![]() PART I

PART I

THE ROOTS OF ITALIAN URBAN FORM ![]()

1

Rome: The centre of the city as axis mundi

The history of Italian architecture and urbanism is haunted by the image of Rome and the traces of its rule. That presence is felt in different ways, either as the morphological origin of the contemporary urban pattern, as the source of a general attitude towards civic values often expressed through the imitation of its forms and iconography, or as a mythical ideal of urban order. These different legacies of the ancient culture to the cities which followed them, both within Italy and elsewhere within the scope of Rome’s empire, are intricate and often hard to unravel, extending from archaeological evidence to fanciful speculation. However, the type of distinction between scientific research and retrospective imagination which we are able to make today is not necessarily useful to the meaning of the historical phenomenon, despite its relevance for the understanding of the contemporary urban situation. The decline of the interpretation of the natural and urban environment as a phenomenon charged with spiritual significance is intimately connected to the separation of the functional aspects of the city from the expression of any transcendent ethos. Historically the religious reading of the natural and physical world which underlay the construction of ancient urban situations predisposed the citizens to an appropriation of the city as a revealed truth (Fustel de Coulange [1880] 1955; Rykwert 1976). In that context the mythic interpretation of cities might be considered to have primacy over the broad facts of its form. To the ancient minds which created urban spaces there was a correlation, which would normally require expert interpretation, between their immediate physical situation and the observable phenomena of the wider world around them. Settlements were viewed as manifesting the direct intervention of the divine in the mundane, and therefore the spiritual function of cities – their role as theatre of the civic cult – has to be appreciated by the contemporary mind if one is to understand the range of their psychological as well as physical effects. This poetic life of the city has effectively been superseded by a combination of utilitarian and formal methods which have no anchor in any cultural tradition.

In the modern territory of Italy the traces of Greek, Etruscan and most especially Roman settlements represent a diverse range of spatial types which require brief consideration as the precursors of the type of Italian piazza we are familiar with today. Although Roman thought and practice was closest chronologically and physically to Italian forms of urban space, the influence of these earlier civilizations as interpreted through the Roman experience was also significant. Greek cities have been the subject of diverse interpretations, yet the fundamental influence of Greek urban culture underpins subsequent Western society, and in particular rooted itself in the Italian consciousness, so that the echoes of independence and democracy were to re-emerge, after the destruction of Greek settlements or their appropriation by Roman conquest and subsequent decay, in the rhetoric of the medieval city state. While Greek political ideas had a difficult relationship with the increasingly centralized forms of Roman government, they provided the language by which later cities could express their systems of authority and representation. This was manifested in the abstract quality of the spatial continuum which related the cities to the features of their vivid and specific landscapes, Greek urban space being characterized as generously dynamic, this dominant mode for the public areas and temple precincts contrasting with the rational grid method attributed to Hippodamus of Miletus (Martienssen 1956; Scully 1969). Although Hippodamian influence has been observed in later Etruscan settlements, their principal cities were designed to be both rational and in accord with a religious interpretation of the cosmos (Scullard 1967; Haynes 2000; Torelli 2000). Roman colonial settlements have clear geometrical relationships inherited from Etruscan layouts which were the product of divinatory practices that embodied their belief in human dependence on the otherworldly. The rituals which the Etruscans pursued in the process of city founding were maintained by the Romans in the forms of an augury reflecting the celestial order on the terrestrial plane to determine a favourable site, the tracing of the principal streets (cardo and decumanus) and in the ploughing of a ritual furrow to establish the divinely protected boundary (Rykwert 1976: 65–68). Etruscan planning practices, both religious and rational, were adopted by Rome partly as a means of defining a distinct Italian character to their cities. Unlike the abstracted void-like quality of Greek space, the Etruscans placed great emphasis on surfaces, in particular surfaces which could be entered. In urban situations this reverence for the threshold conferred positive value on the exterior space adjacent to the elaborated entrance plane or portico. This close connection between building and immediate urban setting is a characteristic of Italian urban space which can be seen as an inheritance from Etruscan practice. Drawing on both Greek and Etruscan cultures, the Romans combined them to produce a distinct form of urban environment which prized the civic and military significance of the sacred public space.

1.1 Forum Romanum, Rome. A view from the floor of the forum towards the Capitoline hill, with the arches of the tabularium beneath the Palazzo del Senatorio, and the Arch of Septimius Severus to the right.

1.2 Forum Romanum, Rome. A view from the tabularium, with the columns of the Temple of Vespasian in the foreground and the portico of the Temple of Saturn to the right.

