![]() PART I

PART I

On Home and Architecture![]()

1

Homes: A History of a Human Practice

HOMES ARE NOT PRIVATE SPHERES. THEY HAVE NEVER BEEN

We have inherited this subtle notion of the home as a haven and refuge that transcends different conditions and relations of living within the house. Despite its enduring emotional and memory references, we incline to the perception of its personal or private nature. Homes exist in physical space that is socially constructed through various forms, uses and meanings.1 Whereas houses are built to accommodate activities of private life, homes are constructed out of continuities of social-cultural, rituals and patterns of living. We seem to encounter a contradiction in the attributes of the home. How it could be private, while it associates its form, organisation and largely meaning with the commonality of a group, culture or society.2 In architectural terms, homes have always been constructed in groups as a collective effort and inherited methods and techniques.

A social-spatial system of living, the home stood as central to cross-family social life. It is a domain of overlapped public and private life with obligation and trust beyond the family to the expansive formation of the city and society at large. In the second half of the twentieth century, there was a rediscovery of the home as a multidimensional concept3 a multidisciplinary understanding of its formation and evolution as human practice. Indeed, homes are political arenas in which ideologies, positions and dissidence emerge, develop and gather momentum. “The home is a major political background – for feminists, who see it in the crucible of gender domination; for liberals, who identify it with personal autonomy and a challenge to state power; for socialists, who approach it as a challenge to collective life and the ideal of a planned and egalitarian social order.”4 They were are remain central to the society’s interest, ideological reform and social movement in human history.5 But, how has the institution and human practice of home developed to shape our society as we see it today?

Since the mid-1980s, home has been subject a comprehensive investigation from various points of view and research areas: sociologists, environmental psychologists, anthropologists, architects, and historians. However, the abundance of titles on architecture of dwellings, houses, and homes ironically did very little to interrogate the spatial systems of everyday living and as a human practice. The practice of being at home helps clarify the ambiguity behind the socio-spatial systems of domestic environments. In this part of the book, I look at the evolution of homes as socio-spatial systems of the human practice. I tend to confront the perception of homes as housing typologies that are developed out of geographic or temporal condition in isolation from the narratives of accumulating human knowledge. I argue that homes, while being informed by local traditions and social meanings, are a continuum in a long process of a human practice in progress. This chapter tries to unravel the home as a learning process, in which humans are developing forms and spatial systems to respond to fundamental needs. Through this journey, I will look at six key stages of development of the home as human practice; “Home as a shelter”; “From unit to cluster”; “Medieval homes of production”; “Living downtown”; “Homes of modernity”; and “Reversal of the contemporary”. In no case are these categories conclusive. Rather, they are elected to mark an enquiry in the narratives of living that operates beyond the stereotypes of housing forms and function.

MAKING SENSE OF THE HOME

Architecture is the thoughtful making of spaces. The continual renewal of architecture comes from changing concepts of space.

Louis Kahn

Homes have been one of the most explorative and experimental missions of humans in their negotiation with nature. It was a process of discovery not only of the capability of nature, but of oneself. Hence, most philosophers have related the process of building a shelter, dwelling or a home to the state of being in the world. For Norberg-Schults “architectural space may be understood as a concretization of environmental schemata or images, which form a necessary part of man’s general orientation or ‘being in the world’.”6 From Nietzsche to Martin Heidegger and Hannah Arendt, the act of building and inhabiting space is a process of mediation with nature and contextual condition.7 The change of this mediation forces a change in form, spatial configuration and social processes. Man has always created spaces as a medium of understanding of the world.

In the introduction to his illustrative volume, Dwellings, Paul Oliver offered a critique to the shortcomings of architects’ vision of the tradition of building that ranged from the contextual ignorance of early Renzo Piano work to the axioms of “form follows function” and other modernists’ categorical view of the world.8 For Oliver, dwellings are products of the past in forms that satisfied societies in earlier times, yet they continue to mediate changing ways of living: “Dwellings may outlast lineages and in some cultures may be re-occupied or adapted, their survival to the present being a testimony to their responsiveness to changing life-ways”.9 Aligning the three notions of “vernacular”, “dwellings”, “past” is explicit in the way Oliver looks at the act of building as a tradition that contrasts somehow with the professional attitudes of the present. Dwellings are conceptually seen to emphasise the dichotomy of different worlds, the past versus the present, the vernacular versus the professional, and the peripheral rural versus the progressive urban; a typical 1980s post-modernist appreciation of traditional practices. Yet, Oliver’s focuson the rationale behind building processes, materials, structure and the instinctive response to environmental challenges is one of the most comprehensive and constructive accounts to date.10

