![]() PART I

PART I

The City Planned![]()

Chapter 1

Performing the Geographical Imaginary in Nineteenth-Century Pittsburgh

Michael R. Glass

Pennsylvania’s nineteenth-century state politics established the context for a burgeoning array of geographical imaginings in communities across the Commonwealth. Following an initially permissive attitude by the state toward the right of local communities to develop their own vision regarding land use and local identity, the period between the state Constitutional Conventions of 1837 and 1872–73 saw the rapid evolution of urban political geographies – notably in the city of Pittsburgh and the surrounding Allegheny County. Pittsburgh’s community leaders envisioned and codified the city in various ways: as an agrarian region, an industrial power, a bucolic suburbanizing city and as an exemplar of temperance. The codification of new urban political boundaries in Pittsburgh through the courts thus represent particular ‘performances’ wherein competing visions for new urban spaces occurred during a period when the state legislature unwittingly enabled the local experimentation with different forms of municipal government. This era of experimentation waned after the 1872–73 Constitutional Convention, as legislators sought to control an urban hierarchy characterized by a cacophony of geographic visions, which did not necessarily coincide with the state’s vision of a modernizing Pennsylvania.

The period of this case study demonstrates what can occur when the unleashing of community imaginations about their own geographies collides with non-local imaginings of the same. The prime example at the state scale was the unleashing of new geographic visions in 1834 with the legal devolution of municipal incorporation powers to the county scale, and the consequent tightening and redefinition by state politicians in 1872–73 over what constituted local political definitions of ‘city’, ‘town’, and ‘borough’. At the local scale, the devolution of incorporation powers enabled entrepreneurs to define their own spatial practices within geographic spaces which they constructed at the stroke of a pen. Such spatial representations of community ideas and ideals remain visible in historic maps of the city, and enable researchers to identify the dynamism and vigour with which urban communities developed new spatial practices and senses of the places they inhabited.

In the next section I discuss the urban experience in Pennsylvania, where different conceptions of urban space were attempted – from the official scale of the state, to the communities of practice, which sought to codify their own notions of land use. The years between 1837 and 1872–73 (the years of Pennsylvania’s two Constitutional Conventions) mattered greatly for the geographical imaginaries which occurred. I describe the performance of urban identity by local communities as geographical performances, and describe how Jacques Derrida’s concepts of iterability and citationality can be helpful in explaining the rupturing of spatial forms seen in Pittsburgh during the nineteenth century, and in the unceasing efforts of communities to shape and reshape new geographical imaginations as they search for the perfect performance of spatial form.

Pennsylvania’s Constitutional Conventions – Shaping the Urban Hierarchy

By the mid nineteenth century, a new phase of urban expansion had begun in the United States, requiring states to find new political methods for controlling and developing their territory.1 Whereas the original colonies (including Pennsylvania) derived their systems of government and land use from the English system, state-by-state approaches had begun to diverge by the nineteenth century, depending on local needs.2 Nevertheless, a common feature across the American states was the increasing prominence and significance of local governments, which gave rise to conflicts between localities (which claimed the rights to administer local affairs) and the states (which claimed the rights to supersede local authority). Such conflicts were exacerbated by local population growth, the state’s desire to connect territory by improving infrastructure, and the problems created by special-act charters. All these conditions created situations which eventually required judicial intervention.3

Pennsylvania followed the national trends in governance reform during 1820–74, with relations between the state and the municipalities shifting in accordance with the spatial and demographic changes characterizing the state during the nineteenth century. At the beginning of the period, state legislators did not need to exert much energy on the affairs of local municipalities given the sparse settlement across much of the state. The city of Philadelphia and the few other urban areas required some additional attention, but the main goal of the state legislature was to ensure that county-level government functions were adequate for handling administrative, judicial and police functions. As rural, urban and suburban worlds begun to emerge from formerly undifferentiated and natural spaces, the legislature needed to adapt to the diversifying landscape of the state. County courts were granted powers of incorporation in 1834, meaning that local communities could apply to create new minor civil divisions (townships, boroughs or cities) without the need to obtain state sanction. The 1838 Pennsylvania Constitution codified this stance, emphasizing the freedom of governments to conform to local conditions, and reasserting the long-established role of the county as an administrative proxy between local communities and the state.

