![]()

1

Deciphering Hybrid Organizations

What Are Hybrid Organizations?

In 2012, Nardia Haigh and Andrew J. Hoffman (2012) wrote in the journal Organization Dynamics that the market had shifted, and a new kind of organization had emerged: the hybrid organization. These organizations, they foresaw, had the fortune of being more suitable to effect a ‘positive social and environmental change’ (Haigh and Hoffman, 2012, p. 126). Hybrid organizations’ business models blur the boundary between for-profit and non-profit models taking the best of both worlds, Haigh and Hoffman argued, because they have adopted the visions and missions of the non-profit model and they can make a business with an income and sometimes even a good profit out of it. Typically hybrid organizations address social and environmental issues while selling goods and services that benefit these issues, such as fair-trade goods, ecological goods, social entrepreneurship in banking services, or public services such as water, waste electricity, transportation and similarly. Hybrid organizations are, according to Haigh and Hoffman, often driven by visionary entrepreneurs who value a healthy life, social justice and ecological sustainability, and many business owners are often less interested in creating a wealthy profit for greedy stockholders but more interested in making the business financially sustainable in order to continue this mission into the future.

Hybrid organizations exist in many diverse forms, although with similar business philosophies. The philosophy of water companies is based on a licence they have been given from society, which is based on an external mandate to fulfil certain duties in society. This mandate gives them a privileged space in the market allowing them to invest in long-term investments and prioritize on a long-term basis because they do not risk going bankrupt due to the natural monopoly they, in practice, have. This mandate must balance the external political pressures with internal interests and structures, which suits the hybrid organizational form well.

The case studies of water companies reflecting this licence strategy includes water companies from four different nations: Denmark, the UK, the US and South Africa. These nations are chosen specifically because they reflect a similar institutional legislative structure, which is a part of the global New Public Management (NPM) trajectory,1 while at the same time having different sustainability drivers reflecting their national, cultural and historical boundaries.

Water Companies

The water companies examined in this book have at least two main distinct functions:2 1) abstraction, purification and distribution of fresh water to the public and 2) transportation and purification3 of wastewater from the public. Abstraction of water means collecting the water from the natural resource. In Denmark all freshwater stems from groundwater deposits. In general the Danish groundwater is free of contaminants, which means that it is available for distribution almost without any processing (Andersen et al., 2006). This is not a typical setting in other countries. Groundwater deposits may be depleted and polluted, which means that purification of fresh water is needed before distribution to the public, no matter which source the raw water is abstracted from (Gray, 2010).

Processing fresh water prior to distribution consists of different techniques due to the purity of the raw water abstracted. In Denmark uncontaminated fresh water is only processed through two steps: 1) a sand and gravel filter to detach iron particles from it (ochre) mainly to create a good taste (and not a taste of iron), and 2) an oxidation process in order to re-oxygenate it and make it taste good (Karlby and Sørensen, 1998). In many other nations, additional processing is needed before the fresh water is ready for distribution. A typical process to eliminate bacteria and other contaminants is to add a chlorine solvent in order to reduce health-related risks of drinking freshwater or to process it with ultraviolet (UV) filtration. These processes eliminate any organic toxification in the raw water. Both types of processes affect the taste of water eventually: the water either tastes of chlorine or it tastes ‘boiled’ (Gray, 2010).

Water and wastewater is distributed and transported through networks of pipelines, storage basins and pressure systems to either reach or leave the consumers. Water is typically distributed by pressure systems in order to provide running water in the taps at a certain pressure. Wastewater transportation typically consist of two distinct but combined techniques: 1) a gravitation system, where wastewater is transported due to the force of gravitation which saves a lot of energy and 2) pumping systems, where wastewater is pumped from A to B (Karlby and Sørensen, 1998).

