![]()

Chapter 1

Risk Perception, Culture, and Legal Change

... toute société se construint d’elle-même et du monde visible et invisible une vision qui lui est spécifique, et de cette vision dépend le tracé des limites de la juridicité, dont le champ se confond partout avec ce qu’une société estime vital pour sa cohésion et sa reproduction.

N. Rouland, Anthropologie juridique, Paris, 1988, 400

The emergence in the 1990s of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad cow disease, has triggered a host of reactions worldwide. Far from being homogeneous, the responses have varied greatly, depending on which legal system is examined. Europe, Japan and the United States can be considered, among the industrialized nations, paradigms of the different approaches followed across the world. As we shall see in detail in the following chapters, the European Union and Japan have adopted a strong precautionary approach in coping with the crisis, not only implementing severe ad hoc measures to curb the spread of the epidemic, but also reforming the general framework governing food safety. This does not seem to be the case for the US, which has adopted less restrictive anti-BSE measures and no general food safety reform.

These heterogeneous reactions might appear strange. BSE represented in many respects the typical food safety crisis. The scientific uncertainties regarding the origin and consequences of the disease, the difficulties in singling out the agents responsible for the diffusion of the epidemic, the interaction between risk and media, are all elements to be found in most of food safety cases. Given these features and their homogeneity across the world, we might expect to have similar responses in the different countries. But, as noted, these expectations are frustrated. My goal is to investigate why the legal responses have varied so markedly across the legal systems of a host of industrialized countries. In doing so, different explanations will be examined, ranging from statistical evidence to economic considerations. But all these accounts fail in some respects to provide a complete picture. The impression is that a factor is missing from the overall picture: in my view, this factor is culture (Echols 2001: 13). Culture plays a pivotal role in shaping legal changes, but it is a paradigm often neglected in comparative legal analysis. This is the reason why, among possible, concurrent justifications, I chose to focus my attention on the role that culture occupies in the process of legal change. My goal is not limited to illustrating how culture molded the legal reforms which occurred in the aftermath of the mad cow crisis: I will also seek to underline the methodological importance that the study of the cultural context has in analyzing any process of legal change.

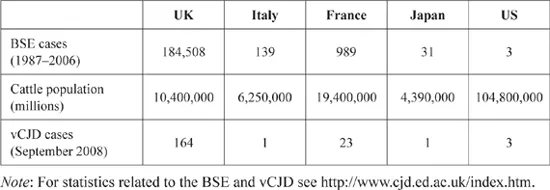

Before describing the role that culture played in the BSE case, other possible explanations must be analyzed. The first (and most obvious) explanation concerns the number of BSE cases which occurred in the three legal systems. BSE has been mainly a European affair. Most of the cases occurred in Europe, while only a tiny fraction were identified in the rest of the world. It seems natural that, in the geographical areas where the number of infected animals was particularly high, the BSE risk has been perceived as high. No wonder, then, that Europe has implemented far-reaching legal reforms to counteract the spread of mad cow disease. On the other hand, in a country such as the US, where only three cases of BSE have occurred up to now, the disease has not triggered the same reactions of fear that the Europeans have experienced.1 The lack of social alarm surrounding BSE did not generate the conditions for promoting legal reform of the food safety framework. Stated in general terms, reform would have occurred only in those countries where real problems in relation to BSE were present.

Despite the simple attractiveness of such an explanation, it seems to fail in many respects. First, it fails with regard to Japan, which has implemented comprehensive reform of its food safety framework in the wake of the mad cow crisis; nonetheless, in the years between 1987 and 2006, only 31 cases of BSE occurred in the country. The link between incidence of cases and legal reforms appears to be, therefore, particularly weak. Second, the link also seems dubious with regard to Europe. It should, indeed, be specified that most BSE cases occurred in one of the member states that form the European Union, namely, the United Kingdom. If we compare the number of BSE-infected animals in the years between 1987 and 2006 in the UK (184,508) with those in France (989) and Italy (139), we can note the huge gap in the incidence of cases (see Table 1.1).

