![]()

Chapter 1

Migrating Heritage

This chapter deals with the emergence of migrating heritage, the cooperation, networking and increasing convergence of memory institutions around cultural welfare, political narratives for Europe and emerging patterns in the changing landscape of cultural networks. It contextualises the diverse socio-cultural, historical and legal dimensions – at internal and inter-organisational level, within and beyond Europe – within which cultural institutions are striving to promote mutual understanding amongst individuals and communities of different cultures.

The Emergence of Migrating Heritage

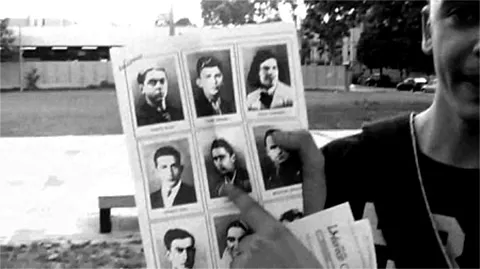

‘Noi siamo qua per testimoniare e ricordare’ (We are here to witness and to remember). These are among the opening words of a collaborative documentary (Figure 1.1) entitled Non vogliamo lavorare per la guerra (We don’t want to work for war). The documentary was produced in 2010 as part of an Italian local project led by the teacher Annalisa Govi and the historian Matthias Durchfeld. It was funded by the Department of Social Cohesion of the Municipality of Reggio Emilia, the Institute for the History of the Resistance and Contemporary Society of the Reggio Emilia Province (Istoreco) and the Permanent Territorial Centre of Reggio Emilia and Province (CTP). The project and the documentary narrate the stories of nine Italian workers, immigrants from other regions within Italy, killed on 28 July 1943 at the large industrial plant of Officine Reggiane (a producer of trains but also of weapons) while trying to reach a peaceful civil demonstration against the war. What makes this project extraordinary in my eyes is that these stories were shared with and absorbed by a group of European and extra-European immigrants in the process of learning Italian, in a project designed by an Italian and a German and supported by local institutions, one of which – Istoreco – collects and preserves an important historical archive. Nineteen people between 20 and 40 years old from Algeria, Austria, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, China, Egypt, Georgia, Ghana, Morocco, Nigeria, Russia and Sri Lanka took part in the project activities. These men and women were given the opportunity not only to learn about local history but to ‘adopt’ a story, actively and directly contributing to the transmission of memories from a state other than their country of origin, from a past which did not originally belong to them but which resonates with their own personal experience, a past which is often being neglected by younger generations of Italians. As remarked on in the documentary, if we live together in a place it is important that the memory – and I will add the identity – of that place belongs to all of us.

Figure 1.1 Non vogliamo lavorare per la guerra: a frame from the documentary

Source: Institute for the History of the Resistance and Contemporary Society of the Reggio Emilia Province (Istoreco), Italy

In a world increasingly characterized by mobility, travel and social networking (see Larsen, Urry and Axhausen 2006) this is one of many other examples in which history, heritage and memory can contribute to social inclusion, cultural dialogue and new forms of citizenship. What could be the cross-border heritage and memories of a heterogeneous and contested place such as Europe today? What kind of cultural identities can be welcomed in and across the European space? Which could be the institutional actors involved and how can they work together across borders and across domains? How can policy bodies support the contexts and practices necessary to encourage this?

We are witnessing a complex mixture of shift and continuities from the classic identity-marking heritage of European nation states (Macdonald 1993, Chambers 1994, Shore 2000, Orchard 2002, Sassatelli 2002, Macdonald 2003, Delanty 2003, Bennett 2009) to a contemporary migrating heritage, a new concept I have introduced in a previous edited volume (Innocenti 2014), and I am further exploring with this book. Cultural identities, which define what represents cultural heritage for us, are not written in stone but continuously evolve and reshape themselves, adapting to new contexts determined by contacts with our own and other cultures. Such encounters allow us to assess and to create our cultural identity. Therefore I believe that one key feature of (multi)cultural migrating heritage is the drive to unbind identities and let them interweave in new networks, in new pathways of exchange and hybridization. Migrating heritage encompasses and acknowledges the migration of post-colonial artefacts and also the migration and mobility of people, technologies and disciplines, crossing boundaries and joining forces in cultural networks to address emerging challenges of social inclusion and cultural dialogue, new models of cultural identity, citizenship and national belonging.