There are many different ways to process the purification of wastewater. Different methods are preferred according to the condition of the wastewater, which may locally differ even in the same city. The typical overall processing consists of a separation of fluids, lipids and hard materials through a grating process followed by a sedimentation process. After this different biological procedures follow in a flow of a combination of aerobe, anaerobe and sedimentation processes. These processes respectively detach nitrogen, phosphorus, ammonium, and derived or combined chemical compounds, and pre-sediment sludge for reprocessing of biological process water. Finally, chemical processes detach the remaining contaminants that the biological part could not process. Parallel to the fluid process, a sludge process is running to dewater the sludge to a level where it can be utilized either for energy making (biofuel) or as a fertilizer for farmlands (see Tchobanoglous et al. (2003) for a more in-depth description).

The above provides a brief description of the main processes water companies undertake. Besides these operations, renewal and maintenance of the infrastructure of pipe systems, pumping stations, basins and reservoirs as well as buildings and processing assets are also parts of the companies’ work. Most of the water companies’ investments are made in this part of the business, and it is typically here that the implementation of sustainability strategies are made. These need to be continuously improved because this is where most parts of the investments are outsourced to external parties such as constructors, contractors, consultants and suppliers, which are not directly involved in the daily operations and strategizing of the water companies.

Contractors, who have won a tender in competition with other constructing companies, will typically do the best job in creating a business for themselves. This means that the water companies must encompass their sustainability objectives into concrete and measureable performances stated clearly in the contracts with its suppliers. This part is often harder to enact in practice than the daily operations of a water company, where managers continuously oversee their workers. Disagreements between a water company and a contractor may end in court trials, where proofs of intentionality and performances are hard to settle afterwards. Thus, to exercise sustainable governance in the supply chain of the water company means spending extra resources and money to guarantee that external parties act sustainably on behalf of the water company. This is not an act that water companies necessarily enact smarter than any other business. Managers are urged to prepare contracts that state more accurately what they expect from their supply chain in order to lower their risks of unwanted and unsustainable external behaviours and to lower their economic expenses related to this.

Although the above encompasses most of the work a water company carries out, the brief description of this part of the work does not leave a full impression of how much work is actually entailed. The processing is run almost automatically by computers and machines (mainly pumps) in a water company, whereas the work of the people is concerned with operation, maintenance, renewal, rehabilitation, creating new pipeline systems and administration (Lenton and Muller, 2009), which is beyond the scope of this book.

The Legislative Context: New Public Management (NPM)

My study of the water sector gained relevance in Denmark when a Danish ministerial report in 2003 announced that a major institutional change was underway (Spenner and Wacker, 2003). A thorough service investigation of the Danish water sector was announced in order for the Ministry of the Environment and the Competition Authority to find ways and potentials for making the sector more efficient and effective, which could inform the governing state politicians in making decisions for an institutional change. Although the report was free of reference to international movements such as NPM, and no intergovernmental bodies such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) were mentioned in this report, it was clear that this was not an invention manufactured by the Danish state. These tendencies were part of a worldwide policy introduced by the OECD (Torfing, 2008; Greve, 2009). Through this it was introduced to the Danish water sector also. To understand what was going on in the Danish water sector as a result of the Structural Reform in 2007 it is necessary to understand this movement and its implications.

New Public Management or NPM is an umbrella term for a global movement consisting of neoliberalistic economic ideas initiated in the 1930s. These ideas gained political momentum in the late 1980s through prominent figures such as Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan (see Hood, 1991, 1998; Osborne and Gaebler, 1992; Lynn, 2006). Neoliberalism arose after the Great Depression as an academic discussion of how to prevent a similar situation from happening again. Figures such as Milton Friedman, Frederick von Hayek and Joseph Schumpeter were among those who, in the Post-War period, led a discussion as to how to connect economic theories with theories of democracy into a new synthesis of individual freedom away from the totalitarian regimes seen during the World Wars (O.K. Pedersen, 2011).

