![]()

1 Introduction

This book is about the nature of HRD. I disagree with the view that HRD is a subset of HRM, the poor sister of the real world of management. In this book I argue that HRD is much, much more than that. Those people involved in the initial breakdown of the field of ‘management’ into its subsets, and those who have just followed in their footsteps without considering the implications of such categorisation, have not come to grips with the importance of the influence of development in forming our very existence. I posit that ‘HRD’ is shorthand for what is at the core of our being and our becoming. HRD is thus at the centre of our understanding of our lives, our relationships with others, and the emergence of our futures.

I appreciate the boldness of these claims, and in this book I seek to support my ideas with evidence from a wide variety of sources, from evolutionary psychology, Greek philosophy, and arguments about climate change, to name but a few. Because this book is about people and relationships, and the way in which individuals and societies work together, I also make use of evidence from people and situations that I have encountered and engaged with. Elements of this book could therefore be seen as autobiographical, but the stories are not told with this intent. My aim is to use parts of my experience almost like case studies in order to add strength to my line of thought.

When teaching quantitative methods, one of my favorite examples showing the problems of correlation versus causation is associated with childbirth. There is a common belief that the older the woman the more likely the child is to have birth defects and later problems, and indeed there is a correlation between the mother’s age and genetic defects. However, as I point out to my classes, this is not a causal relationship. The majority of older women have older men as partners, and an examination of the data shows that it is the age of the man, not of the woman, that is of importance here. The biological explanation for this is that the woman’s eggs are all formed at birth whereas the man’s sperm is continually created anew through cell division. As the man ages there is an increasing (though still small) chance of mutations developing (LePage 2014).

I have used this example many times because, as well as demonstrating the dangers of correlation, it also demonstrates the reach of a patriarchal society that assumes such problems are attributable to women. Much fun can be had with this when encouraging debate with students. I was surprised, however, when one person came to me several years later, and explained how this point had radically altered her life. She had been in her late thirties when we met and did not wish to risk bringing into the world children with genetic problems associated with elderly primagravida. However her partner was much younger than her and following my lecture they explored what I had said and decided to risk a family. They now have very healthy children.

I had seen this from an academic point of view: as an interesting example to rouse thought and discussion. I associated it with norms and assumptions. After she came to me to thank me, however, it was also about the immediately personal side of family life and of someone I knew and liked well. The critical dispassionate academic balanced against the individual and personal. This book is also about those two aspects of our existence, the quantitative and qualitative going hand in hand. I draw upon our vast human experience of scientific knowledge whilst also pulling in my own individual experience and understanding, as do we all when we try to make sense of the world. I reject the idea that the world can be seen and understood entirely through either the scientific lens or the personal lens.

We live in a world of structure; we structure our conception of our world. The very way in which we perceive and make sense of things has structure created through our biological perceptual processes. As individuals we create our own, unique, understandings and conceptual structures, forged through genetics and experience. As societies we develop shared structures, and shared understandings. Collectively we have created a world of structure, have refined and defined, have honed our knowledge to create edifices of science and learning. Our understanding of cause and effect, and the manipulation and building of relationships between abstract concepts, have enabled us to go beyond our evidence-based existence to speculate, experiment, and create new understandings and structures.

We need the surety of such scaffolding, we need glossaries and definitions, we need rationalistic thinking and scientific breakthroughs, mathematics, statistics, and the hard sciences. We all need to understand them because in understanding them we can also understand their frailties and appreciate when they might not be of much use. We need to be able to understand when to step away from those structures lest they become prisons. We also need to appreciate quite how fragile they might be.

I have a background in experimental psychology and I specialised in test theory and cognition at a time when computers were large and housed separately in hot noisy rooms and PCs didn’t exist; a time when statistical calculations were all done by hand, including multivariate analyses. Nowadays, we plug some numbers into the computer and out pops the answer. We risk losing the deeper understanding of how the test works and what it really means. The mere existence of statistical results gives the analysis the appearance of being important and correct. However, my knowledge of quantitative methods makes me wary of the way in which they can be used to provide authority.

The application of lots of multisyllable words and statistical analyses gives the appearance of accuracy and truth. Talking in the third person whilst using obscure language provides authority (Lee 2010). What it can hide is sloppy thinking, erroneous use of statistics, and personal bias. As with the example above, false correlations slip into our cultural understanding and are rarely challenged. If we delve into the data that we are presented with, we can find personal and cultural biases intruding. My preference is, therefore, to balance the presentation of data with an open acknowledgement of the personal side of its impact. In this way people can make up their own minds about the import of what I am saying and the biases I might be exposing. Of course this does rely upon me being as open as I can—to myself as well as to others.

