Up to the early 1990s, Japan was regarded as a role model of economic dynamism and equality. The World Bank (1993) praised it for spearheading the ‘East Asian miracle’ of high growth and successful economic development based on social equality. Japan was regarded as a prime example of shared growth in East Asia, in which a developmental state and business leaders not only activated workers for fast economic expansion, but in which economic and political elites were also prepared to share the fruits of this hard work with the general population. As part of developmentalism, Japan’s welfare state and social security programs were very small. Social inclusion and well-being of the population was not achieved through redistribution and social protection, but by high growth and fast increasing productivity. Researchers identified this developmental or productivist welfare state model as an additional type of welfare capitalism to Esping-Anderson’s ground-breaking typology of ‘Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism’ (1990) and as a common feature in fast developing economies in East Asia (Choi 2013; Holliday 2000; Kwon 2005). The result of Japan’s developmentalism and shared growth seemed impressive. Many comparative studies of the 1970s and 1980s suggested that Japan was an exemplary case of equality in opportunities and in outcome when compared to Western industrial societies (Boltho 1975; Bornschier 1988; Dore 1987; Galtung 1971; Reischauer 1977; Sawyer 1976; Vogel 1979). This view was also shared in Japan: for decades, it considered itself as not only an ethnically, but also a socially homogeneous society of economic equity and equal opportunity. The strong self-perception as a ‘general middle-class society’ (sōchūryū shakai) summed up this view of Japan as a society that rewarded personal effort and hard work with upward mobility and in which wealth and income were distributed fairly. From the 1970s onwards, this model of Japan became prescriptive as the ‘Japanese way of life’ (Chiavacci 2007: 41–45). Takehiko Kariya (1995: i) summarizes the ideal male life course of the salaryman (sararīman), a white-collar worker in a large corporation or public service, as follows:

Collapse of ‘general middle-class society’: The end of social upgrading

In the late 1980s, Japan appeared to be the realization of an ideal case of growth and equality. It not only seemed the leading goose of the Asian flock of fast industrializing economies, but was even regarded as a model case of equity and growth, which Western industrial countries should emulate (Dore 1987; Vogel 1979). This success story, however, came to a sudden end in the late 1990s, mainly due to two parallel developments.

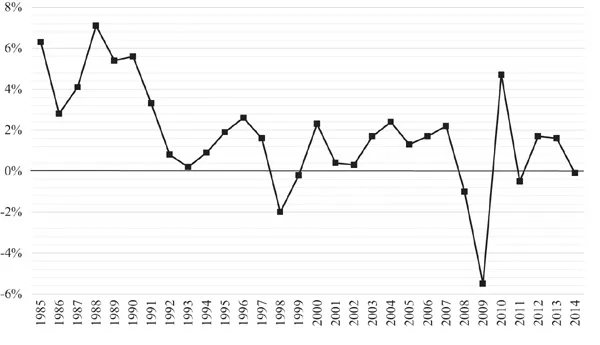

First, economic growth turned into economic stagnation. In the early 1990s, the burst of speculation bubbles in the stock and real estate markets led to a sudden economic downturn after the spectacular growth of the years before (Figure 1.1). Just as the Japanese economy seemed to have recovered from the burst of the bubble economy in the mid-1990s, a strong recession hit Japan, which was followed by poor growth up to 2002. The years from 1992 to 2002 came to be known as the ‘lost decade’ (ushinawareta jūnen) (Genda 2005: x). Japan, the former star of growth and economic dynamism, had turned into a problem case of stagnation.

