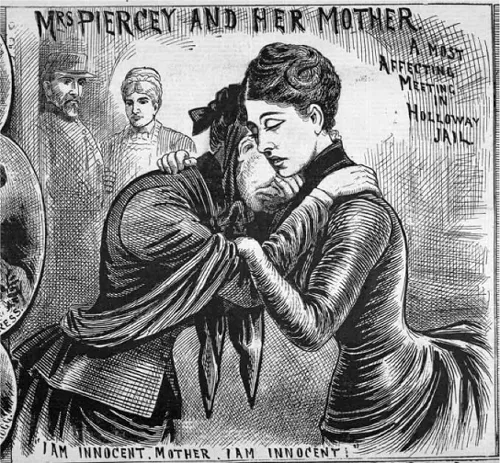

Fig. 1.2 ‘Mrs. Piercey and her mother’. Illustrated Police News, Saturday, 22 November 1890, 1. Source: The British Library

The two illustrations that open this chapter are separated by 62 years, and an ideological shift of immense proportions. The first represents the execution of William Corder in 1828 for the murder of his lover, Maria Marten, as discussed in the Introduction to this work, and in greater detail in Chapter 2. Although the provenance of the illustration is unknown, it is representative of broadside illustration in its portrayal of the isolation of the accused, displayed before a crowd of onlookers, but removed from such community because of the crime committed. Corder is afforded no individuality or humanity – indeed, he is barely detectable in the melee; and, by virtue of the situation in which he is depicted, the inevitable consequence of domestic murder is conveyed.

The second illustration is from the Illustrated Police News, 22 November 1890. The attractive woman portrayed on the right hand side of the illustration is not, as might be surmised, the victim of the crime, but the perpetrator. Her name was Eleanor Pearcey (sometimes referred to as Eleanor Piercey, Eleanor Wheeler or Mary Wheeler), and she was hanged on Christmas Eve 1890 for the brutal murder of her lover’s wife and child. Not only is Pearcey afforded an individuality lacking in the earlier broadside, she is presented to the reader as an attractive woman, in a state of genuine distress at the visit of her mother. The caption for the illustration declares it ‘a most affecting meeting’, and Pearcey’s words appear to reinforce her professed innocence. Pearcey is also at the foreground of the illustration, unlike in the broadside where the figure of the hanged man is at some distance from the reader. The positioning of Pearcey and the focus on her distress invite the reader to a greater degree of empathy than could ever be afforded the anonymous figure of the hanged William Corder. Although, like Corder, Pearcey is the subject of some scrutiny (from the two figures to the rear of the illustration) these observers are drawn with a lighter touch than Pearcey and could easily be overlooked. Their surveillance could also be viewed as oppressive, with the viewer invited to identify with Pearcey rather than with her warders.

These two illustrations are suggestive of a shift in perception and portrayal of the domestic murderer across the period under examination. But the shift is not as simple as one from vilification to empathy. Modes of depiction change over the period, and also conflict with one another, illustrating the cultural tension over the meanings of domestic murder. These tensions and uncertainties are evident in the visual and verbal representations of the crimes, the relationship between these two modes, and the relationship between the press, the Victorian stage, and the novel.

This chapter examines the representation of domestic murders and murderers in street literature and in the newspaper press between the years 1828 and 1890. Given the number of domestic murders which occurred during this time period, some selection of cases was necessary. The Annual Register for each of the years in question carried details of the most notorious cases; this formed the starting point for my research, as the level of publicity generated by a particular murder might be seen as forming some sort of social ‘barometer’. With the breadth of printed crime coverage available, the chapter focuses on murder and execution broadsides (in existence throughout the century, but waning in popularity from the 1860s onwards), the Times, Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, Reynolds’s Newspaper and the Illustrated Police News.2 These publications have been chosen as they all devoted considerable space to crime reporting, and covered an extensive readership: the Times was marketed at a more middle-class readership, Reynolds’s and Lloyd’s were more radical newspapers, and the Illustrated Police News was a prototype scandal sheet.

Through an examination of these publications, it will become clear that domestic murder held a huge fascination for all sections of society, but such fascination was tempered in equal parts with genuine concerns that the health of the nation would be undermined by any disruption to the domestic space. As a result of these fears, the earlier decades of the century saw a degree of consensus in how such crimes were reported, regardless of the professed readership of the publication; this consensus was a means not only of preserving the domestic space, but also of minimizing the potential for class unrest that the nature of these crimes, and the subsequent punishment meted out to the perpetrators, might potentially have aroused. The primary means by which an appearance of social consensus was achieved through the reporting of these crimes was by the adoption of melodramatic tropes, which are examined in some detail in this chapter. As the dominant theatrical mode of the first half of the nineteenth century, melodrama operated within a clear moral framework, and seemed to offer a rigidity and moral certainty that could counteract the crime of domestic drama. The dominant tropes of melodrama which found their way into crime reporting were the visibility of good/evil on the body, and the inevitable triumph of justice and suffering of the guilty. More than this, the press coverage of such crimes transformed the trial into a piece of theatre, further reinforcing the links with melodrama.