In the neoliberalist approach people (or agents, as they are referred to) are perceived as utility maximizing for their own sakes. Theories such as rational choice and agency theory were established to explain how people first and foremost were characterized by rational, but egoistic, thinking for their own benefit before others’, and how to cope with these negative traits. Theories of the market as an equilibrating system grew, emphasizing a system of freedom and competitiveness. Agency theories were developed to combine this with systems of fair, political control, such as principal–agent relations, contract-establishments, monetarism, and other rational behavioural theories. Ove Kai Pedersen explains this movement as:

While post-war international economies were built upon states’ objectives of national protection of ‘domestic markets’ and national welfare-states’ compensation for their workforce, today’s international competition rests on assumptions regarding that nations compete through opening their economies and mobilizing their material and immaterial resources in competition with others. (O. K. Pedersen, 2011, pp. 31–2, my translation)

These neoliberal ideas laid the foundation for the political lines of thinking that characterized NPM from the 1980s forward. It is debatable as to whether it today, after 20–30 years of implementation, still should be termed NPM rather than Post-NPM, Public Governance or just Public Management. I have chosen to continue naming it NPM as many of the initial ideas and instruments within the international trajectory of NPM are new to the water sector. The instruments used in this sector are derived from both the first and second international waves of NPM from, respectively, the 1990s and 2000s.

The first wave of NPM changes in the public sector was inspired by neoliberal economic ideas to minimize and streamline the public sector. Managerial instruments and techniques from the private business sphere were introduced in order for governments to save money and create more welfare through privatization (Hood, 1991). This idea was explained in the New Right policy movement adopted by the Niskanen-inspired Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. It was taken up in the Anglo-Saxon and American public administrations in the late 1980s as a reaction to the financial crisis in the 1970s and the following massive inflations that had stalled the global economy in many countries (Niskanen, 1973; Kettl, 2002; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011).

One of the first nations to implement this change was New Zealand, who faced had already faced an economic collapse in 1984. The experiences from stabilizing this nation’s economy formed what came to be international reform strategies induced by the OECD and diffused to many other nations known as NPM (Pallot, 1998; de Vries, 2011). The overall idea behind NPM was to save money by improving performance in the public sector, or to do more with less to prepare nations for the global competitiveness that governments faced (O.K. Pedersen, 2011).

Instruments to improve the Three Es; economy, efficiency and effectiveness in the public sector were soon adopted from the private business sector (Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2004; Christensen and Lægreid, 2010; J.S. Pedersen, 2010). These included budgeting and accounting, Total Quality Management, benchmarking, performance auditing, LEAN management, outsourcing and privatization. Some countries suffered severely from financial depletion, and this strategy proved to have the effect of stabilizing national economies, such as in New Zealand (see Whitcombe, 2008). However, not all instruments made it possible to do more with less.

The quality of public service – privatized or not – did not improve everywhere. Rather it created a new massive bureaucracy which only counted quantitatively how many were serviced – not how well they were serviced. Especially in the human relation part of public services such as hospitals, nursing homes, childcare and schools, sending more individuals through the system with fewer personnel did not improve the quality that the citizens experienced (see Gustafsson and Szebehely, 2009). To count the quality performed in quantitative measurements through performance auditing was also hard to do in Denmark. For instance, many newspapers wrote about relatives of the elderly and children who felt it rather inhuman that their relatives were only looked after by a nurse for 15 minutes per day.

The second wave of NPM was initiated in the late 1990s and tried to improve the quality of public service in new ways by moving away from the rigid counting of quantities. Instead public administration were encouraged to define qualities that could be measured both quantatively and in more descriptive ways. Meeting qualitative objectives was typically measured by client surveys or described as overall annual qualitative goals (Pallott, 1998). For instance, in hospitals new ideas of restitution at home supported by hospital facilities, supervision from general practitioners and municipal services allowed patients, instead of lying in hospital beds for several weeks, to recover faster by being more physically active (see for instance Wind et al., 2006; Kehlet and Wilmore, 2008; Pedersen and Huniche, 2011). In this way hospitals could improve patient frequency and rehabilitation, and reduce their waiting lists as their primary objectives by sending the patients to other public service areas near their own home.

