![]() PART I

PART I

Art, Rhetoric, Style![]()

Chapter 1

Shakespeare and the Art of Forgetting

Stephen Orgel

This is a talk about forgetting, or the suppression or subversion of memory, as the essential creative principle – we memorise in order to forget. My primary example is Shakespeare, but he is only the example I know best: Shakespeare in this can hardly be unique. I have in mind both really big creative acts like forgetting that the Lear story has a happy ending, or forgetting the deaths of Mamillius and Antigonus in constructing the transcendently happy ending of The Winter’s Tale; and really small but even more baffling creative acts such as in As You Like It introducing a character named Jaques and forgetting that there is already a character named Jaques in the play, or in the second part of Henry IV introducing a character named Lord Bardolph when there is already a character named Bardolph in the play, or in The Comedy of Errors calling Adriana’s servant Luce the first time she appears, and in the next scene calling her Nell; or at the beginning of Othello describing Cassio as ‘almost damned in a fair wife’ and then having him unmarried for the rest of the play, or in The Tempest listing Antonio’s son as one of the shipwreck victims and then never mentioning him again – there are many more such examples in Shakespeare. And (how could it be otherwise?) the process of constructing the Shakespeare we want has for the most part also been a process of forgetting about these elements of Shakespeare’s creative process. Such examples, however, are surely keys to the act of creation – this is the essential Shakespeare, the essence of drama itself. Anthropology tells us that drama begins as ritual, but ritual is an act of memory; it only becomes drama when it forgets and revises, when plots become unexpected, when the end forgets the beginning, when every performance forgets the previous one, and forgets the text it purports to follow, when every text emends the last, hoping to consign to oblivion all except the forgotten but endlessly restored original.

My main example will be the case of King Lear, but I begin with an Italian example, which is especially germane because it has to do with the imagination of history – what history conceived as drama remembers, and what, in order to become drama, it forgets. In May 1671, a remarkable tragedy set in an England that was almost contemporary was performed in Modena. Girolamo Graziani’s drama about the English Civil War, Il Cromuele, was published in the same year, with a lavish dedication to Louis XIV and a preface declaring the playwright’s intention of transforming the practice of the stage. The book is a manifesto, and was published with illustrations, five engravings of settings for each of the five acts.

The polemical preface is more notable for its lacunae than for its argument. Graziani points out that his villainous protagonist, ‘Cromuele, Tiranno d’Inghilterra’, hardly requires a justification, given such classic models as Medea and Thyestes. The novel element, Graziani says, is the choice of a contemporary subject – Charles I had been beheaded only 22 years earlier; Cromwell had been dead for little more than a decade; and both Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth and the Earl of Clarendon, who are characters in the play, were still alive in 1671. The issues of the tragedy were the stuff of current European politics. This is what Graziani claims as revolutionary in his dramaturgy: the fact that its pity and terror are contemporary.

However, there are in fact several notable precedents in Italian drama. The most influential was Federico della Valle’s La Reina di Scozia of 1595, written less than a decade after Mary Stuart’s beheading; the play was revised and revived several times in the seventeenth century as Maria Stuarda. There were, in addition, two other plays with the same title, both produced as recently as 1665 – Mary Stuart offered an obvious parallel to the subject of Cromuele, especially given the fact that she was Charles I’s grandmother. In fact, considering the number of Maria Stuarda plays, the only really surprising thing about Graziani’s choice of subject is his apparent ignorance of them. In the English theatre, moreover, the use of modern history as a subject, especially current events in France, was almost normative. Marlowe’s The Massacre at Paris, Chapman’s Conspiracy and Tragedy of Byron and the two Bussy d’Ambois plays, enlisted the stage in the emergent cause of Protestantism and warned of the dangers of the rampant aristocratic ego – the particular dangers dramatised were recent, and ongoing. Even Shakespearean histories like Richard II and Henry VIII were felt to be dangerously contemporary in their relevance. Graziani, for all his invocation of British history, clearly knows none of this – the greatest lacuna in his argument is the dramatic tradition itself, both English and Italian.

The play is a rich amalgam of high romance and heavy rhetoric, with an elaborate multiple disguise plot. The language is operatic – indeed, much of it is intended to be sung. Though the background is the Civil War and the characters are based on – or at least bear the names of – real people, the drama in fact has nothing to do with history. Two young men, Edmondo and Henrico, have arrived in England from the continent to rescue King Charles, who is imprisoned in the Tower of London (in fact, the king was incarcerated first on the Isle of Wight and then in Windsor Castle). They enlist the help of Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth, who is secretly in love with the king, of her confidante Orinda, mother of the governor of the Tower of London, and of Anna, daughter of the Earl of Clarendon. Both young men are women in disguise: we learn immediately that Henrico is Queen Henrietta Maria, the wife of Charles I, and Edmondo is revealed at the very end as Cromwell’s (fictitious) daughter Delmira, a closet royalist also secretly in love with the king. The elaborate rescue plot falls apart through a combination of jealousy, bad timing, and – the truly revolutionary element in the play – an overheard soliloquy. Edmondo, seeing his plans about to succeed, and believing himself alone onstage, rejoices:

Già veggo

Libero il Re, schernita Elisabetta,

Confuso Cromuel, delusa Orinda.

And Orinda, the unseen audience, at once precipitates the catastrophe in truly operatic style: ‘Ah perfido, vendetta!’ … and the jig is up. Edmondo is denounced, the plot revealed, the king and his fictitious admirer carried off to execution. It is not revolutionary politics but this violation of dramatic convention, the overheard soliloquy, that results in the death of the royal martyr.