The increased permeability of borders in Europe is still mostly concerned with the shipping of goods rather than the migration of those perceived as alien outsiders, those not bringing income as do tourists or business people (Houtum and Naerssen 2002). Nevertheless, in this research I witnessed ferments of a new kind sprouting across Europe, contributing towards the potential creation of a more porous permeability and openness. These ferments reflect magmatic movements that are affecting the traditional roles of cultural institutions. For example, although they are so tied to the creation of institutional identities, museums and sites are no longer the only places in which identities are being performed and transformed. An array of cultural institutions – with public libraries on the frontline – is increasingly being pressured to take larger roles in welfare and social services (Aabø 2011). Cultural institutions are also engaging with socially controversial issues, some of which emerged within my research: for example the representation of ‘Islamic’ heritage in museums and online collections across Europe (Macdonald 2013, see also Macdonald 2014); how to address repatriation of human remains (Isnard and Galangau-Quérat 2014); how to include the issue of apartheid in the interpretative displays in science, technology and medicine museums (Messner 2014); how to address painful memories of British Children Migrant schemes (Tao 2014); how to present and address the cross-border, nomadic culture of Roma communities (Reynolds 2014). Cultural institutions are also more and more under financial pressure to join forces and converge to contribute to their sustainability. Finally, communication and information technologies have been bringing new possibilities and also new challenges to the world of cultural institutions. The use of digital technologies in particular is changing the dynamics and scope of cultural networking and of memory construction, display and understanding in a networked society (Castells 2010a, Castells 2010b, Castells 2010c, Castells 2010, Benkler 2006, Latour 2010).

I believe this offers the opportunity for contributing to the shaping of what Mark O’Neill has called ‘cultural welfare’ (O’Neill 2011 and 2014), not only at local but also at translocal and transnational level, and cultural networks can be instrumental in this process. How are cultural institutions – the historical collectors of cultural heritage, presenting collections to users within the frame of a systematic, continuous, organised knowledge structure (Carr 2003) – responding to such new scenarios? Cultural institutions typically address public knowledge and memory, and deal with the need to create a coherent narrative, a story of a society and its cultural, historical and social contexts. In recent decades, cultural networks have played an increasingly important role in supporting transnational, cross-sectoral cooperation and cultural dialogue, and creating cultural value. UNESCO’s notion of cultural diversity (UNESCO 2001) and the Council of Europe’s holistic definition of heritage (Council of Europe 2005) leave the dimension of interactions and exchanges between cultures to be further explored and defined, for example in terms of ‘cooperation capital’ as defined by the DIGICult project (European Commission 2002, 83–4). Furthermore, the idea of a network, or system of cooperation, between cultural institutions based on a non-territorial approach is an appealing way of questioning and breaking through Europe’s geographic, sociological and political borders, and a powerful way to represent migrant histories and routes. As the Dutch scholar of the geopolitics of borders, Hank van Houtum, has so aptly remarked:

We are not only victims of the border, but also the producers of it. Making a border, demarcating a line in space is a collaborative act. And so is the interpretation of it. The interpretation and meaning of borders is always open for reforms and transforms. De-bordering, searching for ways for a cross-border dialogue and using the public in between-spaces of the Interpolis/Cosmopolis is therefore also in our own hands. The world of tomorrow will have a different we, different barbarians, different here and there’s. In other words, a border is and can never be an answer. It is a question. The imperative geo-philosophical border question of our time is how and why we create a just border for ourselves and thereby for others. In this sense, we have all become borderlanders. (Houtum 2011)

A further dimension that calls for our attention is the possibility of moving the institutional focus and political discourse from the concept of ‘cultural diversity’ to that of ‘cultural similarity’, with the implications that this would bring. European collective cultural identity is constructed and fostered by the European Union via a dynamic, ongoing process of cultural policies and symbolic initiatives under the motto ‘United in diversity’, which has become the canonical frame of reference for European integration. The latest example of this is the European Heritage Label, an initiative appositely designed in 2011 to select heritage sites with a significantly symbolic role for European history and culture and to strengthen the support for a shared European identity and integration.

Verena Stolcke has argued that this has led to an increasing ‘cultural fundamentalism’ over the last decades, ‘a rhetoric of inclusion and exclusion that emphasis the distinctiveness of cultural identity traditions and heritage among groups and assumes the closure of this culture by territory’ (Stolcke 1995, 2). This cultural multiplicity needs to be operationally and practically implemented and supported, without being susceptible to self-referentiality and ghettoisation. Acknowledging various degrees of difference and at the same time uniting, both in cultural networks and in individual initiatives for cultural dialogue, could be achieved by focusing on similarities. In the words of writer, philosopher and librarian Sreten Ugričić:

Through discovering similarities a relation is established, relatedness is established, mutuality is established. Through discovering similarities closeness is established. Through discovering similarities kinship is established. Similarity means to make common, to communicate, to understand, to bring closer, to accept. Through discovery and recognition of similarities understanding is realised, communication is realised, trust is realised, solidarity is realised. (Ugričić 2012, 39)

At an institutional level, in its medium-term strategy for 2014–2021 UNESCO seems to have embraced a focus on similarity rather than diversity by stating that ‘cultural heritage is important to bring together people, communities and societies, by highlighting common ties and experiences and by providing places for dialogue, civic engagement and reconciliation’ (UNESCO 2013a, 33). In the following sections and throughout the book I explore these concepts further through a selection of concrete case studies.