BSE, thus, has been mainly a British affair, while the risk of infection in the other European countries has been limited, if not extremely low.2 This remark does not completely invalidate the link between statistical incidence and legal reforms, but poses some further doubts on its validity. It is true that the epidemic happening in one of the member states may have played some role in moving the European institutions to reform the supranational framework governing food safety. This might be particularly true in the agricultural sector, where integration is strong and the European Union plays a central role. But, on the other hand, there are plenty of cases where national crises have not triggered general reforms, such as occurred in the aftermath of the mad cow crisis. Ad hoc measures would probably have been sufficient to halt the spread of the disease from the UK to the other European countries. Therefore, the question regarding the reasons why BSE has triggered such reactions in Europe remains. It is evident that BSE has not been considered simply a national crisis, but something more. This points to the conclusion that the incidence of BSE cases played some role in the European context, and to a lesser extent also in the Japanese case: this is particularly true in the case of the UK, where the high number of BSE cases may have constituted an important engine for legal change. Nonetheless, the incidence factor cannot, per se, explain the quantity and quality of the reforms enacted.

Table 1.1 Comparison of BSE and variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (vCJD) cases in five countries

The second possible explanation concerns the ability of business operators and other pressure groups to influence the legal arena. Reference is made here to phenomena such as lobbying and agency capture. By lobbying, I mean the ability of pressure groups to influence political circuits in order to obtain legislation whose content is in line with the interests of the groups. “Agency capture” refers to the capacity of the industry to manipulate the decisions taken by the regulatory authorities, again with the aim of steering them towards the desired goals. In other words, the regulated capture the regulator. Theoretical analysis predicts that small, well-organized groups, with high stakes and enough resources will be highly effective in the lobbying or capture process (Stiglitz 2001; von Wangenheim 1999; Epstein, Halloran 1995; Niskanen 1994). It should be borne in mind, indeed, that both lobbying and agency capture are the products of a dynamic and competitive process, in which different interest groups struggle in order to influence the political or regulatory circuit (Becker 1983). The stronger the group (that is, with the features mentioned above), the higher the probability that it will be able to dominate in the competition with the other groups.

In the context of BSE, we might imagine that strong pressure groups have been able to influence the political arena, determining the enactment or the absence of legal reforms, depending on the legal system considered. More specifically, if this theoretical model were applied to the mad cow crisis, in the US we should find strong agricultural lobbies preventing any attempt to reform the food safety framework. Conversely, in Europe and Japan, consumer lobbies would have gained centre stage in the political arena, determining the wave of reforms I will describe in the next chapters. But there is only slim support for such an explanatory model.

With regard to the US, agricultural lobbies have been traditionally very important, both in Congress and at Agency level (Wolpe 1990; Wittenberg, Wittenberg 1989). Agricultural lobbies are among the major contributors in the fund-raising campaigns of many candidates in Congress, being at the same time able to gather many votes during elections (Browne 1988; Hansen 1991; Heinz et al. 1993; de Gorter, Swinnen 2002; Gawande 2005). This may explain why such lobbies are able to bring strong pressure to bear on the committees dealing with agricultural affairs, contributing to directing their political agendas.3 Similar comments can be made with regard to the influence that the farming industry, and the cattle lobbies in particular, have in the US Department of Agriculture (USDA; Nestle 2007, 2003; Schlosser 2005; Justice 2004; Rampton, Stauber 2004). Here we are more properly speaking of agency capture than of lobbying, even if there are many points of contact between the two phenomena. In both cases, indeed, the core feature is revealed by the ability of the pressure group to drive the political action of a public body, by molding the choices of the latter. In addition to the factors previously mentioned, another important element explaining the occurrence of agency capture relates to the closeness between the regulator and the regulated. The more an agency specializes in regulating a particular production sector, the closer will be the ties it has with the operators of that sector. This is particularly true in the case of the USDA (Casey 1998; Nestle 2003: 62 ff.). In this it differs, for example, from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which oversees different economic areas, whereas the USDA regulates a very specific field of the national economy, its competence being limited to the agriculture sector. Moreover, with regard to food safety, it has even more specific competences, since it is responsible only for the production and marketing of meat and poultry.

In such an environment, farm industries and the meat business are facilitated in advancing their requests, since they largely appear as the only counterparts in the regulatory process.4 It is not surprising that the USDA has been often criticized for being too sensitive to the interests of the industry. This remark finds support in the many delays and “softening” to which food safety reforms have been subjected in the history of the agency (Casey 1998: 150 ff.; McGarity 2005: 389–90). Thus, at first glance, the initial assertion that powerful lobbies could have prevented the enactment of legal reforms seems to find some support.