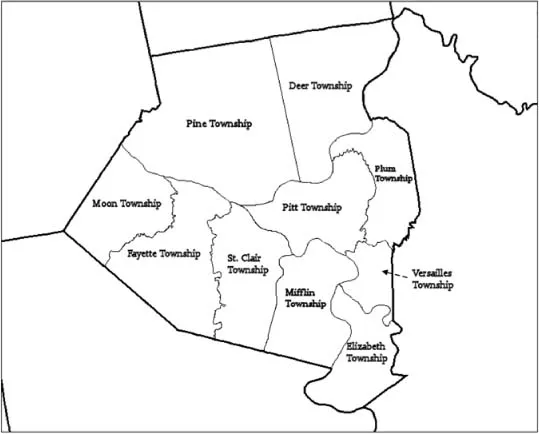

By the time of the 1837 Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention, the liberal attitude toward municipal incorporation had created a situation whereby the political map of the eighteenth-century city region was changing appreciably. In the south-western corner of the Commonwealth, Allegheny County’s original seven townships were fragmenting into multiple municipalities because communities demanded smaller political units which would (in theory) be more responsive to local needs.4 Whereas the county performed an essential intermediary role between local administrators and the state, community identity was performed at a more local scale – at a scale smaller than of the original townships, given the haste with which these began to fracture into new socio-political spaces, created at the behest of local communities. The eagerness to erect new townships suggests the desire to assert some greater degree of local identity, and also indicates unwillingness on the part of locals to be contentedly subsumed under a larger political unit created by the state legislature (and their local proxies) for administrative reasons.

Despite the activity in the formation of new political spaces across Pennsylvania after 1834, the state legislature’s attention seldom dipped below the county level between the Constitutional Conventions of 1837 and 1872–73, and legislators maintained a laissez-faire approach to local rights for self-government. For its part, the average Pennsylvania county of the mid nineteenth century lacked either the capacity or will to generate a regional identity which could direct local municipal affairs. In the early nineteenth century, the United States county was responsible for routine matters of governance such as tax assessment, rural policing, road administration and judicial affairs. None of these powers necessitated inter-governmental coordination, or strategic planning to the extent required of twenty-first century counties.5 State and county inattentiveness to local governance provided a fertile environment for the continual restructuring of social and political space by local leaders, entrepreneurs and communities who saw little utility in retaining the township lines inherited from the previous generations of settlers and surveyors (Figure 1.1). This context paved the way for local communities to conceive and perform distinct geographical imaginaries.

Figure 1.1 Allegheny county townships, 1800. © Michael R. Glass

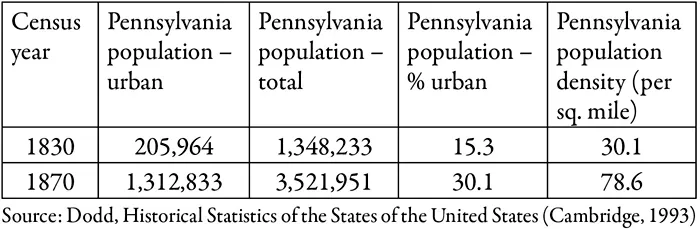

By the 1872–73 Constitutional Convention, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was becoming much more urbanized; 30.8 per cent of the population lived in urban areas in 1870, compared to 15.3 per cent at the time of the 1830 Census (Table 1.1). Urbanization was causing significant and rapid changes to the social and political composition of the state, and compelled the legislature to reconsider their role relative to local municipalities. Initial debates at the Constitutional Convention centred on the amount of latitude given to local communities in incorporating new urban charters. Since 1834, communities held the right to declare themselves cities based on simple majority votes of the local population and subsequent ratification by the county court. Whereas this had seemed appropriate in the earlier part of the nineteenth century, the increasingly complex urban landscape of Pennsylvania made this freedom of incorporation less appropriate in 1873, at least as far as state legislators were concerned.

Table 1.1 Pennsylvania population, 1830 and 1870

The essential concern among state-level politicians was the fear that they were losing control over Pennsylvania’s urban hierarchy. The influence of judicial rulings such as the ‘Dillon Rule’, which sided with the state when local powers were ambiguous, led to greater codification of municipal rights than had appeared in prior state constitutions. The problems of special-act legislation were also the subject of heated debates over the governance arrangements for Philadelphia, Pittsburgh and other cities in Pennsylvania.

The permissive attitude to municipal incorporation that the state had maintained since 1834 led to delegates raising strong objections at the 1872–73 Constitutional Convention, raising concerns over the potential for so-called abuse by small towns seeking the glory of a big-city charter. Article XV of the 1874 Pennsylvania Constitution concerned Cities and City Charters (Box 1.1). In its final form the article was restricted to two issues – when cities could be chartered and how debt could be contracted and repaid. However, the debates concerning this article had covered a much broader array of issues concerning urban governance, including why it was necessary to create a restrictive legal definition of the ‘city’, the amount of legislative autonomy local municipalities were to be granted, and the importance of the State Legislature retaining the flexibility to pass laws governing local areas.

During the initial debates, an early section stipulated that ‘[t]he Legislature shall pass general laws whereby a city may be established whenever a majority of the electors of any town or borough voting at any general election shall vote in favour of the same being established’. This formulation faced strong objections from delegates who were concerned that small towns would ‘abuse’ the ease with which they could attain a big-city charter. Mr Dodd, Delegate at Large from rural Venango County in north-west Pennsylvania, typified state opposition to this local power. Dodd warned that small towns would ignore the ‘cumbersome, useless and expensive’ nature of city charters when used to govern smaller communities. Dodd’s home county of Venango was replete with several small settlements with names such as Oil City. He argued that:

Box 1.1 The Pennsylvania Constitution, 1874. Article XV – Cities and City Charters

Section I: Cities may be chartered whenever a majority of the electors of any town or...