![]()

1

Four Centuries of Faint Centers

Peter Behrens and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe each paid homage to Karl Friedrich Schinkel and his consummate work, Berlin's Altes Museum. Behrens's German Embassy in St. Petersburg and Mies's Crown Hall in Chicago seem like sequential chapters in an architectural festschrift volume celebrating the great Prussian master's signature achievement (Figures 1.1-1.3). So apparent are the links of these three unusual façades that they are occasionally compared visually to illustrate how formal – if not constructional – continuities reach across modernity's dislocations.1

The idiosyncrasy of Schinkel's façade makes its influence on others easily discernible. Centered and symmetrical, the Museum's grand entry stair reaches out in commodious welcome (Figure 1.1). Yet colossal columns march laterally across our path, as if our approach up the steps is something the building is hardly prepared for and only begrudgingly accepts. A repetitious curtain screens off anything figural, even though the façade takes a frontally posed stance before us. A serial blankness crosses everything, rendering the building rather eerie; infinity visibly overwhelms hierarchy. The colonnade recognizes the building's central axis only at, curiously, its ends, where massive terminal piers bracket the array and inflect hollowly back toward the middle, encountering no obvious visual resonance there (Figure 1.4). Seen in direct elevation, the façade verges on featureless. Seen tangentially, it has more life, exhibiting depth of interplay amongst its somberly monotonous elements (Figure 1.1). Yet even from raking perspectives, it is not traditionally beautiful but instead stern and aloof. The stair acknowledges us and the colonnade's scale commands a certain attention, yet it remains unclear what their puzzling combination conveys.

Anthony Vidler, while discussing the uncanny in architecture, notes the Museum's lack of a recognizably empathic countenance. He links this to modernity's rise, writing: 'we recognize that Schinkel's Museum had itself already begun to suppress what, traditionally at least, might be termed a face.' Schinkel offers 'a stoa, with no formal indication of symmetry save for applied motifs such as steps or the sight of the attic of the central space.' This makes for a 'façade hidden, then, behind a screen.'2 A 'modern' elevation's mechanical objectivity looms here. Even so, Schinkel's centralizing 'motifs' remain haunting in their subjectivity (Figure 1.1). Through them, the Museum does make late amends for its rather indifferent first impression. Secondarily – almost apologetically – they mark its middle. To insure we do not miss them, Schinkel deploys such features with telling redundancy: in addition to the podium stair and attic, a gracious, centralizing piano nobile stair is visible beyond the columns. What really haunts this façade is a last fading glimpse of a figural frontispiece. Flaunting necessitates a past; it cannot be de novo. This study will explore Schinkel's façade as a harbinger of modernity's nascence, but will stress even more how this blending of self-effacement and subtle signaling has long roots in the region's architecture and visual culture.

1.1 Raking view of entry façade of the Altes Museum, Berlin, 1823–30, Karl Friedrich Schinkel. Photo: Randall Ott.

Both Behrens's and Mies's façades reprise the Museum's enigmatic mixture of initial reserve and late embrace (Figures 1.2 and 1.3). Of course the similarity could reflect nothing more than reverence rendered literally – perhaps they are just heartfelt acknowledgements of a respected forbearer's prominent if peculiar creation, emerging out of a conversation amongst masters couched intentionally in an esoteric language only they know well. Yet the group shares further idiosyncrasies. While frontal in bearing, all three are sited to be first seen obliquely.3 Formally symmetrical centrality is not only blanked over by adamant repetition, but is shown to us from an unusual, glancing prospect. Suspicions emerge that an underlying system operates here. In examining these façades' interrelationships and contextualizing them amongst related examples, this study will acknowledge a previously unrecognized, 400-year regional tradition –what I will call the 'screen' façade.

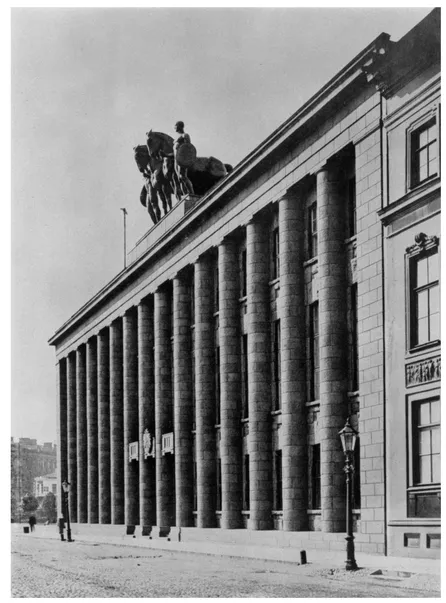

1.2 Raking view of entry façade of the German Embassy, St. Petersburg, 1912, Peter Behrens. Foto Marbug/Art ReCredit, NY.

