![]() PART I

PART I

Constructing the Popular![]()

Chapter 1

The Problem of Popularity: The Cancan Between the French and Digital Revolutions1

Clare Parfitt-Brown

Defining popular culture is a notoriously slippery business. British cultural studies theorist Stuart Hall writes, ‘I have almost as many problems with “popular” as I have with “culture”. When you put the two terms together, the difficulties can be pretty horrendous.’2 This complexity is at least partly due to the fact that, as John Storey, another cultural studies scholar, has pointed out, popular culture has meant different things to different people at different times.3 In Inventing Popular Culture, Storey explores a variety of nineteenth- and twentieth-century intellectual discourses about the popular. This chapter, however, is concerned with physical performances of the popular at different historical moments, contextualized in relation to the popular music that accompanied them, as well as wider political and social forces. My analysis focuses on a specific popular dance practice: the cancan. In considering what constitutes the cancan’s popularity I examine three particular moments in the dance’s history: the early cancan of the 1820s and 1830s performed by working-class dancers to quadrille music; the cancan at the Moulin Rouge of the 1890s performed by professional dancers to quadrilles played by the venue’s orchestra; and the cancan danced to pop music of the late twentieth century in Baz Luhrmann’s film Moulin Rouge! (2001). While much of the cancan’s history is necessarily excluded by this selection, it nevertheless allows a comparison of three periods during which the dance’s popularity was particularly visible. These snapshots reveal popularity as a distinctly malleable concept, in which various pasts, presents and futures are renegotiated in the moment of performance.

The Emergence of the Cancan: Deviations from Grace

The cancan emerged in working-class dance venues called guinguettes on the outskirts of Paris in the late 1820s. Guinguettes often had indoor and outdoor dance floors, and a small band of variable size consisting, for example, of a fiddle, clarinet, flageolet4 and tambour or drum to provide the rhythm for the dancers.5 The cancan was initially an improvised variation on the quadrille, a square dance performed in couples using steps influenced by ballet vocabulary and danced to rhythmic music in 2/4 or sometimes 6/8 time. Cancan improvisations often occurred in the final figure of the quadrille, danced to energetic music written for a galop. Throughout the nineteenth century these variations sometimes maintained the name ‘quadrille’, or even ‘contredanse’ from which the quadrille was derived, but dancers, writers and courtroom judges often used the terms ‘cancan’ and ‘chahut’ (uproar) to distinguish steps that deviated from the set figures, with the latter term designating wilder versions of the dance that broke social and legal codes of ‘public decency’ (the term ‘cancan’ will be used here to refer to both cancan and chahut variations, unless stated otherwise).6

The quadrille was danced by all classes,7 but the form of the dance disseminated in dance manuals embodied the values of the post-revolutionary bourgeoisie through graceful bodily deportment, classical alignment of the body, control of the outer limbs from the centre, limited body contact and an emphasis on the male-female couple. During the 1820s, the quadrille’s regular rhythm, composed for dancing rather than listening, and its simple walking steps, reduced in complexity from the intricate footwork of the contredanse française, led some bourgeois commentators to claim that the form had become uninteresting.8 By 1826, however, working-class dancers, mostly male but also occasionally female, began introducing improvised variations that subverted the bourgeois ideals of the quadrille’s set figures.9 For example, the movement of isolated body parts, such as the legs, disrupted centralized control of the limbs. The power of dancing masters to control the bodies of the public by teaching set choreographies was also overturned by placing value on individual improvisation. Paul Smith (a pseudonym for Désiré-Guillaume-Edouard Monnais), co-director of the Paris Opéra from 1839 to 1847, described these developments retrospectively in 1841, referring to the cancan as the contredanse:

Each dancer set about improvising a kind of mimed dialogue, with very lively expression. Instead of dancing quite simply, with the most elegance and grace possible, with straight head, arms close to the body, and without departing from the catalogue of classical steps – the assemblé, the six-sol, the entrechat – they invented feet movements, arm movements, head movements; they attacked the status quo by dancing from all sides at once…. In a word, here the contredanse is a dramatic form where each person improvises, following his or her flair, expressing his or her individuality.10

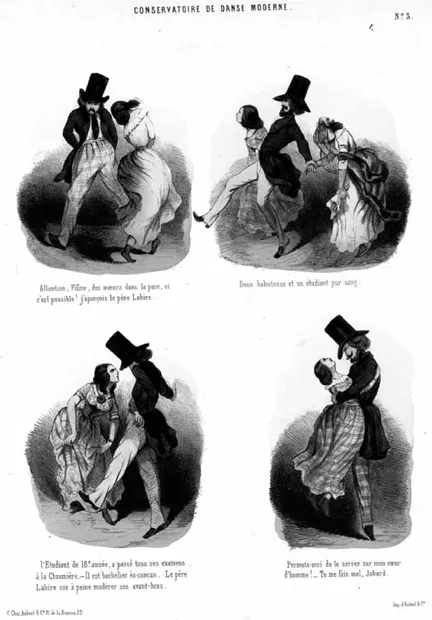

Some of these improvisatory possibilities are shown in a series of sketches of the cancan by Quillenbois (a pseudonym for Charles Marie de Sarcus) published in 1845 (Figure 1.1, below).