Partnerships and Convergence of Memory Institutions for Cultural Welfare

In modern Western society, cultural institutions include but are not limited to libraries, archives and museums (Hjerppe 1994, Dempsey 1999), sometimes also jointly referred to as ‘LAMs’ (Zorich, Gunther and Erway 2008), galleries and other heritage and cultural organisations. Their histories are often intertwined, although their interrelations have not always led to a consolidated path of collaboration. For example, museums and libraries have developed separate institutional contexts and distinct cultures.

Jennifer Trant (2009) noted how the philosophies and policies of museums and libraries now reflect their different approaches to collecting, preserving, interpreting and providing access to objects in their care. At the same time, in terms of information policies and frameworks Trant notes a shift towards a progressive convergence of library, archival and museum studies. Liz Bishoff (2004, 35) has remarked:

Libraries believe in resource sharing, are committed to freely available information, value the preservation of collections, and focus on access to information. Museums believe in preservation of collections, often create their identity based on these collections, are committed to community education, and frequently operate in a strongly competitive environment.

In the twentieth century, policymakers and fund holders attempted to group and bridge these communities of practices through ‘their similar role as part of the informal educational structures supported by the public, and their common governance’ (Trant 2009, 369). Such commonalities are increasingly important to the sustainability of museums, libraries and related public cultural institutions in a globalised world. Within the context of this research, exploring the potential for partnerships between museums and libraries also provides the opportunity to critically reflect on the roles and power of both types of institution.

Museums are historically positioned to interpret and preserve a culturally diverse heritage, although until now they have typically selected and showcased the histories and collective memories of the elites rather than ethnic minorities, weaving them into the grand metanarratives of nation states (see for example Barker 1999, Karp et al. 2006, Knell, MacLeod and Watson 2007, Gonzalez 2008, Bennett 2009, Graham and Cook 2010). As centres for culture, information, learning and gathering, libraries would be natural service providers for a migrating heritage and culturally diverse, transnational communities, enabling intercultural dialogue and education while supporting and promoting diversity (IFLA 2006). But as sites of learning and knowledge, libraries are not neutral spaces (Chambers 2012).

Public libraries in particular are rooted in their locality, actively contribute to promoting citizenship and are increasingly engaged with social welfare activities, such as the Idea Stores (Chapter 4). Museums and libraries, joining forces with other cultural institutions such as cultural foundations and cultural associations, are in a position to become active protagonists for ‘cultural welfare’. In recent decades, national museums have begun to cautiously embrace a more inclusive approach, and non-national institutions such as anthropological and city museums have been leading the way towards inclusiveness. In the words of Mark O’Neil, Director of Policy and Research at Glasgow Life:

Given the deep layers of history in every inch of European land, how people form attachments to and understand the places where they live (whether they are recent arrivals or descendants of ancient residents) is important. The paradigmatic 19th-century museums were nationalistic – but numerically much more common were city museums, reflecting the huge growth through urbanisation. All these billions of new urban residents very rapidly developed attachments to their city – and donated collections to the museums. The city can be a strong site of inclusion, because city populations have always been more diverse. A lot of people experience continuity through their attachment to place, which can be harnessed easily to reactionary and prejudiced views – but this makes identifying progressive approaches to continuity and place important. (O’Neil 2014)

Collaboration between museums and libraries seem therefore a promising area in which to start identifying and problematising patterns and trends of partnerships. For example some studies of museum and library collaborations (for example, Diamant-Cohen and Sherman 2003, Gibson, Morris and Cleeve 2007, Zorich, Gunter and Erway 2008, Yarrow, Clubb and Draper 2008) have highlighted the benefits of joining forces and resources in a variety of areas.

The International Federation of Libraries Association (IFLA) has remarked that museums and libraries are often natural partners for collaboration and cooperation (Yarrow, Clubb and Draper 2008). One of the IFLA groups, Libraries, Archives, Museums, Monuments and Sites (LAMMS), unites the five international organisations for cultural heritage, IFLA (libraries), ICA (archives), ICOM (museums), ICOMOS (monuments and sites) and CCAAA (audiovisual archives), to intensify cooperation in areas of common interest. A study in the United States observed that ‘collaboration may enable […] museums and libraries to strengthen their public standing, improve their services and programs, and better meet the needs of a larger and more diverse cross-sections of learners’ (Institute of Museum and Library Services 2004, 9). The nature of this collaboration can be multifaceted and varied, and the terminology itself is interpreted with diverse meanings, in particular regarding the degree of intensity of the collaboration and its transformational capacity. Hannah Gibson, Anne Morris and Marigold Cleeve noted that ‘“library–museum collaboration” can be defined as the cooperation between a library and a museum, possibly involving other partners’ (Gibson, Morris and Cleeve 2007, 53). The authors use the term ‘collaboration’ with the meaning indicated by Betsy Diamant-Cohen and Dina Sherman, as ‘combining resources to create better programs while reducing expenses’ (Diamant-Cohen and Sherman 2003, 105).

A fruitful partnership and convergence between museums and libraries faces a number of challenges. Some authors have highlighted general risks and obstacles on the road to accomplishing successful collaborations between museums and libraries, with respec...