![]()

Chapter 1

Chiara Gambacorta and the History of San Domenico of Pisa

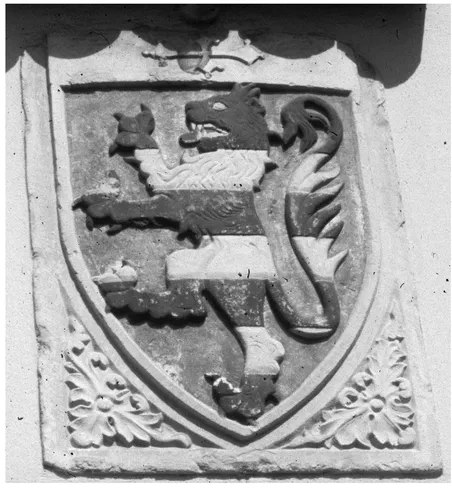

Just south of the Piazza dei miracoli and the Leaning t ower in Pisa, on one of the narrow streets that run towards the River arno, an arch in one of the walls that define the street is adorned with a coat of arms (Figure 1.1). This is the only marker on the street of the presence of the convent of San Domenico of Pisa. Significantly, the arms are of the Gambacorta family, signaling this family’s patronage of the convent, and the identity of its most famous inhabitant. inside the small church a visitor may see the preserved body of the foundress, chiara Gambacorta, and the fifteenth-century sculpted tomb slab that once covered that body (Figure 1.2). This community is a living link to one of the most important female Dominican houses in Italy in the fifteenth century. The vicissitudes of the modern world have not been kind to this community, but the calm of their house in Pisa belies the troubles they have endured.

The body of the foundress is the most important relic that the modern community has preserved from the fifteenth century. Most of the other works of art and items of value were long ago destroyed or removed to museum collections. The identification of these works and the reconstruction of the decorative program is a major goal of this book. This chapter begins the story of these works of art, by introducing the figure of the foundress of the community and situating her life and achievements within the history of Pisa and the Dominican Order. The chapter will also consider the intellectual and social climate of the convent.

The Life of Chiara Gambacorta

The convent of San Domenico was founded through the efforts of Chiara Gambacorta, whose history and spirituality marked the character of the convent. She was a strong-minded and self-assured woman, who turned her family’s resistance to her vocation into their financial and personal support of her new foundation. Inspired by the example of Catherine of Siena, Chiara made her convent the wellspring of the Dominican Observant movement.1 Born in 1362, Chiara was the daughter of Pietro di Andrea Gambacorta, the ruler of Pisa from 1369 to 1393. The Gambacorta family had played an important role in Pisan politics and society throughout the fourteenth century, producing in addition to numerous political leaders, an archbishop (Lotto Gambacorta) and another Beato, Chiara’s cousin Pietro Gambacorta, who founded the order of the Penitence of St Jerome.2 The name of Chiara’s mother is less certain.3

1.1 Stemma of Gambacorta family, seventeenth century

Pietro Gambacorta’s only daughter, called Tora (a diminutive of either Theodora or Victoria), was born while her family was exiled from Pisa. As a pawn in her family’s dynastic politics, she was betrothed at age seven (during the year her father returned to Pisa and took the reins of government) and married at age 12, in 1374, to a member of another important Pisan family with political ties to the Gambacorti, Simon da Massa.4 Although Tora had displayed an early dedication to chastity, she obediently acceded to her family’s insistence on marriage.5 Her vita describes her mortifications of the flesh and charity to the poor both

1.2 Portrait of Chiara Gambacorta from her Bara, c.1420

before and within her marriage. Her husband died in 1377 after three years of marriage.6

The young widow tried to avoid what was certain to be another politically arranged marriage. In a letter written to her about this time, Catherine of Siena, whom Tora probably had met during the saint’s sojurn in Pisa in 1375, encouraged her efforts to renounce the world.7 In desperation, Tora secretly entered the nearby Franciscan convent of San Martino, where she took the name Chiara. Her enraged family forcibly removed her from it, threatening the entire community unless she returned home. She endured five months of virtual imprisonment in her father’s house, although she still managed, with the help of a disciple named Stefano Lapi, to distribute what wealth she still controlled to the poor.

In the fall of 1378, Pietro Gambacorta asked Alfonso Pecha da Vadaterra, a friend and fellow pilgrim to Jerusalem, to convince Chiara to obey his wishes and consent to another marriage. Alfonso Pecha da Vadaterra, the Archbishop of Jaen (Spain), had been the confessor of the Swedish mystic, Birgitta, whose Revelations he edited and distributed.8 In spite of his friend’s commission, Alfonso encouraged Chiara’s vocation and taught her about Birgitta. According to Chiara’s vita, Alfonso gave her a book of Birgitta’s “Histories” and Chiara took Birgitta as a special patron.9 Facing such opposition, Chiara’s father finally capitulated. For reasons not articulated in her vita, instead of returning to the Franciscan house of San Martino in Kinzica, Chiara entered the Dominican convent of Santa Croce in Fossabanda (just outside the walls of Pisa) on November 30, 1378.10 Pietro Gambacorta promised at this time to build a new convent for his daughter.