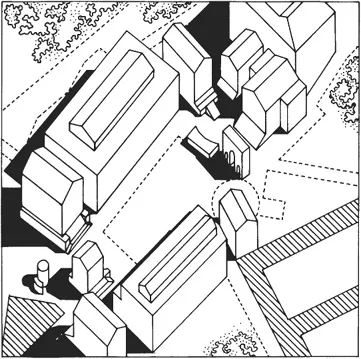

From these necessarily brief assertions it should be appreciated that there is an ambiguity about the purpose and methods of spatial composition in these cultures. Furthermore the typology of Roman urban space had two distinct forms which it is necessary to define. The first strand is related to the genius loci of Rome and the topography of the Forum Romanum itself, where the circumstances which produced the central political space of the entire empire presented itself as an ideal for emulation. The Forum Romanum, although developed as an accretion of disconnected structures, achieved an integration of those individual monuments into a unified though never fixed urban space. The second form is the result of the use of a generic model for city planning which related all colonial outposts to each other and by implication to the centre, the mother city. In some examples, though, the density of layering of distinct urban cultures is compactly expressed, as at Pompeii, where the Roman city concealed earlier Greek and Samnite settlements (Richardson 1988). Emerging from a lengthy process of archaeological excavation, the clear figure of the Forum of Pompeii represents a type of public space which is recognizable in numerous examples from later centuries as the Italian piazza, which merge generic and specific forms.

Favro (1996: 4–11) has discussed the perceptual reading of the urban environment by the Roman population, largely illiterate but nuanced in their understanding of the form of the city and the iconography of its meanings. Although we live in a visually saturated society, it is a literate one which expects communication through the written word, and occasionally has difficulty with the comprehension of the codes of symbolic imagery, beyond their immediate aesthetic appeal. We can only assume that the sturdiness of tufa or brick construction, the precision of travertine and the refinement of marble all communicated distinctions of prestige to the buildings and spaces which they were combined to create. Despite its cultural importance though, (the historical state of the centre of the Roman world in the era of its greatest activity during republican and imperial eras having long vanished), the Forum Romanum is difficult for us to fully appreciate since its present state is a figment of the early twentieth century imagination, and is fundamentally different from the situations which preceded it during the medieval, renaissance and baroque periods. As an urban experience it is a site which offers little explanation, confident of its own significance. And that confidence has been repaid by subsequent reinterpretations of the site itself and elsewhere as later public spaces sought to emulate the original model. The heterogeneous forms of the buildings which surrounded the Forum are its abiding legacy. The predominance of individual civic, religious or military structures and the proliferation of different expressions defining a precinct are the effects which have survived and continue to dominate, and which could also be seen as epitomising the Italian piazze which followed.

1.3 Diagram of the Forum Romanum with the Capitoline hill to the upper right. The new alignment of the later imperial fora is indicated at the bottom right.

The foundation legends of Rome played their part in the location of the Forum. The story of the birth of the semi-divine twins Romulus and Remus, and the former’s foundation of Rome in 753 B.C. was thoroughly documented by Roman authors. It combined Trojan origins, through the descent of the twins from Aeneas, and was therefore explicitly opposed through myth to Greek culture, but also featured Etruscan practice which made claim to native Italian origin. The inauguration of the city involved Romulus and Remus making rival auguries from the Aventine hill. Their observation of the flight of birds resulted in the settlement of the Palatine hill and its enclosure by a ritually defined wall. This legend found a comfortable fit with the context of the historic city itself, and there was therefore a mutual validation which took place between myth and actuality (Carandidni and Cappelli 2000). The settlement of the Palatine hill was safe from periodic inundation by the Tiber which formed a natural defensive barrier, but land on three sides of the hill (roughly on the north western, south western, and south eastern sides) was marshy and particularly prone to flooding. The north eastern side, however, was less vulnerable and bordered the area of rival settlements of the Sabines on the Quirinal and Esquiline hills, and was overlooked to the north by the double hill of the Capitol and the Arx. Thus, after its use as a burial ground by the neighbouring tribes and in fulfillment of the narrative provided by legend, topographic convenience was to lead to the development of this valley as the Forum Romanum, the accretion of monuments eventually obscuring its natural state (Grant 1970).

Returning to the tension between the generic and the specific, the Forum Romanum, as the centre of the ancient city, represented both a physical model for rivalry in other colonial cities and a conceptual model to which other fora in those subject cities referred by analogy (Vitruvius 1999: 64). The conceptual framework of the Roman city, the structure of cardo and decumanus crossing at the forum familiar from these colonial cities was however hard to discern in the physical and social centre of the Roman world. Attempts have been made to interpret the surviving topography of the city in the geometry of the ideal conceptualization but with little success, and despite the efforts of skilled interpreters of classical archaeology, most especially in the nineteenth century (Grimal [1954] 1983): 29; Salmon 2000: 98–106). The physical form of the forum was much more clearly influenced by the geometry produced by attention to the topographic features of the landscape. The difficulty of describing a simple geometric figure, reducing it to a single strong idea would not to the modern sensibility be considered a fault and yet one has only to consider the long history of the design of precisely symmetrical spaces to be aware that the pervasive association of ideal geometric space with political power was overturned in this particularly potent place and concept.

