![]()

1 Introduction

The Landscape Puzzle

In Berlin alone, according to Police information 100,000 people took part at the demonstration using the slogan: “Fukushima warns: shut down all nuclear power plants.” The organizers said it were the largest anti-nuclear protests in Germany ever.

Reuters Deutschland, March 26, 2011.

Anti-nuclear protesters have completed a 24-hour blockade of the entrance to Hinkley Point nuclear power station, marking the first anniversary of the disaster at the Fukushima power station in Japan. The Stop New Nuclear alliance hailed the rally as the “largest anti-nuclear protest in three decades” with up to 1,000 demonstrators surrounding the site on Saturday.

Belfast Telegraph, March 11, 2012.

Environmental organizations, the DUHA Movement and Greenpeace [Czech Republic], announced today that they are returning to radical forms of protest against nuclear energy... According to Machálek [Director of the DUHA Movement], the environmentalists were inspired by contemporary protests in Germany that included hundreds of thousands of participants: “We could not sit on our hands any more. We rely on the support of our numerous sympathizers...”

Deník Referendum, April 1, 2011.

If democracy is defined as the rule of people, then political participation is a necessary condition. Political participation is the core venue through which citizens exert their “rule” – it is how they communicate their preferences to political representatives and influence political decisions. The boom in participatory channels that are not related primarily to elections is one of the fundamental features of contemporary democracies (Dalton 2000; Dalton 2014; Inglehart 1997; Inglehart and Catterberg 2002; Meyer and Tarrow 1998; Norris 2002; Rosanvallon 2008; van Deth 2014). Whereas in the 1950s political participation was mostly limited to voting and electoral campaigning, today nonelectoral activities are also notably widespread. Sizeable numbers of people sign petitions and statements, contact political representatives via letters or emails, attend demonstrations, participate in marches, go to political meetings, attend public hearings, take part in political blockades and occupations, and use consumer behavior on a mass scale to make their political voice heard, by buying certain products, or explicitly refusing to buy others.

Commentators mostly welcome the rise of nonelectoral participation as a way to strengthen democracy. Citizens can be involved in politics between elections, and participate more directly and flexibly in issue-oriented politics (Dalton 2008, 93f; Inglehart 1997, 207; Rosanvallon 2008). National governments, the European Union (EU), and various foundations have embraced this rise in nonelectoral participation as a tool with which to improve contemporary democracies, and fight the democratic deficit present in different governance settings.1 They have implemented various projects and institutional innovations to increase citizens’ involvement in politics between elections.

Nonelectoral participation varies dramatically across countries. As the example above regarding protests related to the Fukushima nuclear disaster illustrates, countries differ widely in the numbers of politically active people: whereas around 100,000 people demonstrated against nuclear power in Berlin, approximately 1,000 did so in Britain; in the Czech Republic, two environmental organizations opposed to nuclear power threatened radical protests as an April Fool’s Day joke, but no petitions, protests, or campaigns related to the Fukushima disaster took place in the country. This wide variation in the volume of activism also applies to other famous worldwide campaigns. For instance, participation in demonstrations against the war in Iraq on February 15, 2003, varied from 300,000 people in Australia (2.5 percent of the population) to 60,000 people in Norway (1.3 percent of the population), and 20,000 in Hungary (0.2 percent of the population) (Verhulst 2010, 16f).

Of course, there is cross-country variation in the specific events that trigger nonelectoral participation, and in the topics and timing of participatory waves. In the 1990s the biggest mobilizations seemed to be the protests of the global justice movement; in 2003 mobilizations against the war in Iraq; and ten years later anti-austerity demonstrations filled the front pages of national newspapers. In addition, topics of nonelectoral activism probably differ across countries.2 For instance, whereas in Poland, Hungary, and France most nonelectoral collective activism addresses economic and social policy issues, Germany, the Netherlands and the Czech Republic mobilize mostly around issues such as human rights or the environment (Císař and Vráblíková 2015; Fillieule 1997; Kriesi et al. 1995, 22). Yet despite these differences in topics, there have been more or less persistent and large cross-country differences in the general volume of nonelectoral participation (Chapter 3 discusses this phenomenon in more detail). Thus the country landscape of political participation is crucial.

