![]()

Chapter 1

Ruins and Imperial Legacies:

Global Geographies of

Portuguese-built Forts

Are academics located in the West, or working in Western conceptual and narrative paradigms, incapable of opening up the perspectives within which we can view the non-Western world? Or have they adopted reactive perspectives which lock them into a reductive position whereby they can return the colonial gaze only by mimicking its ideological imperatives and intellectual procedures?

Ania Loomba (1998: 256)

Never does one open the discussion by coming right to the heart of the matter … to allow it to emerge, people approach it indirectly by postponing until it matures, by letting it come when it is ready to come. There is no catching, no pushing, no directing, no breaking through, no need for a linear progression which gives the comforting illusion that one knows where one goes.

Trinh T. Minh-ha (1989: 1)

Decadence begins when a civilization falls in love with its ruins.

Derek Walcott (1964: 3)

Doing Cultural Geography

Over 20 years ago, Pierre Nora (1989) argued that in the modern period not only was there a decline of ‘real environments of memory’ (milieux de mémoire), that permanently and organically recreated the past, but there was also the emergence of sites of memory (lieux de mémoire), that is, specific places where both formal and popular memories are produced, negotiated and take root. In these lieux, the material, symbolic and functional coexist, creating mixed, hybrid and fluid atmospheres. Partly following on these concerns and processes – the ways in which memory attaches itself to places – a growing number of cultural geographers (together with academics from fields such as anthropology, film studies, history, literature, sociology, and others) have been attempting to understand how heritage, seen not as a single story, but as plural versions of the past socially constructed in the present (Lowenthal 1998), and heritage sites, are increasingly mobilised as important cultural, political and economic resources in our contemporary world (Graham 2002).

Cultural geographers have extended this agenda by exposing, undermining and complicating simplistic readings of places and their pasts (Atkinson 2005), connecting these to wider transnational spatial processes, and questioning significant geographical categories of belonging and difference. Turnbridge and Ashworth (1996), for example, have focused on heritage sites as nodes where ‘dissonant heritages’ of different social groups collide, and explored the possibilities of a more inclusive and plural heritage in multicultural societies (see also Graham, Ashworth and Turnbridge 2000 on this large and growing literature). Johnson (2003) examined the articulation of remembrance, and the ambiguity between remembrance and forgetting, in the context of the political and cultural turmoil of Ireland post-WWII (see also Heffernan 1995 and Withers 1996 on monuments dedicated to nationalism and war). As an alternative to the fixed explanations of formal heritage, Crang (1994 and 1996) examined popular expressions of social memory by looking at the ways in which individuals and groups engage and articulate their senses of heritage through everyday artefacts and ephemeral materials such as photographs and postcards. Edensor (2005), looking at industrial heritage ruins in the west, argued for a destabilisation of the notion of ruins as signs of dereliction and waste, a notion constructed upon aesthetic judgements which widely differ from the tradition of attributing celebratory accounts to non-industrial ruins. Contrasting with mainstream ideas, Edensor is concerned with the possibilities, effects and experiences which ruins can provide, reclaiming industrial ruins from negative depiction.

At the same time, in the past decades, cultural geographers have been significantly influenced by developments in postcolonial theory and practice (Pratt 1992; Blunt and McEwan 2002; Nash 2002; Blunt 2005; Sharp 2009; Yeoh 2009). Inspired by early works of Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire and Léopold Senghor, among others, which attempted to bring anti-colonialism and ideas about African unity to a global audience, and by Edward Said’s Orientalism, Homi Bhabha’s hybrid and ambivalent identities and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s work with the Subaltern Studies Group, cultural geographers have joined some of the postcolonial turn concerns. Postcolonial theory can be understood as ‘… a theoretical resistance to the mystifying amnesia of the colonial aftermath’ that insists upon revisiting, remembering and interrogating the colonial past (Gandhi 1998: 4), and most usefully, it embraces a variety of critical perspectives on the diverse histories and geographies of colonial discourses, practices, impacts, and their legacies in the present (Nash 2002). As Ryan (2004: 470) argues, ‘the interest in postcolonialism marks one of the more striking ways in which cultural geographers (and indeed human geographers more generally) have been concerned to respond to major intellectual and theoretical currents within the social sciences and humanities in the last two or three decades’. Thus, many cultural geographers have been examining the complex topographies of memory and forgetting on which colonialism depended and which postcolonial nations have inherited.