Aside from the dichotomy of the past and present, there will always remain something about the home that is unmeasured, but dictates judgement, perception, and inhabitation of the home. Everyone accords different attributes to the environment and space he/she calls home, which could be in the most awkward of places but appear as tangible and credible experience of living. From caves and huts, to informal apartment towers that besiege Mumbai and Cairo and informal shantytowns that in Tijuana, Jakarta or Mexico City, homes could exist in vastly contrasting forms of living and socio-spatial systems. To make sense of these homes, one must engage with the patterns of everyday living and needs of their residents that enable, according to Teddy Cruz, the creative building of the built environment.11

HOME AS A SHELTER

Shelter was the first experiment in transforming natural materials into construction systems for the sake of protection and accommodation of social engagement. Three early unitary shelters: the tent, igloo and cave, were simple processes of carving a volumetric space within liveable contextual settings. However, they could not operate on their own or in isolation from spatial and natural surroundings. Rather, they were part of a larger system of networks: supplies and primitive infrastructure (water, food, crops, animals … etc.) and a social and ecological system of which animals and plants were essential components. These systems of unitary shelters were more complex than what their appearance suggests. Aboriginal Australian tribes, for example, draw their social territories much wider than the space of the tents. They undertook basic daily activities including cooking and sleeping outside the tents. Tents, hence, were arranged at measurable distances to allow for a sense of privacy and freedom of social practice and communication without incursion by others.12 Similarly, the existence of the Bedouin Arabs is partly, as Ibn Khaldoun recognised, “the negation of building”.13 Their life depended on the mobility of the nomads, suspicious of cities and settlements. Many Bedouins tribes in Sinai, the Grand Sahara and the Arabian Peninsula refuse to settle in houses as it negates the notion of limitless boundaries that allow them to inhabit the desert as a way of life.

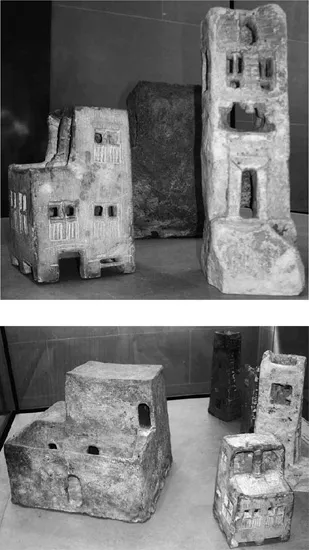

The shift from the tent to the house was a step in associating the individual unit with structures of permanent settlements. Settlement suggests the permanence of living patterns, alongside water resources for farming and transport, leading homes to become spatially and physically defined. Early settlement homes encompassed a series of chambers that were used for the storage of food, protection of animals as well as accommodating spaces for inhabitants. Models of ancient Egyptian houses found in ancient tombs display the basic association and need for two parts of the house, the enclosed shelter for living and the outdoor court for cooking, livestock and domestic work (Figure 1.1). When spaces were not available, the house had to be vertically organised without private courtyards. This system was later developed in the early Arab city of Al-Fustat, which at the peak of its evolution had a dense landscape of high rise residential buildings that according to the contemporary travellers featured prominent heights above city walls, in a similar manner to those we see today in the desert Yemeni town of Shibam.14 Houses were a series of compact apartment buildings, vertically organised for the workers occupants. Large courtyard houses were mainly built by wealthy elites and merchants.15 Extended families resided in more combined arrangements of houses with different wings of variable privacy, forming early versions of the medieval urban landscape.

1.1 Models of Ancient Egyptian houses dating back to the first century BC

Large houses of the Ancient Egyptians and the Romans followed similar arrangements. Organised around two courtyard spaces, one was for family living and activities like cooking, eating and socialising, while the other was for stables and livestock. Both offered internal yet outdoor environments to provide ventilation and fresh air in the warm Mediterranean weather; always protected by relatively high walls and organised over two storeys, with most private spaces, like bedrooms and associated services, placed on the higher level. These homes enjoyed a complex social hierarchy within the home, especiallt with the presence of servants, whose accessibility privileges are different to other occupants.

FROM UNIT TO CLUSTER: SPATIAL SYSTEMS OF HABITAT

The emergence of the community has been a subject of debate, with Jamil Akbar wondering whether the social forces derived the physical development of settlements like alleyways, lanes or communities, or whether the opposite was the case, with physical settings leading social integration and cohesion.16 In Jane Jacobs’ notions of community, the feeling of proximity within the street is what accords the attributes of home to issues of security, intimacy and direct social interaction in the locality. The home lies in-between the houses and not in the physical characteristics of the house itself.17 This is what transforms the static and rigid physical space into dynamic socially-cohesive and culturally intense venues. In this sense, shared spaces of local communities shaped the culture of home through inter-family interaction.18 With the idea of clustering a series of houses to make a “community of parts” dominating the early formation of the town, we find some of the old quarters of the urban metropolis remain faithful to this system today.

Clustering takes different arrangements with overlapping of territorial boundaries between individual units making the case for a habitat in which ...