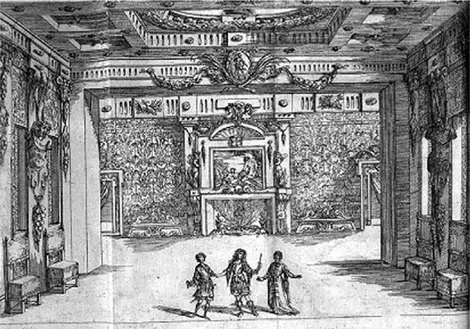

The only parallel I know to this occurs at a critical moment in Guarini’s Il Pastor Fido, when the heroine Amarilli laments her forthcoming marriage in a soliloquy which is overheard by her rival in love, the villainous courtesan Corisca. The overheard soliloquy becomes the basis of a plot to supplant and destroy Amarilli. The parallel – or perhaps source – is significant: Il Cromuele is pure romance. The illustration to Act I shows a stage set as substantial as any palatial salon of the age, but the three figures are in the fantastic costumes of court masques (Figure 1.1). The men especially (who are of course cross-dressed women) look like knights in a ballet de cour of Orlando Furioso, rather than Royalist gentlemen. For all its contemporary claims, this is the world of epic fantasy. In fact, this scene itself is a fantasy: the characters in Act 1 are Edmondo, Anna and Orinda; but the second young man, on the left, can only be Henrico, the cross-dressed Queen, who does not appear until Act 2 (it looks as if the illustration was originally designed for Act 2).

The setting for Act 2 is a sumptuous London parterre that looks suspiciously Italian – there are conical cypresses in the background: they don’t do well in the English climate. The two impassioned figures are Henrico, the disguised queen Henrietta Maria, and Odoardo, otherwise Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon. In Act 3 we are finally in the Tower of London in the presence of Arthur, the governor of the Tower and the king’s jailor, and a shrouded woman, Orinda, his mother, who is persuading him to take the mysterious Henrico into his service. The Tower is a majestic baroque invention, half fortress, half palace, exhibiting overtones of Bibbiena and Piranesi, but not a trace of its Norman origins. Act 4 takes place on the ramparts of the Tower, though we seem to be at sea, or at least river level, with a lovely view of a very Italianate cityscape with a Palladian church on the south bank and a bridge that can only be London Bridge, since that was the only bridge over the Thames. The scene is populated by another group of court ballet figures – attended, to be sure, by four credibly attired seventeenth-century guards (the figures with the pikes) (Figure 1.2). And in Act 5 we see Cromwell, asleep in a chair in the royal bedchamber which he has usurped, afflicted with very bad dreams.

These images are a good indication of the limits to the imagination of otherness. Doubtless very few of the Modenese spectators would have visited London, so recreating real buildings would have had little point; but these settings nevertheless would obviously have been quite recognisable. Graziani’s England, for an Italian audience of 1671, was a very familiar place, both geographically and theatrically, and the story itself depends on forgetting the events it purports to depict. If the play is at all revolutionary, as Graziani claims, it foretells not a drama that brings history to life, but romance validated by a veneer of history – a thin veneer at that: its descendants are operas like I Puritani and the novels of Dumas. The most striking thing about it is surely the most characteristic thing about it: its claim of authenticity – Shakespeare similarly titled his fantastic romance about Henry VIII All Is True. But the truth of theatre is always a mass of contingencies, and the stage always constructs its own reality.

Figure 1.1 Girolamo Graziani, Il Cromuele (1671), plate to Act 1.

Figure 1.2 Girolamo Graziani, Il Cromuele (1671), plate to Act 4.

I turn now to a famous emendation, which is germane because it depends on a case of memorial reconstruction – a case, that is, in which it would appear that Shakespeare’s genius was both materialised through an act of memory, and at the same time obscured or even vitiated by it. Here is the account of Falstaff’s death given by Mistress Quickly in Henry V. ‘… His nose was as sharp as a pen, and a table of green fields … .’1 This was the text from 1623 until 1733, when the editor Lewis Theobald decided that Shakespeare’s manuscript had been misread: that ‘a table of green fields’, which seems to make no sense, in fact had nothing to do with the matter, but that rather, in dying, ‘ ’a [=he] babbled of green fields’. This emendation, indisputably a stroke of editorial genius, seemed to have restored what Shakespeare must actually have written. Bibliography here communicated with Shakespeare himself – or at least, with Shakespeare’s manuscript before it reached the printer.

But let us pause over this editorial watershed. If we agree that Theobald was correct, and that a compositor setting the type in the printing house was misreading Shakespeare’s handwriting, what happened before the play got to the compositor? ‘Table’ is the 1623 folio’s reading; so the folio’s printer is the culprit. But the only other substantive text, from the 1600 quarto, in a passage that bears little resemblance to the folio text, at this point reads not ‘babbled’ but ‘talk’, and it is apparent that the folio was not set up from this very garbled quarto, but directly from Shakespeare’s manuscript. So neither of our two primary sources reads ‘babbled’: ‘babbled’, even if it is impeccably correct, is all Theobald. Q seems to be a reported text provided by two actors – the creativeness of the ars memoriae in this case is only an index to its radical fallibility – but if F’s ‘table’ is a misreading resulting from a visual error in deciphering Shake...