The Danish state – as well as other Scandinavian countries – has in general been reluctant to adopt the instruments from the first wave of NPM. Typically the privatization momentum did not have the same effect here as it had in the Anglo-Saxon countries. Budgeting and accounting as well as performance contracting were adopted in some state offices in the beginning of 1990s.4 Privatization or quasi-privatization of the oil and gas sectors happened in Denmark in the mid 1980s, the airports and telecommunication in the beginning of the 1990s, the postal service in the mid 1990s, the electricity sector in late 1990s and the cultural institutions in 2002. Seeing the effects from other countries’ NPM strategies and how these nations changed their management into less counting and more descriptive measurements of quality in public service, inspired a series of reforms in the first decade of the 2000s in Denmark.

Danish reforms have, during the last decade, been implemented in the sectors of education; higher education in 2002, secondary education and the police service in 2007, the water and wastewater in 2007, the waste sector in 2010, the tax institution in 2013, and finally primary and secondary education in 2013–14 (Greve and Ejersbo, 2013). The typical NPM instruments used in Denmark up till today are the creation of independent boards, budgeting and accounting, performance contracts between owners and operators, outsourcing and contracting out services to private companies, performance auditing (benchmarking) and evaluations, and in some institutions and companies LEAN management tools have been introduced.

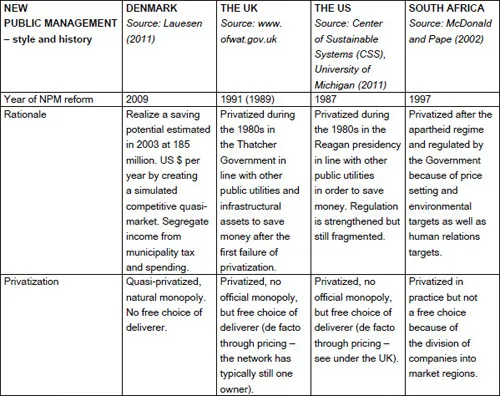

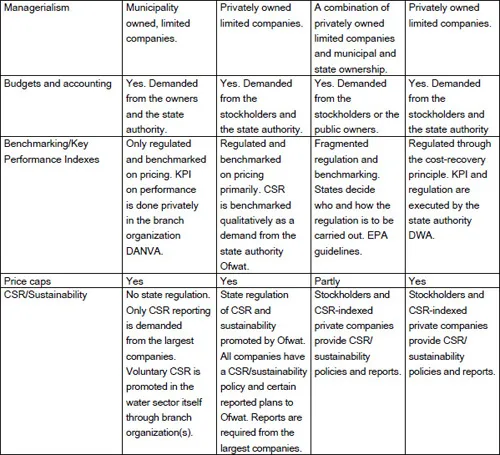

Debates of quality in the public sectors worldwide are still going on, and diverse opinions of the quality of public service have and will always take place. Quality is often converted to more quantifiable measures in the statements politicians, regulators and other public decision-makers, while the receivers of public service, such as citizens and the media, often claim that the quality of the provided service may be impaired (Christensen and Lægreid, 2010; Pollitt and Bouckaert, 2011). Especially in times of financial crisis, where instruments such as the above may be further tightened into more economic savings, these services and instruments may be used to squeeze the lemon further and may create hard times when more needs to be done with less. See Table 1.1 for an overview over the different NPM styles in the nations in which the water companies are located in: Denmark, the UK, the US and South Africa.

Table 1.1 The history and style of New Public Management (NPM)

Source: Lauesen (2014), p. 122.

Note: DANVA – Dansk Vand og Spildevands Forening (the Danish Water and Wastewater Assocation); Ofwat– The Water Services Regulation Authority in the UK; EPA – Environmental Protection Agency (USA); KPI – Key Performance Index; DWA – Department of Water Affairs of the Republic of South Africa.

Throughout the last 20 years, innovation seems to be the word the public sector has been continuously for by adopting business sector management tools to renew the sector and create more value for money (Bowman and Ambrosini, 2000). J.S. Pedersen (2010) analysed Danish reforms during this period and found no evidence that there had been more innovation in the Danish public sector after the introduction of NPM than before. The new innovation of the Danish water sector seems not to come from structural reorganizations and introduction of new business i...