The cancan improvisations seem to have been influenced by a variety of foreign dance forms that the working classes would have seen performed at the popular theatres of the Boulevard du Temple. A number of contemporary sources cite the influence of the Spanish cachucha,11 performed by Spanish dance troupes touring France after 1825.12 Other dances linked with the cancan include the Spanish fandango,13 the Italian tarantella and saltarello,14 the Polish Cracovienne 15 and the Haitian chica.16 Foreign dance forms such as these appeared as exotic attractions in a wide range of popular theatrical productions in the first half of the nineteenth century, including romantic ballet-pantomimes and melodramas.17

These productions participated in the creation of what Petra Ten-Doesschate Chu describes as a new form of French popular culture built around the mass consumption of romantic historical literature and popular theatre.18 Not satisfied with consuming foreign dances as spectacles, working-class dancers incorporated them into their own movement vocabularies and used them as inspiration for their own innovations. Perhaps these suburban dancers had recognized an opportunity to fashion a new, popular dancing body that undermined the hierarchy of taste performed in the bourgeois quadrille. This working-class corporeal rebellion can be interpreted in terms of changing notions of popular power in the wake of the French Revolution and its uncanny repetition in the Revolution of 1830.

Figure 1.1 Illustrations by Quillenbois (Charles Marie de Sarcus) published in Le Conservatoire de la Danse Moderne (1845).

The Convulsive, Contagious Cancan: Symptom of Popular Liberalism

When the cancan emerged in France in the late 1820s, economic depression and the gradual limitation of personal liberties under the conservative monarchy of Charles X (1824-30) fuelled calls for a return to the liberal rhetoric of the French Revolution of 1789.19 Historian Roger Magraw argues that dissatisfied members of the bourgeoisie used the emerging liberal press to fan the flames of working-class unrest in an attempt to recruit workers as foot soldiers in a revolt against the Restoration Monarchy (1815-30).20 The mobilized urban working classes took to the streets in July 1830 and overthrew the Bourbon Monarchy, only to find themselves subject to a new regime, the July Monarchy of King Louis-Philippe (1830-48). The new king aligned himself not with ‘the people’, but with the bourgeoisie, aiming, he claimed, ‘to remain in a juste milieu, in an equal distance from the excesses of popular power and the abuses of royal power’.21 According to Magraw, this precipitated, ‘several years of popular disturbances, peaking in August 1830 and early 1832, in which workers and peasants tested the ability, and discovered the unwillingness, of the new regime to satisfy their grievances’.22 These events gave the notion of ‘the popular’ a specific inflection; ‘the people’ were members of the working classes and petite bourgeoisie whose violent political power had been proven in 1789, but who remained disenfranchised. Popular culture therefore evoked the latent revolutionary potential of the masses, simmering beneath the surface of French society.

The cancan emerged in this volatile atmosphere of an incipient working-class consciousness enflamed by bourgeois and bohemian romantic political idealism. For many of those removed from working-class concerns, the body politic performed in the cancan was a dystopia. Louis Désiré Véron, director of the Paris Opéra from 1831 to 1835, wrote in his memoirs of 1856:

After 1830 people’s hearts took a long time to beat at a normal rhythm … Schoolchildren and the common people as one indulged in a bizarre, imaginative thrust to transform the way the French danced; out went the gradually developed, rounded and elegant movements of our forefathers, in came a frenetic, convulsive dance, indecent and respecting no-one, which became known appropriately enough as the chahut and which even gave birth to a new verb chahuter[to muck around].23

Véron portrays the cancan as a physical symptom of a disease that had infected the bodies of ‘common people’ during the revolution. This pathological model of the cancan resonates with the biological theories of historical regression that emerged in France in the wake of 1789, and were reinforced by each return to revolution in the nineteenth century. In the theory of degeneration, the lurching of French history between revolution, republic and monarchy was attributed to a hereditary disease in the bodies of its citizens and in the body of the French nation as a whole.24 Later in the century, the historian Hippolyte Taine (1828-93) would identify this disease as popular liberalism, allowed to spread by France’s gradual expansion of the electoral franchise.25 For Véron, the cancan was a bodily expression of the pathological historical convulsions of French society, spread by contagious popular liberal attitudes.

As a symptom of social and physical disease, the cancan dancer’s body quickly became a site for the reassertion of control and order over the national body politic by the French authorities. From at least 1829, inspectors policed the public balls,26 charged with ‘see[ing] that no indecent dance is practised there, such as the chahut, the cancan, etc.’.27 Gasnault counts about 40 reports of trials for indecent dancing in the Gazette des tribunaux between 1829 and 1841, without a single acquittal, although he suspects that this may be a modest sample of the trials that actually took place.28 The punishment for ind...