![]() PART I

PART I

Social-Psychological Advances in Music Education![]()

Chapter 1

Toward a Social-Psychological Model of Musical Ability1

Charles P. Schmidt

Introduction

Throughout its history, research in musical ability has been closely linked to developments within the broader field of psychology. Philosophical and methodological issues inherent in the work of Carl Seashore through that of Edwin Gordon can be seen as forming a microcosm of the psychometric traditions of intelligence and personality.

Current literature suggests parallel challenges to the fields of personality, intelligence, and music psychology. For example, a number of authors (e.g., Saklofske & Zeidner, 1995; Sternberg & Ruzgis, 1994) postulate that the historical distinction between research in intelligence and that in personality has been counterproductive and that a reunification is called for. A similar division has existed between research in musical ability and social psychology of music. On this point, Kemp (1996) has called for a broader perspective on musical ability—one that incorporates the “musical personality.”

Although Kemp’s review of the evidence supports the incorporation of personality factors in models of musical ability, related constructs of motivation, cognitive style, and affective variables are also germane. Hence, this chapter expands on Kemp’s argument by examining musical ability in the context of individual differences that extend beyond personality. In light of the evidence reviewed, a recent integrative model of intelligence and personality (Chiu, Hong, & Dweck, 1994) will be explored as to its implications for a social-psychological model of musical ability. The term musical ability will be construed broadly to include music aptitude and achievement (after Boyle, 1992).2 An overview of the literature concerning relations between musical ability and social-psychological constructs follows.

Kemp (1996) has summarized the evidence concerning the musical personality, particularly his own work with the Cattell Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire (PF16).3 His review indicates that the variables of androgyny4 and the Cattell factors of introversion, independence, sensitivity, and anxiety appear to discriminate between musicians and the general population. Kemp further profiles subgroups of musicians and suggests that personality may predict perseverance, vocational choice, and success in certain musical domains.

Some personality traits are more salient than others are in predicting performance on convergent5 musical tasks. Schleuter (1972) found nonsignificant relations among seventh graders’ scores on Cattell’s personality factors and Gordon’s (1965) Music Aptitude Profile (MAP), the only exception being the personality factor of intelligence. Thayer (1972), in contrast, found strong relations between the MAP, Gordon’s (1970) Iowa Tests of Music Literacy (ITML), and the Cattell factors of warmheartedness, intelligence, obedience, and tender-mindedness for seventh graders. Warmheartedness, obedience, and tendermindedness were correlated with most subtests of the Seashore Measures of Musical Talents (Seashore, Lewis, & Saetveit, 1956). For ninth graders, intelligence and tender-mindedness were significantly related to the MAP and ITML and only intelligence was related to the Seashore test. Somewhat similarly, Shuter (1974) found the Cattell factors of sensitivity and self-control to be related to elementary students’ scores on the bentley Measures of Music Abilities (1966). Disparities in results for the Cattell factors may be due to differences among the music tests, developmental differences, or both.

Personality has also been examined in divergent musical thinking. Hassler and Feil (1986) found a strong relation between androgyny and musical creativity for boys but a nonsignificant relation for girls. Swanner (1985), using a sample of third graders, found significant relations between Webster’s Measure of Creative Thinking in Music (MCTM) and Cattell’s factors of excitability, self-confidence, and anxiety. Notably, extraversion, aggressiveness, and independence were not significantly related to the MCTM. Another important finding is that relations between the MCTM and music aptitude have consistently been shown to be low or nonsignificant (Baltzer, 1989; Schmidt & Sinor, 1986; Swanner 1985; and Webster, 1983). Therefore, the fact that personality correlates of musical creativity differed from those revealed in the previously cited research for music aptitude may support the view that personality functions differently in divergent versus convergent musical thinking and by age.

Cognitive Styles

Cognitive styles can be placed at the interface between personality and intelligence. Whereas abilities focus on the questions of what and how much, cognitive styles pertain to the question of how. Styles define consistent individual differences in information processing that are aligned with personality tendencies, not predicted by intelligence.

In musical tasks, leveling-sharpening, reflection-impulsivity, and field dependence-independence (FDI) appear to be relevant.6 Sharpening has been found to be related to secondary-level students’ high scores on the MAP harmony and meter tests (Eastlund, 1990). Reflection has been significantly related to college nonmusic majors’ performance on the chord analysis task of the Wing Standardised Tests of Musical Intelligence (1961), and related to tonal memory scores on the MAP and Colwell’s (1969, 1970) Music Achievement Tests (MAT) (Heitland, 1982). Further, reflection has been related to second graders’ achievement on the tonal test of Gordon’s (1970) Primary Measures of Music Audiation (PMMA) but not to the PMMA-rhythm test or Webster’s MCTM (Schmidt & Sinor, 1986).