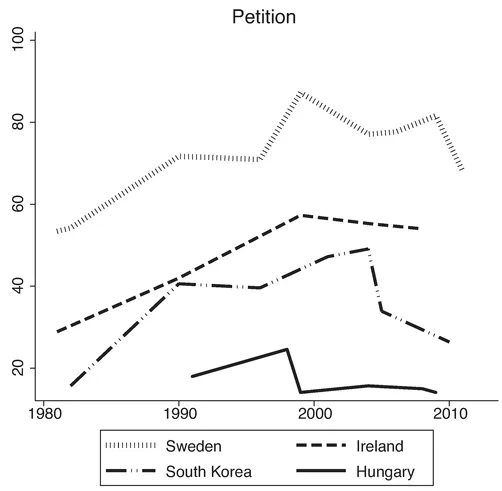

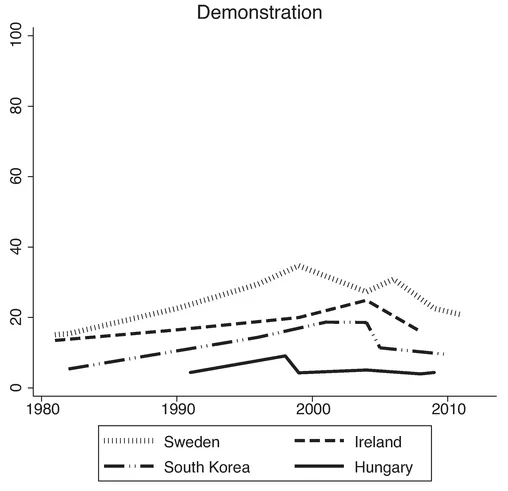

Figure 1.1 illustrates the changes over time in the proportion of the general population of four contemporary democracies with different participatory levels (Sweden, Ireland,3 South Korea, and Hungary) that reported having signed a petition and participated in a demonstration. Whereas most of the literature on nonelectoral participation celebrates the similar over-time trend in the data, which is undoubtedly interesting, I suggest a different reading of the numbers: there are huge cross-country differences that stay more or less stable over time. Although Sweden and other countries experienced an increase in the number of participants from the 1980s to 2000, Sweden always scores higher than the other countries in the sample. Similarly, the other countries fluctuate in the same order at all time points for both activities (Ireland, South Korea, then Hungary). Hungarians participate in petitions and demonstrations much less frequently than others, while Koreans do so a little bit more. The landscape character of nonelectoral participation seems to be the most important trend in this data. The largest within-country increase of 34 percent (Sweden’s participation in petition signing from 1981–99) is quite small, compared to the biggest cross-country gap of 73 percent between Sweden and Hungary in 1999. In fact, the gap in petition signing between Sweden and Hungary is consistently above 47 percent.

While virtually all comparative studies report large differences in nonelectoral participation across countries (Dalton 2014; Norris 2002, chap. 10; Teorell, Torcal, and Montero 2007), the standard literature pays little attention to these persistent differences. Instead, discussions about the over-time growth of nonelectoral activities, or the inequality in political activism, dominate the conventional debates. In contrast to these studies, this book focuses on the landscape of political participation between elections. It seeks to unravel the processes underlying this more or less persistent cross-country variation, and to show how and why people in some countries tend, systematically, to participate more in nonelectoral politics than people in other countries. This knowledge is highly relevant, given the generally shared aspiration to have a more active citizenry. Why is it that activism flourishes in Sweden, while in Hungary, after more than 20 years of democratic government, the levels are so low? What factors should we blame for that? What accounts for the strong cross-country differences in political participation? Is it a matter of immutable traits, or can something be done about it?

Challenging Conventional Wisdom

The vast majority of available wisdom does not help answer these questions. Specifically, there are three areas of literature that could potentially disentangle the landscape puzzle of nonelectoral participation: microlevel factors, voter turnout literature, and an inclusive-consensus perspective on democracy. However, none of them really does. For

Figure 1.1 Cross-country Differences in Political Activism over Time. Note: Figure shows percentage of people that answered that they “have actually done” the activity (signing a petition, or attending a lawful demonstration). Source: World Values Survey, European Values Study 1981–2013.

example, the general political participation literature, which focuses mostly on microlevel factors, does not pay in-depth attention to cross-country differences in nonelectoral participation. Debates in this field are dominated primarily by discussions about individual-level inequalities in political participation that emphasize individuals’ personal characteristics (Schlozman, Verba, and Brady 2012; Teorell, Sum, and Tobiasen 2007; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). Although the distribution of individual factors such as civic skills or resources may vary among countries, they most likely do not differ enough to completely account for all of the cross-country differences. Political participation researchers would probably not even suggest this explanation.

