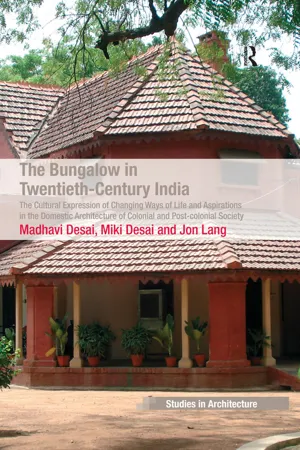

![]()

1

Introduction The Bungalow: Its Origins and its Evolution in Twentieth-Century India

Bun.ga.low\n [Hindi banglo, lit., (house) in the Bengal style]: a usu. one storied house of the type first developed in India and characterized by low sweeping lines and a wide varanda.

Webster’s Seventh Collegiate Dictionary, 111

The origins of the single family detached house as a residence can be traced back two thousand years (King 2004). While its form that we know today can be said to have had multiple origins two are basic to the Indian context: the Bengali and the English country houses. The term bungalow as applied to single family detached houses is, however, clearly Indian, and specifically Bengali in origin.

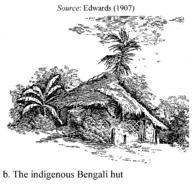

The fundamental building type of Bengal was the pavilion. ‘Its singular persistence as the idea of dwelling (vastu) further clarifies the culture of the Bengal delta (Haque et al. 1999: 9). It is a freestanding, single room, single storey structure and consists of a bent roof, a canopy chhad. This bangla roof type is a defining element of the Bengali vernacular architecture. The walls, placed well within the perimeter of the roof, are permeable and the verandahs, terraces and the semi-enclosed nature of the site reinforce the pavilion like quality. The materials used were those provided by the delta; clay is the predominant material but bamboo and timber were also available. In rural Bengal the house design has not changed much over the past three centuries although new materials are often employed now and we see less of the chhad roof form. The hut’s resilience as a type stems from it withstanding the torrential rain and sheltering its inhabitants from the intense heat of the sun. While it was and is an impermanent structure it gave the world the term ‘bungalow.’

As defined in Webster’s the word ‘bungalow’ is Anglo-Indian in origin and derived from the word bangla meaning ‘belonging to Bengal’ or simply ‘of Bengal’ in Bengali and many other Indian languages. As early as 1676 British East India Company officials referred to ‘Bungales or Hovells ... for all English in the Company’s service’. By 1711 there were references in East India Company manuscripts to a ‘Dutch bungelow’ on the banks of the Hooghly. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth century there are references to houses in India as ‘bungula’ and ‘bungalo’. By the mid-nineteenth century the word bungalow was in common use. An 1847 description cited by George Edwards (1907) describes what the bungalow of the era was.

The second antecedent of the bungalow form lay in contemporary England where the single family detached house took two forms: workers’ rural cottages and the rural villa. John Lockwood Kipling (1837–1911), one time professor of architectural sculpture at the Sir Jjamshedji Jeejeebhoy School Art in Bombay (now Mumbai) believed it was the latter to which the Anglo Indian bungalow owed much (King 1995).

The workers cottages were small, single-storey in height with one or two rooms (Loudon 1939, originally 1834). The villa was grander. The term, ‘villa’, is Italian in origin. It came to be applied to elegant two-storey houses of upper-class in rural Britain. In the twentieth century the term ‘villa’ came be applied to a variety of houses: detached and semi-detached homes whether located in rural or suburban areas.

The Meaning of 'Bungalow'

A 1793 description of bungalow cited in Hobson Jobson confirms what has been noted above. It runs like this:

Bungalows are the buildings in India, generally raised from the ground, and consist only of one storey: the plan of them usually is a large room in the centre for an eating and sitting room and the rooms at the corner for sleeping; the whole is covered with one general thatch, which comes down low to one side; the spaces between the angle rooms are viranders or open portices ... sometimes the centre viranders at each end are converted to rooms (Yule and Burnell 2006, originally 1886).

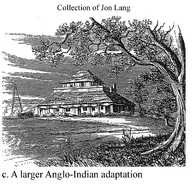

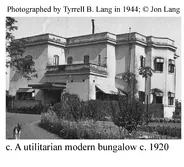

In much of the English-speaking world today a bungalow still refers to a detached, generally single-storey dwelling, occasionally with a verandah. There are departures from this general meaning. In North America, it refers frequently, to a one and a half storey dwelling, often with an Arts and style and characteristics. More specifically, in the United States, a bungalow can be anything from a small two-storey country house, to a building without dug foundations and large multi-storey such houses. In the west of the country the Californian bungalow owes much to the New Mexican hacienda, also rural house form, of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Reeve 1988). Even in India two-storey indigenous and Anglo-Indian bungalows were quite common (see Figure 1.1c).

These definitions are a point of departure but the meaning of the term bungalow is interpreted somewhat differently in different places and, in the twentieth century, in India it came to have a meaning really quite different from its Bengali origins as it evolved over time and regions.

The Meaning of 'Bungalow' in India

The bungalow was originally a dwelling conforming more to a colonial ‘Indo-European’ than the traditional Indian model (King 1984: 55). In India, and in Southeast Asia, ‘bungalow’ implies a freestanding, ex-urban dwelling. In the nineteenth century it was usually considered to be of one storey. Increasingly in India in the twentieth century, houses of two or more storeys were still considered to be bungalows. The bungalow form was adopted and adapted by the indigenous populations in India to suit their needs and taken by British business people and officials to other parts of the world (seeFigure 2.28for an example). The word bungalow is, however, now used to describe a variety of residential building types both in India and elsewhere in the world.