Among cognitive styles, field dependence-independence appears to have the most robust relationship with musical abilities. Field independence (FI) has been significantly related to higher scores on music aptitude measures among college nonmusic majors (Heitland, 1982) and eartraining skills among music majors (Osborne, 1988; Schmidt, 1984b). FI has also been correlated with college nonmusic majors’ texture discrimination (Ellis, 1995b; 1996), identification of form (Ellis & McCoy, 1990), and long-term memory for musical excerpts (Ellis, 1995a). For children, FI has been related to performance on musical conservation tasks (Matson, 1978), rhythm perception (Schmidt & Lewis, 1987), and musical creativity (Schmidt & Sinor, 1985). Further, FI has been related with superior sight-reading skills in secondary school instrumentalists (Ciepluch, 1988; King, 1983) and professional-level pianists (Kornicke, 1995).

Kornicke found that FI was significant for males but nonsignificant for females. Hence, field dependence-independence may interact with gender in predicting musical task performance. This hypothesis is supported further by data indicating that this variable correlated moderately highly with elementary- and secondary-level male subjects’ scores on musical creativity but that the correlation for females was markedly lower (Hassler & Feil, 1986). Together, the results seem to support admonitions that gender should be controlled for in studies of personality in general (Cattell, Eber, & Tatsuoka, 1970) and the musical personality in particular (Kemp, 1996).

Of the constructs discussed, field dependence-independence stands out as the one having the most replicable association with musical ability. In every study cited, FI related to better performance and this relation was stronger for those tasks requiring greater analysis, restructuring, and problem-solving abilities.

Motivation

Much of the recent motivation research in music has focused on students’ attributions of success and failure (see Asmus, 1994).7 Only one study (Asmus & Harrison, 1990) has examined attribution theory as it relates to musical task performance, and in that case, no significant relation was found. Locus of control (LOC)8 is related to attribution theory and may function in musical ability. Kornicke (1995) found external LOC (attributions due to luck, chance, or powerful others) to be a significant predictor of high sight-reading scores among advanced male pianists. Again, the need to control for gender is highlighted, as LOC was a nonsignificant predictor of sight-reading scores for female pianists.

Self-concept is a promising motivational variable in musical ability. Walker (1978) observed a significant relation between general self-concept and undergraduates’ achievement in the music curriculum, and Laycock (1993) found musical self-concept to be linked to the quality of high school students’ compositions. Just as important, self-concept as measured by Svengalis’s (1978) instrument explained up to 28 percent of the variance in fifth and sixth graders’ achievement on the MAT (Hedden, 1982).

Toward an Integrative Model

The cited evidence suggests the need to integrate social-psychological constructs within theories of musical ability. Using the Chiu et al. (1994) model as a point of departure, we can develop a similar framework for musical ability. My assumption is that issues surrounding intelligence and general ability are also operative in questions of musical ability. In this context, it is necessary to interpret personality processes in a broad sense—one that includes a range of individual difference variables.

Chiu et al. (1994) argue that a distinction between intelligence and personality makes sense “only when the psychological processes making up each construct are in their latent, inert form” (p. 104). They theorize that, whenever either set of processes is activated, intelligence and personality become intertwined and cannot be evaluated separately. Empirical support for such integration can be seen in psychological research (e.g., Niedenthal & Kitayama, 1994).

Chiu et al. outline three levels each for mental processes and personality processes. (Note that both the term level and the finite number of levels may be open to question but that these aspects are not requisite to the musical adaptation explored here.) The three mental processes are (1) Basic Mental Operations (e.g., attention, encoding, representation, transformation, metacognition); (2) Skills and Knowledge (i.e., declarative knowledge—including factual information, beliefs, and attitudes—procedural knowledge, and crystallized intelligence); and (3) Adaptive Behavior (i.e., processes that are brought to bear on problem-solving tasks in academic contexts). Adaptive behavior is defined as the extent to which the cognitive system makes full use of available information, functions to achieve goals, and meets the demands of a rapidly changing environment.

The three levels of personality are (1) Basic Motivational and Affective Processes (e.g., perception of social cues); (2) Knowledge Structures and Belief Systems (e.g., self-concept, self-efficacy, attributions of success/failure, standards, and values); and (3) Complex Patterns of Adaptive Behavior (in social contexts). The unevenness in quality of operational definitions for the constructs identified in the three personality levels is an acknowledged difficulty with the model.