Cultural geography and postcolonialism have been criticised along similar lines. On the one hand there has been an apprehension about cultural geography’s ‘preoccupation with immaterial cultural processes, with the constitution of intersubjective meaning systems, with the play of identity politics through the less-than-tangible, often-fleeting spaces of texts, signs, symbols, psyches, desires, fears and imaginings’ (Philo 2000: 33). On the other hand there are concerns regarding the neglect of the material processes ‘which are the stuff of everyday social practices, relations and struggles, and which underpin social group formation, the constitution of social systems and social structures, and the social dynamics of inclusion and exclusion’ (Philo 2000: 37).

This book, encouraged by the new debates that the postcolonial turn promoted concerning questions of ‘geography, colonialism and postcolonialism’ (Power, Mohan and Mercer 2006: 231), takes a critical look at this evolving situation. I am concerned with material heritage, with ‘dissect[ing] post-colonialism as threaded through real spaces, built forms and the material substance of everyday biospheres’ (Yeoh 2009: 562), and involved in the re-materialisation proposals that emerged in Cultural Geography in the past years (Driver 1996). But I also attempt to offer an alternative approach to free heritage from its own confines of monumental materiality, by emphasising the particular kinds of social and cultural relationships that are established among different users of a heritage site. Whereas it is long recognised that historical sites as public monuments are critical places which capture and help to constitute individual and collective meaning (Barthes 1957), increasing attention should be paid to the spatiality of public monuments, where the sites are not merely the material backdrop from which a story is told, but the spaces themselves constitute the meaning by becoming both a physical location and a sight-line of interpretation (Johnson 1995). Material heritage sites should no longer be viewed merely as innocent aesthetic embellishments of the public sphere, but instead attention should be placed on their contextual spatiality.

Although today even more insidious and totalising forms of colonialism are at work (Venn 2006), there is a varied degree of continuity and discontinuity between colonial relationships and structures of power and privilege in the past and present. The ‘post’ in postcolonial does not signal the end of colonialism nor the stationary reproduction of the colonial in the present (Yeoh 2009), but, as Nash (2002) puts it, the ‘post’ represents the mutated, impure and unsettling legacies of colonialism, signaling also an emancipator project (Venn 2006). It is the continuation, although in transformed ways, of the forces that established the Western form of colonialism and imperialism, that constitute what Mbembe (2001) names the Postcolony. Thus, postcolonial nations are challenging places to think about the cultural geographies of memory, as the historical experience has created disruptive landscapes in which to consider the relationships between public memory, the production of knowledge and cultural self-definition.

Ruins and Legacies

For more than 500 years (1415–1974), during the Age of Discovery and colonialism, the Portuguese built or adapted fortifications along the coasts of Africa, Asia and South America. While these Forts were constructed under the aegis of one European power, with the profound global political changes of the nineteenth and especially the twentieth centuries, they are presently located in the political boundaries of at least 25 independent states, 1 all in the Global South. At a macro scale, mapping these buildings reveals a gigantic territorial and colonial project. While deeply connected at the start with the re-conquest of Iberian medieval kingdoms and with dreams of a unified Christendom that could subdue Islam in a multi-pronged conflict, these Forts became part of a network of power, acting as junctions between the colonial and the metropolitan in a particular system of governance. They also functioned as nodes in a mercantile empire, shaping early forms of capitalism, transforming the global political economy, and generating a flood of images and ideas on an unprecedented scale. The goal was to penetrate the commercial networks of Africa and gain control over the gold trade from Sudan. To a large degree, following Grosfoguel’s (2007) argument in relation to ‘what arrived’ in fifteenth-century America, Forts were an integral part of the entangled global hierarchies (European, capitalist, patriarchal, military, Christian, white, heterosexual, male) that were imposed on arrival. Yet, as Davidson (2001: 172) argues in relation to sixteenth century West Africa Forts and castles, from an African point of view they were merely of local importance, since what mattered to coastal Africans was not ‘these minor European ventures’ but the major pressures of powerful states of the inland country.

Today, these audacious architectural forms can be understood as active material legacies of empire that represent promises, dangers and possibilities, which are deeply understudied by academics, including geographers. It seems clear then, that as a global imperial system and a c1omplex of postcolonial legacies shaped by local and diverse political contingencies, this network of fortifications presents critical opportunities to construct a cultural and political geography that can inform our understandings of the ‘colonial present’. Post-colonialism, memory and amnesia, celebration and forgetfulness, contact zones, cultures of travel, dominance, governance, resistance, etc., are some of the concepts that are travelled through in this book.

Although my attempt is to participate in the contemporary understanding of the meaning of these Forts, I cannot claim a radical and alternative knowledge and a history and geography ‘from below’, since to a large degree this is a study about the subaltern and not a study with and from a subaltern perspective. Yet, while recognising the situated position of my knowledge (Haraway 1988), I understand this work as a contribution to a deeper and needed decolonisation of the Forts.