As the century progressed, however, particularly from the 1870s onwards, an increasing ambivalence and uncertainty was detectable in the press coverage of domestic murder; this was partly the result of a decline in melodrama as the dominant theatrical mode of the century but, more significantly, was a response to the burgeoning disciplines of psychology and criminology, and concerns regarding the nation’s health and the putative threat of degeneration. Faced with a prevailing sense of uncertainty, the press coverage of domestic murder offered a mixed response, occasionally attempting to paint what we might now see as a more ‘rounded’ or psychologically complex portrait of the accused, but equally often harking back to an earlier time of perceived moral certainty by resorting to the familiar tropes of melodrama. This cultural tension concerning the domestic space, and those who transgressed within it, was also evident in the illustrative content of Lloyd’s, Reynolds’s and the Illustrated Police News, where the illustration frequently belied the written text.

Domestic murder was a particularly disturbing offence for a Victorian readership. Not only did it transcend class and gender boundaries, it also struck within the home, the one area of life deemed ‘safe’. This is not to suggest that ‘the home’ has a transhistorical meaning. As John Tosh has argued:

while a consistent strand of domesticity is to be found in both aristocratic and bourgeois circles throughout the eighteenth century, it was only in the 1830s and 1840s that the ideal of home was raised to the level of a cultural norm. For the middle class above all it had become de rigueur to practise significant elements of that ideal, while those sections of the working class and the aristocracy which resisted it were often perceived to be at odds with the national character (30).

Karen Chase and Michael Levenson make the point that the Victorians did not invent the family

and yet the conditions of mid-nineteenth-century English life – the sheer extent of the home fetish, the maturing apparatus of information (newspapers, journals, telegraph), the campaign for legal reform of the family (infant custody, divorce, married women’s property), the self-consciousness of modernity – gave it a special claim on its own attention (13).

Particularly during the middle decades of the nineteenth century, as Deborah Cohen argues, ‘possession became a way of defining oneself in a society where it was increasingly difficult to tell people apart. Homes … became flexible indicators of status’ (xi).

So central was the importance of the home to Victorian thinking, and so profound was the betrayal occasioned by the crime of domestic murder, it was regarded as ‘domestic treason’.3 In the judge’s passing of the death sentence on Sarah Westwood (found guilty of poisoning her husband in 1843), he emphasized the particularity of domestic murder, accusing Westwood of murdering ‘one whom it was your duty to have cherished and protected instead of to have injured and attacked. I can scarcely conceive a crime of greater enormity or one of a deeper dye’ (Times, 30 December 1843, 7). An earlier broadside held in the John Johnson Collection in the Bodleian Library, Oxford University, tells of Margaret Cunningham, alias Mason, who was hanged for the murder of her husband. The broadside highlights the particularly heinous nature of the crime, identifying the deep-seated fear which it unearthed:

Against the midnight plunderer and assassin we are in some measure guarded by our prudence and ingenuity, and locks, and bolts, and various mechanical instruments, are fabricated for our defence and security: But when a man’s enemies are those of his own house – when the wife of his bosom deliberately imagines and compasses his death – no human prudence, ingenuity, or foresight, will be found sufficient to render abortive her diabolical machinations, or avert the direful catastrophe (‘Treason and Murder’ broadside).

Although the broadside is undated, and the typography suggests an earlier date than the nineteenth century, the same principles hold true. The fear of the ‘midnight plunderer and assassin’, the unknown assailant, is evident here, but is accompanied by a conviction that something can be done to ward off such attacks. No such conviction accompanies the activities of the spouse or sweetheart with murder in their heart; indeed, any defence seems pointless, as nothing ‘will be found sufficient to render abortive her diabolical machinations’.

This was, then, a crime against which there was apparently no defence, a crime which (in the case of poisoning, a particularly popular means of domestic murder)4 required no physical supremacy and could therefore be committed just as easily by a woman as by a man, a crime which did not announce itself and which positively blossomed within the secrecy afforded by the home. Faced with such a threat, the broadside and newspaper coverage of domestic murder in the first half of the century turned to the perceived moral certainties of melodrama as a means of defence.

Readership and the Appetite for Crime

Broadsides were the cheapest, most widely available form of written communication until the mid-1860s, when the advance of cheaper newspapers and periodicals signalled their decline.5 They were also the first publications featuring illustration during the period under examination. A single sheet of paper detailing the news of the day, costing 1d or ½d, and sold on the streets by ‘paper-workers’ or ‘death-hunters’ (broadside sellers who specialized in murder broadsides), such publications were hugely popular, and those dealing with murder particularly so. Murder and execution broadsides generally consisted of a single sheet, with an account of the murder, trial and execution, a poem or song allegedly written by the accused, and sometimes a single woodcut (or more than one for particularly notorious cases). The full murder and execution broadside would generally be preceded by a handbill in quarter-sheet on the fate of the victim, and a half-sheet detailing the particulars of the crime extracted from newspaper reports. More notorious cases might give rise to a ‘book’ of four, eight or more pages, published after the execution.