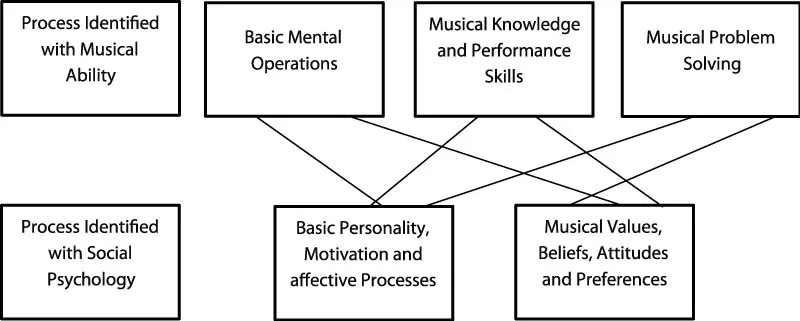

Figure 1.1 A Model for Social-Psychological Processes and Musical Ability

The working model for musical ability (see Figure 1.1) adapts and extends aspects of the Chiu et al. model. The proposed model assumes that when individuals are placed in musical situations that call for activation, such as making discriminations, performing, or solving problems, the lines between musical ability and social-psychological variables become blurred. Accordingly, musical information processing and performance are identified as manifestations of personality, motivation, cognitive style, and other affective variables.

The components of the preliminary model can be briefly traced as follows:

1. Basic mental operations of musical ability—These operations include aspects of auditory sensation, attention, perception, encoding in short-term memory, and representation/transformation in long-term memory. For musical abilities involving reading and perception of visual cues, we would also have to account for similar processes in the visual domain. Such development, however, lies beyond the scope of this chapter.

2. Musical knowledge and performance skills—This is a broad category that includes cognitive musical information and psychomotor skills derived from training and experience (i.e., declarative knowledge, crystallized intelligence, and procedural knowledge).

3. Adaptive problem-solving ability—In music, this category encompasses the ability to make full use of available information, to achieve goals, to adjust rapidly to incoming information, and to meet the demands of a changing environment. Hence, adaptive musical behavior involves fluid rather than crystallized intelligence and is central to successful performance in many musical tasks (e.g., improvisation). Adaptive problem solving is implicated in any perceptual or performance situation in which musicians must make continuous adjustments, such as intonation, balance, tempo, phrasing, and so forth.

The social-psychological variables in Figure 1.1 are grouped in two cells: (1) personality, cognitive style, and motivation variables, and (2) musical values, beliefs, attitudes, and preferences. The categories and variables listed are preliminary and are subject to revision based on additional empirical research. Given the literature reviewed, however, we can clearly see a number of variables that would be prime candidates for future investigation: (1) the personality variables of introversion, independence, sensitivity, anxiety, androgyny, intelligence, warmheartedness, obedience, tender-mindedness, excitability, self-confidence; (2) the cognitive-style variables of field dependence-independence, reflection-impulsivity, leveling-sharpening; and (3) the motivation variables of self-concept and locus of control. In light of the evidence cited, interactions of these variables with gender would also be included.

Chiu et al. (1994) broadly define their second personality cell as attitudes, beliefs, and values. In the music adaptation, it would follow that subjects’ attitudes toward music should supplement the constructs of self-efficacy and self-concept. Attitudes and beliefs about music as well as the musical self would be incorporated. Thus, affective and cognitive musical processes are viewed as mutually related. Musical ability and preference have been linked in LeBlanc’s (1987) theoretical model, and a moderately strong relation between the two variables has been shown in at least one study (Hicken, 1991). To date, the vast work in both music preference and musical ability, like intelligence and personality, has been carried out in isolation. It can be argued, however, that the boundary between the two areas has rendered an incomplete picture of musical ability.

The working model, while largely compatible with extant theories of musical ability (e.g., Webster, 1987) and music cognition (e.g., Davidson & Scripp, 1992), extends them by placing in the forefront an array of social-psychological variables that may explain variance across a range of tasks. These variables complement existing theories by accounting for other variables that mediate musical perception and performance.

Work toward refinement of this model would suggest several directions for future research in musical ability. First, consideration of tasks that extend beyond auditory short-term memory is necessary. Further possibilities for research include response latency, variation in the content and span of short- and long-term memory tasks, and division of attention. Moreover, interactions between task requirements and subject variables could become the focus of future study.

In conclusion, the purpose of the proposed model is to attempt to move toward a more unified framework for research in social psychology of music and musical ability. The full exploration of these ideas has yet to be accomplished, and it should be emphasized that the model sketched here is not free from difficulty. For instance, some components represent very broad ranges of processes (e.g., musical knowledge and performance skills), which require additional differentiation and refinement. Unevenness in reliability and validity for measures of some variables is also problematic. Some processes (e.g., auditory short-term memory) are well documented, but others (e.g., musical long-term memory) are less well documented. As for social-psychological variables, some (e.g., field dependence-independence) have consistent, strong support as predictors of musical ability, but others (e.g., LOC) have more tenuous backing. Some variables (e.g., introversion) have been found to distinguish musicians from nonmusicians but have yet to be linked with musical perception or performance. In terms of general approach, although highlighting the overlaps among cognitive, psychomotor, and social-psychological processes seems desirable from one point of view, such integration may appear overly reductionistic from another. Nevertheless, further refinement of the integrative model suggested here may help us to overcome tendencies toward fragmented and parochial research, formulate better hypotheses, and view musicality from a broader perspective.