![]()

Part I

The Challenges of Urban Development Processes

![]()

Chapter 1

Asian Urbanization and Local and Global Environmental Challenges

Hans J.A. van Ginkel and Peter J. Marcotullio

Asia has experienced rapid development and urbanization in the last half of the 20th century. The transformations have reached unprecedented scales. Many indicators have been used to demonstrate the improvement in overall human well-being, notably those advancements related to income, longevity and some health measures, but this only tells part of the story. The great transformations now in process have been accompanied by both local and global challenges to environmental sustainable development. Moreover, there are indications that the challenges will increase in intensity into the future. It is crucially important to identify the dynamics underlying these developments and point to policies that could begin to address their impacts.

This chapter describes the economic and urbanization transformations experienced by Asian cities. It then explores some of the local and global environmental challenges that have accompanied these changes. Specifically, for local issues, we identify the ‘infrastructure time-bomb’ – defined as the overburdening of old, out-of-date, and overused basic infrastructure (e.g., water supply and sanitation) – within some of these cities. Future urbanization will only increase the burden on these structures and if not addressed, the situation may grow into a crisis.

In order to address these issues, integrated approaches to planning and urban management are needed. We look to specific examples within the Netherlands to see how a small country, characterized by high population density, solved its resource and spatial planning challenges. The results suggest some lessons for Asian cities. Finally, these observations and analyses have encouraged the United Nations University (UNU) to rethink the direction of its Urban Programme. The last section presents thoughts on how this new program will provide research and capacity building to help address these issues.

Asian Urbanization and Local Environmental Challenges

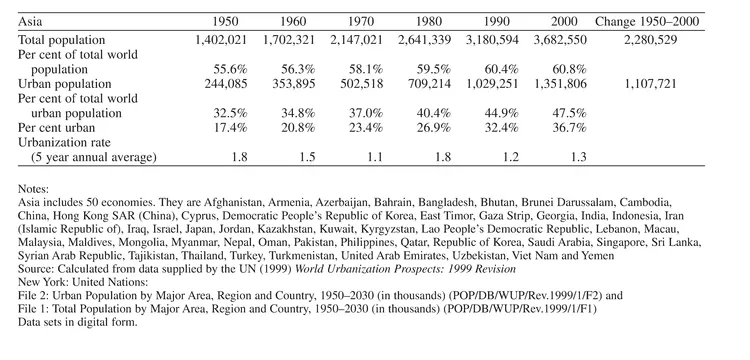

Asia has been undergoing a rapid and intensive urban transition. As Table 1.1 demonstrates, since 1950 more than 1 billion people have been moved into the region’s cities, bringing the percentage of urban population up from 17 to more than 36 per cent. This immense process of urbanization is far from over. With only 38 per cent of the region’s population currently living in dense human settlements,

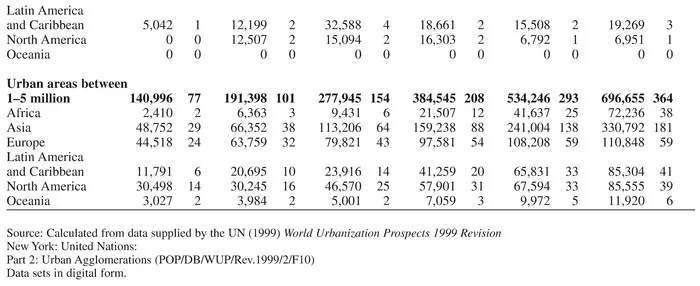

Table 1.1 Comparative aspects of Asian urbanization (population in thousands)

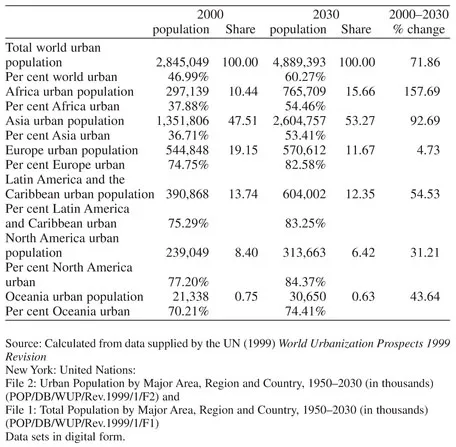

the next 30 years will bring even greater changes (see Table 1.2). Approximately 1.25 billion of the total 2 billion inhabitants added to global urban population will end up in cities in Asia by 2030. This will change Asia’s urbanization rate from 36 to 53 per cent and increase the region’s share of the world’s total urban population. It is estimated that by 2030 more than 53 per cent of the total global urban population will be found in Asia.