However, work developed in other disciplines, particularly in area studies, implies that microlevel factors might be responsible for the landscape variation in political activism. For instance, the literature on new East-Central European democracies suggests that the political passivity of citizens in post-communist countries originates from an aversion to participation caused by forced and involuntary participation during communism, and from their lack of the social capital and civic skills that people normally learn in democratic regimes (Barnes 2006; Bernhagen and Marsh 2007; Howard 2003; Inglehart and Catterberg 2002). Similarly, proponents of the “Asian values hypothesis” would argue that people living in Asian countries participate less in nonelectoral politics – which is highly individualized and often involves criticism and conflict – because they have typical “Asian” (collectivist, deferential, and consensus-oriented) values (Dalton and Ong 2005; Welzel 2011).

By contrast, this book will show that the cross-country gaps in nonelectoral participation do not originate primarily from citizens’ individual characteristics. Rather, the landscape character of political participation is a result of systemic characteristics of the countries where these people live. Whereas microlevel factors are necessary for political activism (especially for determining what types of people are more likely to participate), the overall context of a country’s political system is the most important factor underlying the cross-country differences in nonelectoral participation. The context of national political structures induces and constrains peoples’ political behavior, and citizens make their participatory choices according to the environment in which they live. In other words, the story of the participatory landscape is less about individual Hungarians, Koreans, or Swedes (as is suggested by some of the literature) and more about Hungary, Japan, and Sweden as such.

The idea that “context matters” is an essential notion of comparative politics. Classic studies recognized the importance of an individual’s social system context as a core research puzzle for comparative social sciences (Almond and Verba 1989; Lazarsfeld and Menzel 1965; Przeworski and Teune 1970). Przeworski and Teune explicitly acknowledge that “identification of the social system in which a given phenomenon occurs is a part of its explanation” (1970, 7). Similarly, Almond and Verba (1989) point out that micropolitics (individual behavior) can be explained by macro politics (characteristics of political systems). Lazarsfeld and Menzel (1965) describe the same idea when referring to members and their collectives.

The contextual perspective on individual citizen behavior is very well developed in the voter turnout literature (Blais 2006; Dalton and Anderson 2011; Jackman 1987; Jackman and Miller 1995; Norris 2002), which is the second-best way to find cues to help understand why people participate in nonelectoral politics differently across contemporary democracies. However, knowledge gained in this literature does not help us very much either. First of all, it is not theoretically plausible to expect nonelectoral participation to be affected by the same contextual determinants as voting. The contextual determinants of voting mostly include electoral laws that directly address only voting. Why should factors such as the magnitude of an electoral district affect signing a petition or boycotting, which have little to do with elections? The pioneering studies on national context and nonelectoral participation have also supported this point empirically. Generally, they conclude that nonelectoral activities are qualitatively different from voting, and call for further research that would “begin to explore the potential causal forces at play” (Weldon and Dalton 2014, 127; also Marien, Hooghe, and Quintelier 2010).

The third stream of research that could resolve the landscape puzzle of nonelectoral participation is much more promising. I call this group of literature the inclusive-consensus perspective on democratic regimes, and pay detailed attention to it in the book. Generally, these studies assert that inclusive and power-sharing democratic arrangements, based on trustful cooperation and consensus, facilitate people’s involvement in politics. This notion is generally accepted in political science and policymaking, and is present in a number of works on democratic theory, political systems, and political culture. Lijphart’s (1999) conception of consensus democracy, which attributes the positive effect of inclusive-consensual context to institutional decentralization, perhaps develops this approach to the greatest extent. Yet proponents of deliberative democracy, who seek consensus and inclusion in public discursive arenas or social capital theory (which emphasizes the role of collective trust, solidarity, and cooperation in the cultural domain of political systems), suggest a very similar mechanism. The theory of the benign effect of inclusive and cooperative political context on individual participation in nonelectoral politics has received little empirical inspection, and the available findings are rather mixed.4 However, the inclusive-consensus perspective is very compelling and widely accepted.

This book challenges the conventional perspective of the benign effect of inclusive consensus on political activism. In contrast, it argues that, in addition to inclusiveness, public contestation within the political system (rather than consensus) plays a crucial role in facilitating people’s participation in nonelectoral politics. Drawing on the literature that emphasizes the role of public contestation for democratic regimes, particularly Robert Dahl’s (1975) conceptualization of polyarchy, the book develops a theory of inclusive contestation that specifies how political competition, embedded in a Stat...