The account I present in this book is not about traditional ‘HRD’ or ‘HRM’; it is not about practice, or theory, or professionalism, or ethics, or any such area of study—though it does touch upon all of these things. This book is much messier. It is about us and our relationships: how we change and change others—and how others change us; how we interpret and structure and manage our lives—and how we don’t. This book balances the personal and the wider picture, across both the content and the delivery. For want of a better word or description my approach is best described as autoethnographic in that I use my own experiences as a basis upon which to build a bigger picture (though see Chapter 5 for a discussion of this).

Although my experiences are unique to me, they are just a springboard that I use in my attempt to pull together an integrative model of holistic agency that I developed in the early 1990s and have been playing with ever since. I tried to publish my model at that time, and got good reviews, but also rejections—the reason being, quite rightly, that I should either publish it as a series of papers, or in a book, as it was too large to publish in a journal. It was at this time that I developed the Studies in HRD series with Routledge, with my book intended to be the first in the series. I then had a cerebral haemorrhage and the book remained a nice idea, and the series flourished without it! Since then, my areas of enquiry over the years have been widespread. Because of the width of my model I never really settled to focus on one research area; instead, driven by the 7,000 or so words needed for an academic publication, I looked at one or another small corner of the whole so that each paper I wrote only reflected part of my interest. Also, because of the scope of my interest I have published in a wide range of outlets, some quite obscure. In this book, long in development, I bring together my ideas in a way that presents a more coherent whole. Each chapter is based around a paper I have written, and, for those who are interested in the history of such things, I have given details of the antecedents of each chapter in Chapter 20 at the end of this book.

Section 1. Setting the Scene

The book comprises five sections. The first section sets the scene, looking at what we might mean by HRD, what the roots of HRD might be, how we might seek to understand HRD, and what methodological choices we have in furthering our interpretation. The first two chapters in this section focus upon what HRD might be, whilst the last three focus upon methodologies. I start by asking ‘what is HRD?’ in Chapter 2. I suggest that there are two main ways of looking at the world—the scientistic, being world of structure, and the phenomenological, becoming world of agency. I argue that HRD cannot and should not be defined, yet we need to be able to focus on what we are looking at, so how can we know it? If we cannot define it, can we describe it in other terms? To some extent, the rest of this book fans out from this one paper to give the wider rationale.

Chapter 3 presents two key archetypal structures that dominate the way in which we perceive the world—namely, self and other, and agency and structure. These archetypal structures are derived from evolutionary psychology. They underlie my model of holistic agency and I take the organisation of this book from them. These archetypal structures provide a conceptual basis for my description or understanding of the way in which we interact with others and make sense of our existence in the world—in other words, they explicate the roots of HRD. In this chapter I also start the process of dissecting the apparent surety of our existence, or at least our understanding of it. I describe the development of humanity through the lens of complexity and co-creation, and present the notion of holistic agency as a core concept of the book. The following four sections of the book link directly to the polar ends of the archetypal structures, so there is one section each on self, other, agency, and structure. The idea of holistic agency that I developed in this chapter permeates the book and is addressed more directly towards the end of the book.

Chapter 4 looks at the representational nature of our thoughts, our language, and our depictions. This is an important theme throughout the book—how we know what reality ‘is’ and how we construe our own reality. When we question our understanding of reality in this way we are also questioning the distinction between epistemology and ontology. In a world of transience and interpretation how can we know anything for sure? It follows that in making sense of the world, autoethnography is a powerful methodological choice for HRD, and, to a large extent, that is the approach adopted here.

Chapter 5 exposes the nature of the book in more detail, through an exploration of methodological choice. Our methodological choice depends upon the way in which we want to find meaning and the sort of meaning that we focus upon. I suggest that the nature of HRD lends itself to mixed methods in which quantitative statistical information is interpreted alongside a more qualitative and personal understanding.

The final chapter in this section (Chapter 6) is the only one that is not written by me, although I am the focus of it. One of the problems of using self as a springboard or basis of wider understanding is that it is easy to fall into the trap of self-referential narcissism, and so I was reluctant to include the interview here. One of the referees of this book, however, reminded me that knowledge of the author and their biases is an important aspect of understanding and judging the value of what the writer is attempting to say. I therefore include the interview in the hope that you, the reader, will examine it with a critical edge so that it informs your analysis of my arguments.

In this first section of the book, therefore, I present a typology of typologies built upon two archetypal constructs. These are derived from evolutionary psychology and are a fundamental part of how the human condition has developed. In order to understand and work with the implications of these notions we need to adopt (or at least borrow) the language and perspective of complexity theory. Through this process I have tried to come closer to what I would see is the nature of HRD. That nature is about process and I describe it as the glue between the representations. For the want of a better term I call it holistic agency. This section is, therefore, largely conceptual in nature. However, in order to make sense of our search for meaning we need to balance a scientific focus on facts with an understanding of the personal and individual. In a similar manner, I shall argue that holistic agency is about construing both the wider picture and action within it. In order to develop a balanced picture, we need to step aside from the conceptual on occasion, and consider the individual and the world of action. That is the reason why much of the research in this book is presented as from an autoethnographical stance, and it is also the rationale for the following four sections of the book.