Asian urbanization has occurred at some of the fastest rates in history. The average increases for the region varied between 1.2 and 1.8 per cent, but this masks the high speed of change in some countries. For example, South Korea’s annual urbanization rates were over 3 per cent from 1960 to 1980, and for the years 1965 to 1970 reached 4.6 per cent. Thus, not only does the absolute number of individuals

Table 1.2 Comparison of size and share of urban populations by region, 2000 and 2030 (population in thousands)

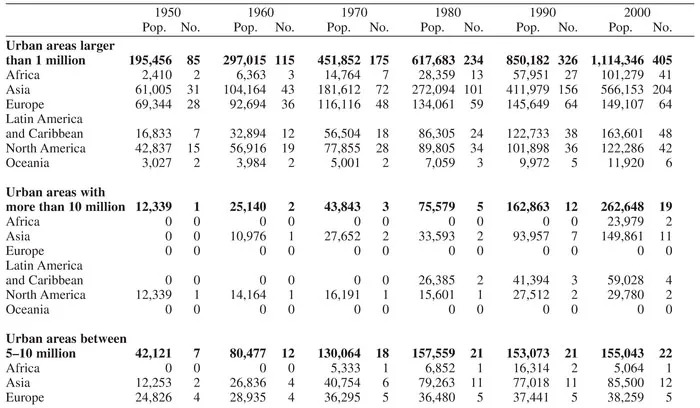

Table 1.3 Regional comparison of growth in large urban areas, 1950-2000 (population in thousands)

moving to cities in the region dwarf anything previously experienced but the rates of increase are also unprecedented.

Another feature of Asian urbanization is the rise of large urban agglomerations. Table 1.3 demonstrates the rise of these urban agglomerations since the middle of the 20th century. The total number of large cities (i.e., those greater than 1 million) climbed from 85 in 1950 to 405 in 2000. The largest per cent increase among the different sizes of cities was the ‘mega-cities’ category (i.e., those equal to or greater than 10 million inhabitants). According to the UN (1999), there was one mega-city in 1950, but this number increased to 19 by 2000. Of the 19 mega-cities in the contemporary world, 11 (i.e., 58 per cent) are located in Asia. Indeed, Asia has dominated over other regions in terms of the emergence of large cities in all size categories (see Table 1.4).

Table 1.4 The world’s urban agglomerations, 2001–2015 (>106 inhabitants in 2001)

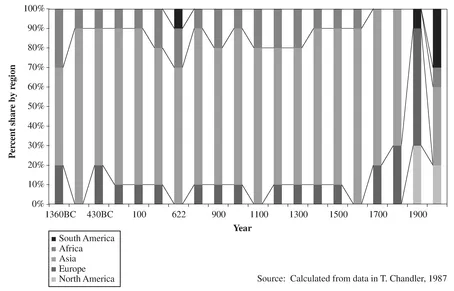

History has shown, however, that Asia has always been the location of the world’s largest cities. The shift of large cities to North America and Europe during the late 19th and 20th century can be seen as a fluctuation rather than a long-term trend. Figure 1.1 demonstrates that most of the largest 20 cities in the world at different points in time since 1350 BC have been located within Asia. In early times large African cities were located in Egypt, but in later periods large cities appeared in central and southern Africa. Those of early Europe were located in Greece and Italy, but locations changed later to include more Western European countries. Early large Asian cities were first located in Asia Minor, the Middle East, China and South Asia. Between 600 and 800 AD, Japanese and Southeast Asian cities were included in the list of the world’s largest cities. Mexico’s Teotihuacan was included for a brief period. It was not until contemporary times that cities in North, Central and South America had surpassed others in the world. While cities in Europe and North American grew to a large size much more rapidly than their predecessors as a result of the Industrial Revolution, the new millennium will once again see the rise of large cities in Asia (see Chandler 1987).

Figure 1.1 Regional shares of world’s 20 largest urban areas, 1360 BC to 2000 AD

The number of large cities will continue to increase in the medium-term. The UN predicts that by 2015, the number of mega-cities will increase to 23 (see Table 1.5). In the next 15 years, however, it is the middle size large cities (i.e., those from 5 to 10 million inhabitants) that will gain the largest numbers and increase in relative size. It is interesting to note that while the proportion of the urban population is expected to dramatically rise, the proportion of those living in mega-cities is not. Large cities are growing more slowly than others. The UN projects that of the total urban population, the mega-cities will continue to maintain a share of approximately 12 per cent in 2030, a fraction of a percentage higher than in 2000. Most of the urban population (approximately 60 per cent) will continue to live in cities with less than 1 million inhabitants.