Undoubtedly Schinkel here influenced Behrens and Mies, but was himself influenced by many other architects before him. And yet others stand in between these masters. The mode had currency in German-speaking Europe and nearby areas and displayed

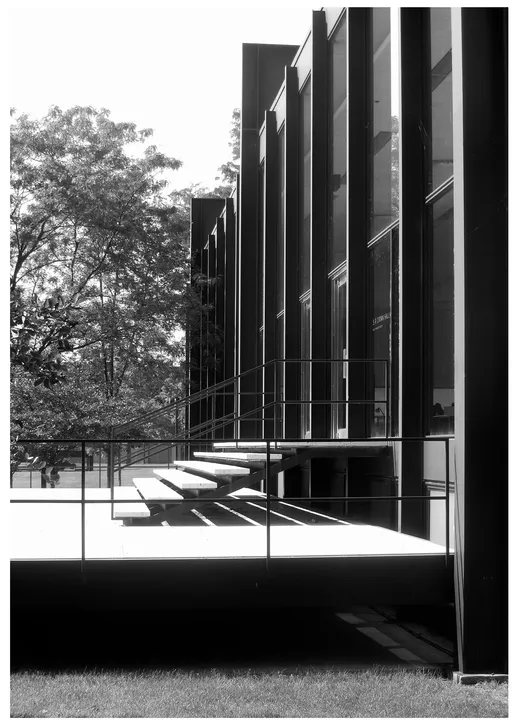

1.3 Raking view of entry façade of Crown Hall, Chicago, 1950–56, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Photo: Randall Ott.

1.4 Full frontal view from the Lustgarten of the Altes Museum, Berlin, 1823–30, Karl Friedrich Schinkel.

an invigorating range of variants. Along with grandly columnar examples, like Prague's imposing Czernin Palace (Figure 1.5), are quieter cellular configurations – like Munich's Postal Headquarters (Figure 1.6). The series exhibits, as Jacob Bronowski puts it, 'hidden likeness in diversity.'4 Schinkel, Behrens and Mies made 'type specimens' within a regional genre. To borrow George Kubler's language, they enjoyed a 'climatic entrance' within a larger sequence and created 'prime objects.' Compositionally, each relied on what came before, but entered the series at a point:

... when the combinations and permutations of a game are all in evidence to the artist; at a moment when enough of the game has been played for him to behold its full potential; [and] at a moment before he is constrained by the exhaustion of the possibilities of the game to adopt any of its extreme terminal positions.5

1.5 Full façade view of Czernin Palace, Prague, 1669–1720 and 1746, Francesco Caratti.

1.6 Raking view of Postal Direction Office [today the 'Art Deco Palais'], Munich, 1922–24, Robert Vorhoelzer. Photo: Randall Ott.

In addition to these prime objects, the three architects each also contributed additional if less influential screens to the series.

Glimmers of the system they sequentially codified are apparent as early as prominent monuments like Heidelberg's 1559 Castle and Nürnberg's 1622 Rathaus. Additional well-known German architects like Friedrich von Gärtner or Leo von Klenze figure into this study's chronological review, as do eminent Austrians like Adolf Loos and Otto Wagner and the German Swiss Hannes Meyer. Yet importantly, the series of 100 plus buildings mostly contains works rarely discussed in the English language literature, bringing little-known practitioners new attention. Many of these façades will be considered only in passing, but in addition to the prime objects by Schinkel, Behrens and Mies, I will give about two dozen others extensive treatment. Fresh interpretations can emerge about well-known works by situating them in regional context. Further, as Kubler notes, 'extreme' terminal positions do appear: less savory characters serving the Nazis will show us how extreme the screen format can become. The book addresses Nazi works ranging from the grandly ceremonial (Albert Speer's Chancellery) to the horrifically 'industrial' (a crematory at Auschwitz-Birkenau). The screen's dyadic nature is seen nowhere more clearly than in that period – where the mode's blending of reactionary and progressive aspects garnered it many adherents. We will briefly examine other regions to see how uniquely German this mode is. The most prolonged non-German usage will be found among other twentieth century totalitarian groups, both leftist and rightist. This may make us wonder about the underlying phenomenological signals incumbent in such a mode. If I often stress the screen's tinge of eeriness in early times, this is only to lay the groundwork for our perceiving the potentials that modernity's totalitarians apparently recognized.

Six Components

In his book The Power of the Center, Rudolf Arnheim identifies the tension between centrality and repetition as fundamental to Western art. He notes that this is often manifested through interaction of the circle and Cartesian grid – two distinct systems that when put together 'serve our needs perfectly.'6 Their complex relations allow for diverse expressions. Much of the enigmatic mixture encountered in these façades derives from a regionally peculiar attitude toward this.

I define the screen using six interrelated components, each having some relation to this core dyad. The sheer reiteration of this one theme within this façade system is itself noteworthy, and I will argue ultimately that this has its own distinct meaning. Of the six, the first three components are generalized: many buildings of virtually any era or culture would satisfy them. The other three are more specific and unusual, increasing progressively in rarity and diagnostic utility. Often these will necessitate extended commentary. The last component is the most distinctive, forming an interpretive key revealing much about the system's predisposition.

- Repetitiousness: The fundamental articulation – either columnar or cellular–is of evenly arrayed, identical elements, reaching toward totalization. The bay count exceeds what we can enumerate at a glance – a dozen or more.7 Acknowledging the experiential distinctness of horizontal and vertical, the façade is predominantly horizontal, fully occupying our lateral field of vision. Internal programmatic differentiation is suppressed. No widening or alteration of the essential array occurs at center to indicate passage.

- Austerity of Profile and Detail: No overarching, global, centering device such as a dominating pediment or dome exists. The building's silhouette is simple and rectilinear. This austerity in profile is matched by austerity of detail: both consist predominantly of the sharp interaction of horizontals and verticals. If multiple wings occur, the screen-like face should have relative autonomy.

- Centralized Entry with Internal Axis: Entry is at geometrical center and reinforced internally by axial spaces. The...

![1.6 Raking view of Postal Direction Office [today the 'Art Deco Palais'], Munich, 1922–24, Robert Vorhoelzer. Photo: Randall Ott.](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/1630106/images/fig00008-plgo-compressed.webp)