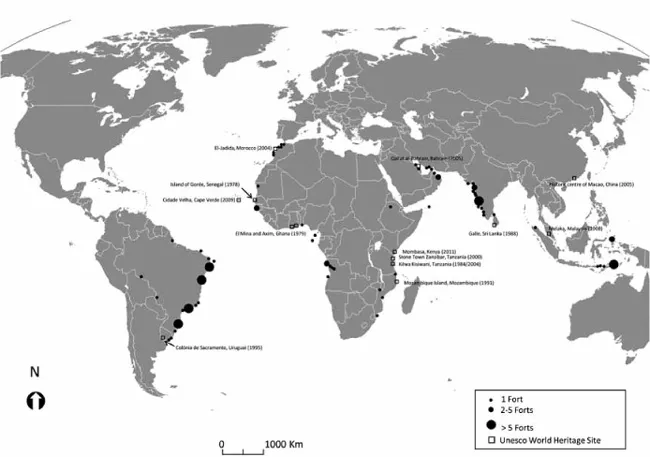

Mirroring the spatiality of the Portuguese imperial project until the second half of the twentieth century, Map 1.1 illustrates a predominantly coastal geography. To a certain degree this representation is deceptive and not only ignores flows, fluxes and changes, but does not do justice to the spatial processes that defined imaginary borders and territorialised the unknown. There are nonetheless some remarkable exceptions to the prominence of coastal sites: Massangano (on the UNESCO tentative list of since 1996), Muxima and Cambambe (both in ruins) in the Cuanza high plateaux and valley, Angola; the Forts along the Amazon river in Brazil, as far as the border with Peru (for the most part disappeared: see Dias 2008); the eighteenth-century Forts along the later established western border of Brazil; the Fort St Tiago Maior in the Zambezi river, Mozambique; and various Forts on the border of the state of Goa (prior to 1961 part of Portuguese India), India. When the empire was threatened in the nineteenth century, and also when it started to collapse in the twentieth century (see Sidaway and Power 2005), other fortifications were built inland, mainly in Guinea Bissau, Angola and Mozambique (Lobo 1989).

The immensity and remoteness of the newly encountered spaces required fortifications to be (deceptively) self-sufficient (Lemos 1989), creating a discontinuous geography of micro settlements of varying sizes and degrees of isolation, an archipelago of empire. However independent, the centralising and surveillant power from Lisbon meant that people, reports, plans, instructions, etc., travelled back and forth, constructing a dense network of knowledge. Archival material related to the reconstruction of Fort São Sebastião, in São Tomé, reveals, even in the twentieth century, the anxieties of builders in relation to the long months of wait before the architect in Portugal made decisions regarding issues such as use of materials, colours, and so on. The Forts were utterly international is their architectural, engineering and even social aspects. Nothing from local arts was incorporated on the projects or on the buildings. The construction masters were people that worked in Portugal, and only occasionally travelled to the construction sites. In many cases even materials like stones were taken from Europe. Muslim art for example did not attract any attention (see Dias 2008a). Despite this centrality and authoritarianism, from Macao to São Paulo there were also colonial communities that were small and dynamic republics (Cortesão in Curto 2007: 314).

Map 1.1 Portuguese-built Forts: a global geography

Lisbon scrupulously determined the guidelines for the Forts’ location: the existence of a good port, preferably in a naturally fortified location (island or promontory), a salubrious place (avoiding swamps or bogs) adequate for commercial activities, and the existence of a fresh water source difficult to sabotage (Teixeira 2008: 159). Thus, despite some remarkable exceptions, explained by different geopolitical agendas, the preferred location of Forts was on coastal islands: i.e. Mozambique Island and Sofala, Mozambique; Kilwa Kisiwani, Tanzania; Mombasa, Kenya. In fact, the Portuguese spatial model of colonising the inhabited Atlantic islands consisted on an offshore Fort that would supply Forts on the mainland (Bethencourt 2007). That was the case of Madeira and North African Forts, Cape Verde and the Guinea’s rivers Forts and São Tomé and the Gulf of Guinea Forts. When Socotra (presently Yemen) was conquered, there was an (failed) attempt to export this model to the Indian Ocean (Bethencourt 2007).

At times, maintaining a military force on inhabited islands was unsustainable, such as in Fernando Pó (presently Bioko, in Equatorial Guinea) or Socotra – as they presented serious challenges to control population. Seashores could also be artificially transformed into islands by opening a moat, such as in Galle (Sri Lanka), Cannanor or Cochim (India). If seashores were impractical, estuaries and marshes like Baçaim and Chaul (India) or Triquimale (Sri Lanka), and headlands like Muscat (Oman), Malacca (Malaysia) or Ternate (Indonesia), were chosen.