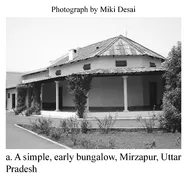

The bungalow in the second half of the twentieth century in India meant an ‘independent or an isolated dwelling unit’. Examples of bungalows in their historic context are shown in Figure 1.2. All the houses shown in the figure are known in India as bungalows except by the most pedantic. The defining meaning of bungalow was and is a dwelling built within a plot of land that is clearly defined by boundaries. As such it stands in strong contrast to densely-packed urban houses of traditional Indian cities.

1.2 The evolving use of the term ‘bungalow’ for single family detached houses

The bungalow in India was and is a large house surrounded by open space with trees and garden, enclosed by a wall or a fence. Over time the sites have shrunk in size and one dwelling is separated from its neighbours only by the minimum distance specified in building codes designed to stop fire spreading. The nature of the bungalow was originally a response to the climate having a high ceiling, being airy and enveloped by a verandah with a European portico in the front, but in colonial society it soon acquired socio-political meanings of status. In a post-colonial world it still does.

The buildings and urban designs associated with the colonial enterprise, of which the bungalow and the residential areas of single family detached houses sitting in their compounds is highly representative, was a product of a political and economic system as well as a social and cultural setting for Anglo-Indian ways of life. The bungalow was a dwelling type that was absorbed into Indian middle-class life. It evolved in the twentieth century as ways of life changed due to technological changes, the evolution of family structures and the roles and expectations of family members. New house forms emerged from a loose amalgam of antecedents that included not only the bungalow but other indigenous houses both in overall form and internal organization. These new forms had antecedents in the various Indian house styles and internal arrangements of the nineteenth century which, in turn, were based on earlier ways of life and what were regarded as appropriate. Over time, the very nature of the bungalow was shaped by the changing cultural demands of India.

Evolving Cultures and Evolving House Forms

House form and culture are intertwined as are house form and climate (Rapoport 1969). One of the purposes, indeed the fundamental purpose, of any building is to provide shelter for a set of activities. Once, however, this basic need is served well enough, people seek to have their higher aspirations met (Maslow 1987; see Chapter 3). For this reason the form of houses and their location in relationship to each other, the services needed by people to meet their everyday requirements and the aesthetic character of the building often seem to make little sense from a climatic viewpoint. Houses often seem to have little relationship to their geographical context although responding climatic necessities is always a concern (see Chapter 6). The form of the built environment at any time in history can be seen as an adaptation — successful or unsuccessful — of the natural environment by people working within a cultural frame.

The ways in which houses are configured produce properties that afford specific behaviours and preclude others. The sum total of the affordances1 of a configuration, or pattern, is the totality of possible ways it can be used by people (or other species if they are of interest). Many people are prepared to tolerate high degrees of physiological discomfort in houses for other, often symbolic, aesthetic, status-related ends that are perceived to be central to their identity. The interior layouts of houses, how they are located in relationship to each other and to streets, and their exterior appearance — the face they present to the world — are material representations of a culture. As behaviour patterns and aesthetic values change so do standard house and housing forms. The nature of houses at any point in history represents the contemporary aspirations of their owners to the extent that their resources — emotional and financial — allow. One of the characteristic developments of the twentieth century was the rising affluence of the middle class and the appearance of the consumer society in India. The houses people chose for themselves reflected this new financial status. A houses is, after all, a symbol of who one is (Cooper 1974) and of one’s membership within a group, both socio-economic and cultural.

Many different activities take place within the give and take of family life. A family serves many purposes that vary by family type and for different members of the family. These include economic, nurturing, sexual, educational and ceremonial purposes. They change as the family changes over time and as the broader culture impinges on family life. In maintaining and running a household, a number of specific activities are reflected in the layout of dwelling units. The religious strictures of Hindu and Muslim society explain much.

The Indian subcontinent has seen a number of waves of migration and three thousand years of ethnic and religious struggles for power. Throughout its history India has been a Hindu-dominated country. The Mughals conquered India and stayed, changing its ethnic and religious composition; Britain colonized India and while leaving few people behind on quitting the country, broke the continuance of tradition in many areas of life including house form.

Household activities are not all of equal importance in analysing the evolution of bungalow types in India during the twentieth century. In some places in India religious practices have had no impact on the design of houses; often socio-economic constraints and the availability of cheap materials at hand have dictated everything. For the poor it is a way of life. This book is, however, about the middle-class.

The Twentieth Century: The Shift from a Colonial to a Post-Colonial Society

Cultures change. Sometimes these changes are rapid and at other times incremental. Some new ideas develop independently within a culture; others are adapted because they provide the affordances that achieve specific objectives more easily or more comfortably than existing patterns. Some patterns are adopted because they are seen as prestigious or fashionable.

The twentieth century was tumultuous for India as it was for much of the world. There were major movements of people so that in the cities people of different cultures and socio-economic statuses often lived cheek by jowl. Some of these migrations were due to economic necessity; others to political upheavals. These movements, industrialization and political changes and the general increase in wealth and thus greater opportunities for people to express themselves have sped the process of cultural change from a pattern that had previously been slowly evolving. The processes of globalization that began with the colonial enterprise have sped up the influence of international architectural ideas.

At the beginning of the century the use of electricity was in its infancy. The introduction of automobile, radio, telephone and cinema was yet to come. Refrigerators were unheard of. Change was rapid. All these elements were part of everyday life for the middle-classes in India by the end of the 1930s. Ways of family life thus started to change radically. International influences came thick and fast. People’s aspirations changed. Family structures began to change; the role of men and women began to evolve. Life began to be turned upside-down. Radical changes occurred in the size of families, their structure, the relationship of their members to each other and the roles of servants and other household members. These aspects of a culture are accommodated to a greater or lesser extent by the structure of dwelling units and residential areas. New house forms emerged that showed an amalgam of the bungalow type with indigenous types. Some...