The actual space had a threefold purpose whose overlapping characteristics were at the root of its complexity. Firstly it was a religious place, the home of the city’s most sacred objects guarded by the Vestals. Secondly it was a political space, site of the meetings of the assembly in the Comitium, a vaguely circular open space overlooked by the Rostra adjacent to the Senate House. Beneath the Comitium, the so-called lapis niger was discovered, a Greek black marble pavement covering an earlier shrine the position of which emphasises the connections between the religious and political spheres. And lastly these roles were supported by the site’s military function, as the scene for the commemoration of victory through the erection of monuments, the celebration of triumphs and the holding of gladiatorial games on the pavement of the Forum. This tripartite function of worship, debate and expression of power was to survive into later Italian examples. In addition commercial life was also accommodated in the shops which lined the space and were later enclosed within the basilicas.

The pragmatic draining of the land for the Forum around 600 B.C., with the construction of the cloaca maxima (the great drain) and the paving of the ground surface, should not obscure the spiritual significance of its elements surrounding the most sacred site of the city. The Forum, arranged along the path of the via sacra, spanned between the two most important temples in Rome, that of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline hill (consecrated in 509 B.C. at the start of the republic), and that of Vesta on the valley floor itself (the present remains of which date from approximately 200 A.D.). Between these two poles, representing at one end an Etruscan legacy (with the celebrated pedimented temple, its gilded roof and sculptures), and at the other end the civic cult of Rome (in the eternal flame of Vesta, the hearth of the city in its circular temple the form of which recalled its original pastoral construction of willow and thatch), this urban space was loaded with political significance which established Rome’s right to pre-eminence. This meaning was reinforced by further limits to the space of the Forum which were established by two further temples, those of Saturn and Castor. Built at the foot of the Capitoline hill, and facing across the Forum to the Comitium the columns of the Temple of Saturn (rebuilt from 43 B.C.) survive to testify to its importance as both the state treasury and the site where laws were displayed. Adjacent to the complex of the Vestals, the Temple of Castor and Pollux was built on the site where the heavenly twins were believed to have appeared to water their horses at the pond of the lacus jaturnae, following the battle of Lacus Regillus in 499 B.C. The high podium of the Temple of Castor was used for balloting of the citizenry, and its three standing columns provide one of the great picturesque elements of the present-day archaeological site.

In the complex transition from republican to imperial systems of government the aesthetic contrast between these distinct elements was reduced by the creation of a series of three civic structures the consistent and repetitive treatment of which did much to unify the space. Straddling the saddle of the hill between the Capitol and the Arx, the Tabularium was an arcaded structure built from 78 B.C. to house the city records. The lower areas of this building survive as the foundation for Michelangelo’s Palazzo del Senatorio, the seat of contemporary Roman civic government which faces on to the Piazza del Campidoglio. The engaged columns and arcades of the Tabularium were complemented by the similar elevations of two buildings now vanished and the impact of which is harder to imagine, the Basilicas Aemilia and Julia, which functioned respectively as business and legal centres. The Basilica Aemilia was earlier in date, (179 B.C.) and it was this structure which was complemented across the Forum by Julius Caesar’s Basilica, completed under Augustus (54–46 B.C.). The remaining open side of the Forum was enclosed by the construction, also by Augustus, of the Temple of the Deified Julius (dedicated in 29 B.C.) adjacent to the Regia, his former residence as pontifex maximus (high priest) and the site of cremation of the assassinated dictator, with its own Rostrum facing the repositioned rostrum adjacent to the Comitium. The solar positioning of this new temple, and its alignment on a line between sunrise on the winter solstice and sunset on the summer solstice extended out to impose a new meaning on the circumstantially developed forum, but would perhaps remain obscure to other than the most informed citizen (McEwen 2003: 175–8). As the temple was so aligned that the sun entered the cella at sunset on the summer solstice, the centre of the Roman world was overlaid with a cosmological significance which associated the space with both Augustus’s adoptive father, Julius Caesar, and his reputed father, the sun god Apollo. The development of the Forum under Augustus, its gradual enclosure and visual homogenization brought about a reinterpretation of the space, so that in diametric opposition to its original orientation towards the Capitoline complex, new emphasis was placed on the other direction towards the Temple of the Deified Julius.

As the imperial system was consolidated the flight of significant daily activity to the new fora initiated under Caesar, Augustus, Vespasian, Nerva and Trajan emphasized the sacred aspects of the original Forum Romanum. New temples were dedicated to the deified members of imperial dynasties, and arches recorded their military triumphs. The Temple of Vespasian and Titus was constructed perpendicular to the Temple of Saturn and next to the Temple of Concord so that it faced along the Forum to the Temple of the Deified Julius and the Arch of Augustus at the other end. Three of its columns survive, but there are more complete remains in the elevated portico of the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina (built from 141 A.D.) facing across the Forum overlooking the Regia and the Temple of Vesta. Its subsequent life as the church of San Lorenzo in Miranda ensured the preservation of many of its elements. The Arch of Augustus (29 B.C.) which spanned between the Temples of Castor and the Deified Julius, which enclosed the southern corner of the Forum Romanum and acted as a screen to the Temple of Vesta, has not survived. More substantial is the Arch of Titus (81 A.D.) restored in the modern era and standing outside the Forum proper, positioned on the via sacra in relation to the House of the Vestals. However, within the Forum, b...