Chiara found the conditions at Santa Croce too relaxed for her interpretation of the religious life. While a part of this community, she tried to adhere more strictly to the Rule than most of the sisters and obtained permission to pray and perhaps even to live apart from the other nuns.11 After the death of Chiara’s mother, Pietro Gambacorta married a noble Genoese woman, Orietta Doria, who encouraged the building of the new convent.12 Thus prodded, Gambacorta purchased the necessary structures and land to inaugurate and endow the new convent, and in June 1382, Chiara and five other women from Santa Croce moved into the new institution. This small community included Filippa Albizzi, the first prioress, Maria Mancini, Andrea Porcellini, Agnese Bonconti, and Giovanna Del Ferro; most of these women were daughters of Gambacorta’s political allies.13 The new community received official sanction with the Bull of Urban VI dated September 17, 1385. While Pietro Gambacorta was the Rector and Patron of the convent, the frate of the Dominican house of Santa Caterina served as confessors and protectors.14 Their first confessor, Fra Domenico Peccioli of the convent of Santa Caterina, wrote a chronicle and some vitae of the early years of the community.15

The Gambacorta government in Pisa was brutally overthrown on October 21, 1392, when Pietro Gambacorta was assassinated by an erstwhile political ally, Jacopo d’Appiano, who then seized power. A dramatic passage in her vita reports that Chiara’s brother Lorenzo fled the assassins and sought asylum in San Domenico.16 Chiara feared that the assassins would follow him into the convent, break the seal of cloister, and endanger the nuns. She also feared that her brother would be excommunicated for himself having violated the cloister. She refused to admit him, he fell into the enemy’s hands, and he died several days later. In making such a terrible decision, Chiara must have vividly remembered the trauma of her own family’s invasion of the cloister of San Martino 16 years earlier.

Both the political and the financial fortunes of her family were overturned by these events, and many members of her family were killed or exiled. Her stepmother seems to have entered the convent at this point. In 1398, when the Appiano political fortunes turned, Chiara welcomed into the community the wife and daughters of the man responsible for the deaths of her father and brothers. In her vita and later imagery, this action was lauded as an example of her charity and forgiveness. Her refusal of her brother’s entry into the convent was a sign of her allegiance to the new family she had created at San Domenico.

Chiara became prioress of San Domenico in 1395, having served as subprioress for ten years. (These offices were only inaugurated when the community received papal sanction in 1385.) She was only 33 in 1395, still quite young to be prioress: the Dominican Constitutions recommend that someone at least 40 years old hold this office. While engaged in providing for the material and spiritual well-being of her community she also conducted an active ministry beyond it. Through acts of charity, and written exhortations to other religious and to members of the laity, she offered an example and counsel to others. The convent was a constant giver of alms, and Chiara directed some gifts intended for her house to other charitable institutions.17 Dedicated as she was to careful observance of her order’s Rule, Chiara was quick to criticize dereliction to duty, especially by the religious. According to the vita written by one of her sisters, if Chiara heard of a wayward priest she would send for him to hear her confession and spend the interview castigating him. The vita also describes Chiara’s propensity to offer advice and counsel:

With sweet charity Chiara did her best to draw out each one in order to do him good. She spoke of God in the most wonderful manner, and there was no one who did not heed her and strive to change his life. She had spiritual sons and daughters in every walk of life. Her lips abounded with words of salvation, her tongue never ceased to praise the works of God. In order to render her word more efficacious, God gave to Sister Chiara the gift of discernment that she might know the interior movements of the mind. Knowing the sentiments and feelings of her subjects, she was better able to lead them aright. She had a spirit so kind that when she talked with a person she was able to understand his interior feelings, and often told the Sisters what temptations they were undergoing. Truly it was not always agreeable to have her about; but in her position of authority, this gift helped much to her success and her charity in using it was a real consolation.18

This picture of Chiara as perhaps somewhat overbearing is corroborated by an anonymous pastoral letter addressed to Chiara, the principal theme of which is the difficulty of correcting others and exacting obedience.19

Chiara’s correspondents included seculars and religious, the lowly and the high. She corresponded with the Master General of the Dominican Order, and the leader of the city of Lucca, but the best surviving evidence of Chiara’s apostolate is revealed by her correspondence with Francesco di Marco Datini, the famous “Merchant of Prato,” and his wife, of which 14 letters survive. These letters have a pastoral tone; they urge Francesco to prayer, to charity, and to devotion to Mary. Chiara seems especially interested that Francesco and Margherita read; in a letter to the latter written probably in 1395, she writes: “It gives me great pleasure to learn that you know how to read, and I pray you make use of your knowledge. For the Saints have taken pains to write books, that we may see ourselves therein, and that we may adorn ourselves with virtue, and that we may remove the stains of sins which pollute the soul.”20 The letters give us a glimpse of her level of education, as well as her spirituality.

We are encouraged to believe that Datini profited by Chiara’s letters, not only because of their number, but because of the documented reaction to them.21 For example, Ser Lapo Mazzei, Francesco’s notary, wrote ...