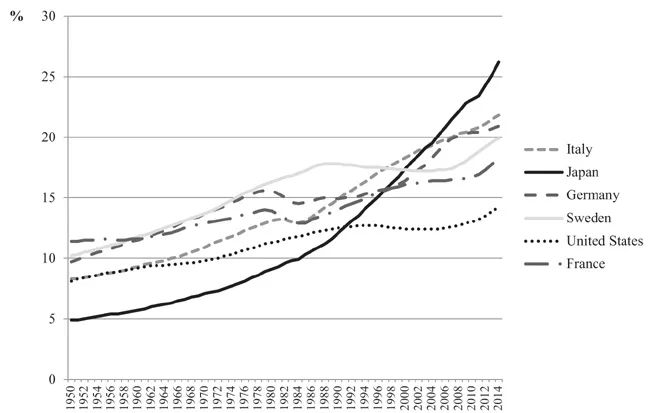

Second, a fundamental demographic change in Japan marked the 1990s. Japan turned into a demographically stagnating and hyper-ageing society (Coulmas et al. 2008). The success story of post-war economic growth had also, among other factors, been promoted by the demographic dividend of a young and expanding population. Japan’s proportion of elderly people aged 65 or older was among the lowest in fully industrialized societies in the late 1980s. However, due to Japan’s late and very fast demographic transition, the speed of ageing since 1970 has been much faster than in Western industrialized countries (OECD 2009). Over the short time span of about 15 years from the late 1980s to the mid-2000s, Japan converted from being the youngest advanced industrial society into being the demographically oldest society worldwide (Figure 1.2). During the same period, Japan’s overall population started to stagnate and its total fertility rate (TFR) continued to fall well below long-term reproduction (MIAC 1984–2015). Hence, during the so-called ‘lost decade’ of the 1990s, Japan was not only confronted with a fundamental economic slowdown, but also had to face a huge demographic challenge as its young, dynamic society was transformed into an old, stagnating one.

It was only in the late 1990s that these two fundamental structural transformations led to a re-evaluation of Japan’s assumed exceptional degree of equality. Mainly two studies triggered an academic and public debate on new and rising inequalities in Japan: economist Tachibanaki (1998) claimed a sharp increase in household income inequality between 1980 and 1992; sociologist Satō’s (2000) research on social mobility patterns described Japan’s transformation into a closed society in which status attainment depends more on social background than on individual achievement. Both studies were criticized on the grounds of the data used and methodological aspects (Hara and Seiyama 2005; Hashimoto 2001; Ōtake 2000; Seiyama 2000). Considering the complexity of the analysis of income data and the restrictions of intergenerational survey data, however, it is hard to pass judgment. In any case, the two works became best-sellers, leading to a broad discussion of ‘new’ disparities, the collapse of the meritocratic school system and the social role of elites, and prompting numerous publications on the topic – both scientific and journalistic (BSH 2000; CKH 2001; Hashimoto 2001; Kanomata 2001; Kariya 2001; Miyajima and RSSKK 2002) – some of which confirmed new and rising inequalities since the early 1990s and started to declare the end of Japan’s ‘general middle-class society’.

In fact, a number of empirical studies had already questioned the model of Japan as a ‘general middle-class society’ earlier (Azuma 1994; Higuchi 1994; Ishida 1993; Ishizaki 1983; Tachibanaki and Yagi 1994). Why, then, did the studies of Tachibanaki (1998) and Satō (2000) cause such a stir, while earlier studies had hardly been taken up in public debate? Their publication coincided with a new zeitgeist, which gained momentum in the context of reform debates and matched actual experiences of the middle classes in their lifeworld (Chiavacci 2008). The ‘golden years’ of economic expansion and fast growth had come to an abrupt end in the early 1990s, but it took several years for the experience to sink in. A short growth period in the mid-1990s seemed to indicate that Japan had quickly overcome the collapse of its bubble economy (Figure 1.1). In 1998, however, Japan’s economy fell back into a full recession and many countries in East Asia were hit by capital flight and a currency crisis. Not only Japan, as the leading goose, but the whole East Asian model seemed to be disintegrating.

At the same time, Japan’s demographic transformation gained new public attention. In 1997, revised population prognoses by Japan’s National Institute of Population and Social Security Research predicted that the stark decrease in Japan’s TFR of recent years was by no means a temporary phenomenon, but would, in fact, turn into a long-term trend (Schoppa 2006: 152–153). Not only hyper-ageing, but also very low birth rates and population decline had by now become undeniable facts. Quite suddenly, Japan had transformed from a seemingly unstoppable model of dynamism and growth into a country marked by long-term stagnation and decline.

While Japan’s and East Asia’s model of shared growth ran into a fundamental crisis, the US and its liberal economy returned to a path of economic growth, success and innovation after years of problems and decline. In view of these diametrical developments, influential pundits and important politicians in Japan called for structural reforms and deregulation à la US (Nakatani 1996; KSK 1999; Watanabe 2001). One central goal of these reform efforts was to overcome ‘bad equality’ (akubyōdō), which was identified as a hurdle to Japan’s comeback (Nakatani 1997: 400):

The Japanese must realize the need to replace the post-war emphasis on egalitarianism with a more balanced vision recognizing the importance of fair competition for the sake of increasing efficiency. That is, Japan cannot be efficient and remain competitive in the world market if it continues to be preoccupied with the equality of outcomes seen in the overemphasis on the distribution of income. Egalitarianism, which l...