Table 1.5 Share comparisons of various sized urban regions, 2000 and 2015 (population in thousands)

Local Environmental Issues in Asian Cities

The growth of cities in Asia is not without its challenges. Many cities within the region have significant ‘brown’ agenda issues, including the equitable provision of water supply access and sanitation. These services are tightly linked with adequate housing and poverty. Those without adequate access to these services are often found in slums or squatter settlements and the lack of access to basic infrastructure exacerbates problems associated with low incomes. Indeed, without appropriate infrastructure urban areas are among the world’s most life-threatening human environments and half the urban population in Africa, Asia and Latin America are suffering from one or more of the main diseases associated with inadequate water and sanitation provision (World Health Organization 1999). Water, sanitation and hygiene risks are associated with 2.2 million annual deaths and diarrhea alone causes 6000 deaths per day, mostly among children (UN-Habitat 2003).

Local environmental challenges dominate low-income cities (Hardoy et al. 2001; McGranahan et al. 2001). In Asia the challenges are particularly acute. Table 1.6 presents the numbers of those without access to adequate water supplies and sanitation in Asia. These figures are, indeed, significant. Even though the percentage of those in Asia without adequate infrastructure for these life supporting needs are as high as those in Africa, the absolute numbers in Asia are over three times greater than in Africa or Latin America.

Table 1.6 Estimates for the proportion of people without adequate provision for water and sanitation in urban areas of the developing world

| Region | Number and proportion of urban dwellers without adequate provision |

| Water | Sanitation |

|

| Africa | 100–150 million (ca. 35–50 per cent) | 150–180 million (ca. 50–60 per cent) |

| Asia | 500–700 million (ca. 35–50 per cent) | 600–800 million (ca. 45–60 per cent) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 80–120 million (ca. 20–30 per cent) | 100–150 million (ca. 25–40 per cent) |

It must be noted that the numbers in Table 1.6 are based upon estimations. Exact comparisons are extremely difficult to make, as there is little agreement as to what constitutes ‘adequate’ living conditions. At the same time, situations have been documented in individual cities that suggest similar results. For example, in many cities of the rapidly developing Asian region, it is not uncommon that large sections of the population use water that is contaminated and have no provision for sanitation in their home (Hardoy et al. 2001). Moreover, even in ‘successful’ cities, such as Bangalore, almost a third of the population is without direct access to water and must draw water from public fountains (ibid).

Many of these cities are surviving on colonial infrastructure that has been taxed beyond limits. Further, the urbanization within Asia that is expected to continue into the early 21st century is largely within the least developed or low-income economies of Asia. These are those governments that have the fewest resources to provide services. One way to assess the scale of the problem is to match projected challenges against what the international community has set as a goal to overcome. Target 10 of the UN Millennium Development Goal 7 seeks to half the proportion of people without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation by 2015, and target 11 seeks to achieve a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers (defined as people currently without adequate housing and basic services) by 2020. The latter target falls well short of the 924 million people presently estimated living in slums (Payne and Majale 2004). Between 2000 and 2020, the UN predicts that in low and lower-middle income countries in developing Asia alone there will be an additional 364 and 408 million people added to cities (see Table 1.7). Hence, local environmental challenges are significant and will remain so for the region into the foreseeable future.

Table 1.7 Change in urban population within Asia by income status, 2000–2020

| Country status | Countries (n) | Urban population 2000 (in thousands) | Urban population 2020 (in thousands) | Change 2000–2020 (in thousands) |

|

| Low income | 17 | 450,262 | 814,373 | 364,111 |

| Lower-middle income | 17 | 704,570 | 1,113,529 | 408,959 |

| Upper-middle income | 4 | 36,378 | 61,265 | 24,887 |

| High income | 12 | 160,599 | 176,435 | 15,836 |

Asian-style Globalization and Global Environmental Challenges

At the end of the 20th century, the world economy experienced structural adjustments affecting production, resource utilization and wealth creation. Cross-border functional integration of economic activities and growing interdependencies among regional economic blocs are part of a set of processes defined as globalization. Evidence for the geographical scope of globalization usually includes the locations of nodes within the flows, while the intensity of globalization is generally given by a number of trend indicators including trade and financial flows, foreign direct investment (FDI), communications (i.e., information flows) and personal and business travel. The increasing scope and intensity of global economic integration has been underpinned by advances in technologies facilitating communications and transportation.

Globalization has not impacted nations evenly. Those in East and Southeast Asia have experienced the rapid development of a manufacturing belt with high accession rates in secondary economic activity and growth. While most of the world’s manufacturing production is still located in OECD countries like the United States, Japan and Western Europe, there have been significant changes in the geography of manufacturing output. In all of the G7 countries, the share of manufacturing in GDP dropped significantly from 1960 to 1993. In the United States from 1979 to 1995, as many as 24.8 million ‘blue-collar’ jobs were extinguished and new employment was not generated in the manufacturing sector. This decrease in manufacturing employment has translated directly into lower production levels. In terms of world share, the manufacturing output from the USA has declined from 34.4 per cent in 1965 to 25.7 per cent in 1992.

With the loss of manufacturing ...