Nonetheless, the accuracy of this assertion is called into question if we compare the strength of the American agricultural lobbies to those existing in Europe and Japan. Europe also has strong pressure groups in this area (van Schendelen 1994; Pedler 2002). The so-called Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), an (anticompetitive) system of subsidies aimed at protecting the European agricultural market, is a good example of how lobbies have been able to shape public interventions in a way which conforms to their interests (Fennell 1997; Ritson, Harvey 1997; Ingersent, Rayner, Hine 1998; Howart 2000; Rickard 2000; Whetstone 2000; Baldwin, Wyplosz 2004: 229–30). In more recent times, the same lobbies have defeated most of the attempts to reform the CAP (Elliott, Heath 2000; Swinbank, Daugbjerg 2006). The very fact that the risks deriving from the BSE epidemic have been long downplayed within the European institutions depended, among other things, on the influence that interest groups had in the committees dealing with food safety and animal health matters.

Given the strength of the European lobbies, we should expect an outcome similar to the American one. But, as noted before, the amount and quality of the reforms enacted in the wake of the mad cow crisis show the industry groups’ inability to counteract the demand for changes. This remark also holds true in the light of the statistical evidence previously reported. An objection to our conclusion, indeed, would stress the fact that most of the BSE cases occurred in Europe, while in the US only three cases were reported. Hence it is natural that the European lobbies, faced with the vast scale of the epidemic, did not succeed in curbing the demand for reforms. But this contention does not take account of the fact that BSE has mostly been a British affair. Why were agricultural lobbies of countries other than the UK unable to counteract the reforms? Such reforms can be considered a burdensome onus for the food industry, imposing huge economic costs upon it.5 Indeed, in the first years following the appearance of mad cow disease, there was a tendency, supported both by the British government and by the competent European committees, to consider BSE exclusively as a British problem (Medina Ortega 1997; Krapohl, Zurek 2006).

In this way, lobbies have been able for some years to block attempts to reform the food safety system. The turning-point, after which pressure groups failed to counteract the demand for reforms, came when the BSE epidemic changed status, becoming a scandal.6

Similar considerations can be expressed with regard to Japan. In the Land of the Rising Sun, agricultural and cattle lobbies are also influential and have determined, over the years, the enactment by the government of protectionist policies in favor of the farmers (Bullock 1997; Mulgan 2005). Such an attitude has often triggered trade wars with other countries, which on several occasions have resulted in Japan being accused of distorting international competition (Davis 2003). The strong power which agricultural lobbies possess in the Japanese political arena is explained by their electoral weight. Farmers can be considered the main reserve of votes for the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), the electoral formation which has dominated in Japan almost without interruption since the end of World War II.7 But the strength of the agricultural lobbies also depends on the financial power that especially the main agricultural cooperative, Nokyo, was able to create over the years (Bullock 1997).

With specific regard to the cattle industry, there has traditionally been scant production of beef in Japan. The reasons for such meager production are due not only to the scarcity of land available for grazing, but also to historical and cultural reasons (Longworth 1983: 54 ff.; Cwiertka 2006: 24 ff.). The handling of meat was considered impure and those who carried out this activity were discriminated against. The discrimination they suffered, conversely, gave rise to the strong sense of community that in recent times still characterized the so-called “butchers’ guild” (Longworth 1983: 74). The closeness and isolation of the guild, on its own, have fostered the development of powers of control over the entire meat industry, with regard both to domestic production and the import of beef.

Thus, despite the economic marginality of meat production in Japan, the beef lobby has gained a major role in the political arena, at least with regard to the decisions regarding meat interests. This role has concerned not only the Japanese Parliament, but also the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries, which largely regulates the agricultural sector. In a system in which bureaucratic ranks are strictly intertwined with the industries, it is natural that public functionaries are particularly sensitive to the interests of the regulated.8

As in the European case, pressure groups in Japan have also had to surrender when confronted with the magnitude of the scandal triggered by the mad cow disease. The idea that the scandal has driven the reforms enacted in the wake of the BSE crisis, therefore, emerges further reinforced by the analysis of the Japanese experience. The only country where BSE has not become a scandal, that is, the US, also coincides, significantly, with a legal system where no noteworthy ref...