The abolition of the newspaper tax in 1855 heralded the decline in broadsides, with the ascendancy of the penny newspaper aimed at a populist market. Both priced at 1d, Reynolds’s Newspaper and Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper were not only cheaper and more populist newspapers than the Times, they were also aimed at a more radical readership. Lloyd’s advocated ‘democratic and … progressive’ principles and Reynolds’s was described in The Newspaper Press Directory for 1870 as follows:

Principles: Democratic. Advocates the widest possible measures of reform. It contains much strong nervous writing, thickly spiced with abuse of the privileged orders, which causes it to be eagerly read by a certain class. The news and literary departments of the paper are respectably conducted; and, but for its violent politics, it might be characterised as a good family paper (23, 27).

The various police gazettes that proliferated throughout the period were aimed at a similarly populist market, but with no overtly progressive agenda. The Illustrated Police News, first published in 1864 as a Saturday weekly at a cost of 1d, relied heavily on the visual element to attract readers. A four-page publication, the front page was eventually devoted solely to illustration of the stories contained within, with particular favourites being explosions, mass deaths, carriage accidents, duels, and the dastardly activities of nuns.

Lest we assume that extensive murder coverage was the preserve of these more populist publications it is important to note the coverage devoted to such crimes in the newspapers aimed at a more affluent or aspirational class. The Times carried extensive and detailed crime reporting, with the more infamous court cases sometimes meriting an entire page of coverage for the day’s proceedings, with details of witness testimony printed verbatim; given the lack of illustration in newspapers until the later decades of the century, one page of coverage constituted a considerable quantity of writing. The Daily Telegraph, founded as the first penny daily in 1855 and aimed at a middle-class readership, also featured considerable crime coverage and had achieved a circulation of 200,000 by the early 1870s, clearly showing the success of such an editorial policy.

William Corder’s trial for the murder of Maria Marten (1828) and Frederick and Maria Manning’s murder of Patrick O’Connor (1849), although more than twenty years apart, exhibit the consistent level of public interest in such crimes, with broadside sales of 1,166,000 and 2,500,000 respectively for James Catnach, one of the most successful broadside producers (Anderson, 25). Such figures should undoubtedly be treated with caution but, even if grossly exaggerated, this was the output of only one printer and such notorious cases provided material for dozens of others. Importantly, these same crimes merited similar levels of interest in the Times. The murder of Maria Marten occasioned 21 entries in the Times covering the period 23 April to 20 September 1828, and the Mannings warranted 59 separate articles, from 18 August to 22 November 1849. Even as late as 1889, the case of Florence Maybrick (found guilty of the murder of her husband) gave rise to an astonishing 105 entries in the Times, from 20 May to 5 September 1889, a melodrama entitled A Fool’s Paradise, and a figure of Maybrick in Madame Tussaud’s. These three cases span a time period of more than 60 years, and yet the public appetite for these crimes remained as strong in the closing decades of the century as in the earlier ones.

Even were we to adopt the simplistic notion, then, that the more affluent classes did not enjoy the vicarious appeal of the broadside or the penny weekly, it is evident that the crime of domestic murder was seen to have a cross-class appeal throughout this period. This interest in domestic murder, and crime in general, seems at odds with the arguments surrounding the Newgate novel and sensation fiction (examined in greater detail in Chapters 3 and 4), where the pernicious influence of working-class literature was seen as sullying the middle- or upper-class home. An interest in the murky underbelly of the criminal world clearly predates both the Newgate novel and sensation fiction.

In their coverage of such crimes, newspapers and broadsides did more than simply pander to the public appetite, but actually went some way towards uniting a potentially disparate and fragmented population by the reporting of such crimes. Domestic murders involving the seduction and murder of young women by their employers, or an evident disparity in the sentencing of the labouring classes and the more affluent, could have ignited considerable class discontent. And yet, with the exception of Reynolds’s (examined later in this chapter), the class element of almost all these cases was played down, or completely ignored in the sample of publications examined for this book. This is not to say that Reynolds’s was the only publication drawing attention to class bias; rather that, of the four publications examined for this book, and the particular cases examined, it is notably the only one to focus on class disparity. The one exception to this was William Corder’s trial in 1828, where the minimal social disparity between victim and murderer was actually amplified by the press; this case is examined in greater detail in Chapter 2 of this work, and the reasons for the overplaying of the class card are examined therein.

There were numerous cases throughout the period where either the crime itself, or the treatment of the accused, seemed to offer the press an opportunity to highlight class differentials; but, with the exception of Reynolds’s, the publications examined for this book generally failed to utilize class in their ‘explanation’ of these crimes. Jael Denny, murdered by Thomas Drory in 1851, was the daughter-in-law of an old servant of Drory’s father and had fallen pregnant by Drory; Edmund Pook, Jane Clowson’s ‘young master’, murdered Clowson in 1871; Madeleine Smith, a young middle-class woman almost certainly guilty of the poisoning of her lover, received the verdict of Not Proven in 1857 and walked free. Yet neither the broadsides, nor the majority of newspaper coverage, made any mention of the class disparity inherent in these cases, which is particularly interesting given the subversive element of the canting ballads of the eighteenth century, precursors of the broadsides.

Within the sample of publications that I have examined for this work,...