A brief look into the shifting control of this complex of Forts illustrates the colonial entanglements and the nuanced and ephemeral reality of imperial endeavours as Forts changed hands between Dutch, French, British, Spanish, Omani, Moroccan, and other local and regional kingdoms. Some Forts were lost even when their construction was not finished (which often started by building a provisional wooden fortification); and others changed hands consecutively (nine times in Mombasa). Remarkably, two served as royal gifts: Tangiers and Bombay were offered to England in 1661 as a dowry gift for the marriage of Princess Catarina of Braganza with Prince Charles II. This rich history of diplomacy, enterprise and resistance is visible and imprinted in the combination and overlapping of many architectural styles and construction techniques, reflecting the hybrid nature of these landmarks’ heritage (i.e. Galle) and the relentless changes that took place.

According to Bethencourt (1998: 404), the Portuguese built 244 Forts from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century, from which six were located in Cape Verde, 15 in the West African Coast and 20 in the East African Coast and Persian Gulf. Smaller Forts, an uncountable number of these have simply disappeared. In Brazil, from an estimated number of 450 historic defensive buildings, only 109 are known and 40 are legally protected. Many of these Forts the central pieces in complex networks of defence buildings which no longer exist, while others had an important role in the layout of towns and cities (i.e. Chaul, Bassein [north Mumbai] and Daman in India); some were encircled and embedded in the urban fabric (Fortaleza and Macapá in Brazil) or ended up supplying stone for various buildings (Colombo is a remarkable example, and what little is known of the Fort’s formation results from the limited interpretations of Dutch iconography); and many were simply engulfed by tropical forests and left to decompose.

Whereas earlier Forts or castles were still medieval, advances in artillery required Forts to be built in a transitional style, lowering towers, reinforcing walls and introducing changes to support heavy weapons (Moreira 1989a). During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries there was a tremendous renovation of many Forts (no longer castles), an effort that represented a phase of absolute belligerent engagement on a global scale, a rehabilitation of colonialism, a signature of mercantilism, and above all a step in the transformation from adventurist colonialism to capitalist imperialism. Yet one of the more critical transformations in these buildings’ tangible and intangible dimensions is connected to the transition brought by the ‘winds of change’ that blew through Africa and Asia especially in the second half of the twentieth century (early nineteenth century in South America). To various degrees these ruins and imperial legacies articulated the postcolonial status of various nations. Official and popular attitudes towards heritage varied and obviously changed with time after the emotionally charged spirit of the immediate post-independence periods. One of the present challenges for geographers is to attempt to understand who controls the Forts and their meanings, and what roles do different groups have in the maintenance and development of the sites. This network of Forts can contribute to our understanding of the manner in which postcolonial states resolve the ambiguous relationship with their heritage, the public treatment of colonialism in contemporary postcolonial states as well as the present in public memory.

Forts can be understood as marks and wounds of the history of human violence, but also as timely reminders that buildings never last forever, highlighting the fluidity of the material world. They are palimpsests. Some may comprise no more than empty shells of debatable authenticity, but derive their importance from the ideas and values that are projected on or through them. Many are open to visitors in a range of museums, from military history to culture and ethnography. UNESCO has classified 13 of these Forts as World Heritage Sites (WHS): one (Kilwa Kisiwani in Tanzania) has been on the danger list since 2004, and illustrating the power and politics of UNESCO procedures, actions and classification (see Boniface 2001), none is located in Brazil. Part of an imagined community, WHS are powerful symbolic markers of international cultural politics carrying with them promises of economic benefits. Significantly, in their postcolonial after-life, some of the Forts that represent this history of colonial expansion and struggle are now government buildings or official residences of high figures of state: i.e. Fort Dona Paula or Cabo Palace is the residence of the Governor of Goa, India; Fort Sohar (Oman), is a government building and since 1993 it has housed a history museum. Forts Jalali, Mirani and Mutrah, in Muscat, Oman (all thoroughly rebuilt by the Portuguese in the late sixteenth century) are presently in good condition, but closed to the public. The former, used as a prison and later as the official residence of the Oman Sultan, is currently a museum of Omani heritage and culture for visiting heads of state and royalty.

Among all inland Forts in Brazil, only Fort Coimbra participated in military action (1801 and 1864–70). Nowadays, Fort Príncipe da Beira, 3,000 km from the coast, is home to 58 soldiers whose everyday practice is patrolling the border with Bolivia. By contrast, Fort Nossa Senhora da Vitória (built in 1507 and renamed Nossa Senhora da Conceição in 1515), located in Hormuz Island, Iran, has retained its key geopolitical importance, as 90 per cent of all Persian Gulf oil leaving the region on tankers passes on this narrow waterway. Achieving an understanding between the Iranian and the Portuguese autho...