The Rest of the Book

The next four sections are devoted to the four polar ends of the two archetypal constructs that are identified in the first section. As discussed in Chapter 3, as our ancestors developed the pattern of bearing live young that needed parental care for survival they also developed the pattern of behaviours and emotions that bonded parent and child in a dependent relationship. Thus their first great archetypal system has to do with attachment, affiliation, caregiving, care receiving, and altruism. As the child grew, was replaced by other children, and eventually became a parent themselves, so ‘self’—and as a necessary and integral part of that process, ‘not-self’, or the ‘other’—emerged. Therefore, that the first fundamental dynamic played out in each person’s life is that of self and other. This pervades the whole of our existence and is the core of self-development literature.

The nature of an archetype is that it does not really exist; it is not achievable. Instead, it is a conceptual embodiment, a pure vision of what is being alluded to. As will be seen in the text, none of the chapters are, or can be, exclusively about one or other of the polar ends. Each can only be known by what it is not, and so in looking from one archetypal pole to another, each contains elements of the other. Therefore, although the following sections are separated, I trust that if you read through you will find many links from one section to another, and question why on earth I clustered them as I have. I can only say that this was a rather awkward exercise and was done for the sake of clarity. I hope, also, that I have offered a hint of conceptual coherence. This can perhaps be better described visually, through a thought experiment to which you will unfortunately need to imagine colour, as this book does not stretch to colour illustrations.

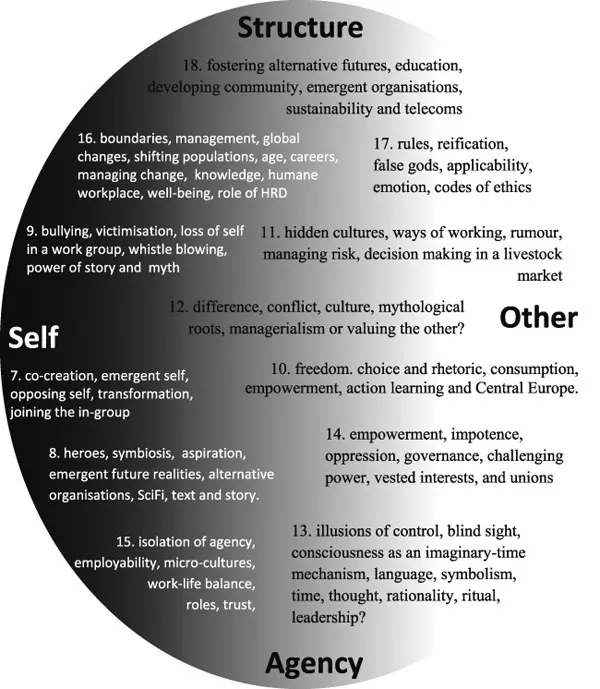

Figure 1.1 Representation of Sections 2 to 5

Imagine a dot of pure red colour that gradually dissipates as it spreads out. That could not represent an archetype, as the colour red does exist and is achievable; however, it is that sense of dissipation from an intense core that I am trying to describe here. As an aside, it is interesting to note that even the correct wavelength for red light is hard to define. It is given as a range (~ 700–635 nm) and has no one singular point. Imagine a colour red dissipating across the ball, which on one side is deep red, and on the other is uncoloured. So, here we could call the notion of ‘self’ deep red. Imagine the other side is deep green, the direct opposite of red, which we could call ‘other’. If we move across that coloured ball we move from a sense of self to a sense of other, with a muddy sort of brown colour in the middle where they are balanced. Thus one end of the self-other archetypal structure could be said to contain nothing of the other end. The same could apply to the structure-agency archetypal construct. The chapters in each of the following four sections of this book focus upon one pole, but as they are about real-life experience they would be located somewhere within the imaginary colour wheel in Figure 1.1. Bear in mind that this location is achieved by thinking of where they are less applicable, rather than where they should ‘be’. I have no desire to place them too firmly in one spot, thereby offering an oversimplified representation of a messy world.

Section 2. Exploring Self

This section focuses on the first of these poles, namely self. Although this can only be understood by what it is not (other), the chapters in this section are chosen as they focus more on self than on other. I start by questioning what is meant by ‘self’, and explore the notion of the emergent self, in which self is clarified through what one is not, and notions of self emerge from interaction with the other. This is done through negotiating entrance into a new group and trying to find out what that group stands for and what might be entailed by acceptance into the group. The way in which self is challenged and changed by other is discussed.

Chapter 8 questions the direction of t...