![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

‘Restrictive laws do not reduce the abortion rate they merely result in women dying’

Dr Dorothy Shaw

Women in the richer countries of the world have access to safe abortions either in their own countries or as with Ireland, in a nearby country. In contrast, women in the developing countries face unsafe operations. We can be grateful for the fact that abortion deaths have declined somewhat. In 2008 there were an estimated 47,000 abortion deaths which is a reduction from the 2003 figure of 56,000. Hopefully the growth in availability of misoprostol and mifepristone will further reduce the figure. However, we can still agree with the comments from an article published by the World Health Organization (WHO) that ‘Unsafe abortion remains one of the most neglected sexual and reproductive health problems’ (Grimes et al. 2006) This book aims to raise the importance of the issue and to propose measures to reduce the number of maternal deaths.

Latest figures indicate that nearly half the abortions in the world are unsafe and that nearly all (98 per cent) of unsafe abortions occur in the developing countries. In the developing world 56 per cent of abortions are unsafe compared with six per cent in the developed world (Guttmacher Institute 2013). The world figures showed a marked reduction in the incidence of abortions towards the beginning of the century. The number of abortions declined from 35 per 1,000 women of child bearing age in 1995 to 29 in 2003. However, by 2008 the rate had only fallen marginally to 28. The proportion of abortions that occur in the developing world increased between 1995–2008 from 78 per cent to 86 per cent. This was in part because the proportion of women living in the developing world increased. Consequently, while the number of abortions in the developed countries decreased by 600,000 between 2003–2008 in the developed world, they increased by 2.8 million in the developing world (Guttmacher Institute 2013). Apart from the women who die of abortion there are numerous others who suffer illness. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that around 20–30 per cent of women having an unsafe abortion suffer reproductive tract infections. The result is that around two per cent of women become infertile due to unsafe abortion and five per cent suffer chronic infection (Grimes et al. 2006).

In contrast to the situation in many of the poorer countries, legal abortion is now available in all industrialized countries except Ireland, Malta and Poland. National Health Insurance also covers the procedure in most industrialized countries. Abortion is still highly restricted in most countries of Latin America and Africa and in parts of Asia. Worldwide, the trend toward relaxing restrictions has continued.

Contraception

The Guttmacher Institute states that 215 million women worldwide are sexually active, do not want a pregnancy, but not using modern methods of contraception. It continued to say that making contraception available to all these women would only result in a cost of four billion dollars. This is roughly the cost of two weeks military operations in Afghanistan (Kristof 2012).

The concept of an unmet need for contraception has been used by the international population community since the 1960s. It developed out of surveys which showed education deficiencies with a great lack of knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) about contraception. The fertility surveys found a gap between what people knew their fertility preferences to be and their actions to achieve their desires. Further research in over 75 countries by the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) programmes provided further information. The unmet need for contraception is defined as the proportion of currently sexually active women who do not want any more children at present but are not using any form of family planning. There are a variety of reasons why women who do not wish to become pregnant nevertheless do not use contraception. These include opposition from sexual partner, concern about real or imagined side effects, lack of knowledge or lack of finance. When I conducted research into why women in the US, Ireland and the UK did not use contraception despite not wishing a pregnancy, I found the most quoted reasons for not use of contraception was ‘had intercourse unexpectedly’.

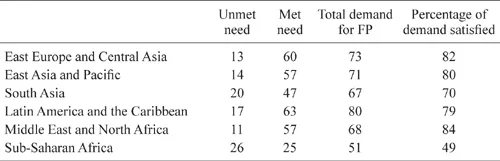

Table 1.1 Unmet need, met need and total demand for family planning (FP)

Source: World Bank 2013, p. 6. As this report is used so much it is not routinely referenced in subsequent chapters.

Using data from international surveys taken between 2000 and 2009 we can look at regional differences in met and unmet need for contraception.

The results show that sub-Saharan Africa has both the highest unmet need for contraception and the lowest percentage of the demand satisfied. This fact will account in part for the demand for abortion and also for the preparedness for good quality child care. In the forthcoming country by country analysis I include the data for the percentage of contraceptive prevalence for numerous countries. It is based on use of all methods traditional and modern. It identifies the percentage of women of reproductive age – here taken as 15–49 years and not 15–44 which is sometimes used especially for abortion analysis. It is measured for married women or those living with a partner (WHO 2012).

The Number of Abortions Safe and Unsafe

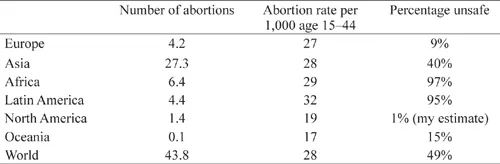

The number of abortions worldwide can be seen in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2 The number of abortions by region

Source: Sedge et al., Guttmacher Institute 2013. Figures refer to 2008.

The table shows the worldwide number of abortion is estimated at nearly 44 million. Which is a slight increase on figures for 2003 but below the estimates for 1995. The highest overall rate is in Latin America with a rate of 32/1000 women age 15–44 and the lowest is Oceania with an abortion rate of 17. The estimate is that the world rate is 28 per 1,000 and that 14 per 1,000 are safe and almost an equal number unsafe (also 14 per 1,000).

Amongst the developed countries there has been a fall in the number of abortions from 10.0 million in 1995 to 6.6 million in 2003 and 6.0 million in 2008. The rate per 1,000 women at risk (aged 15–44) has also declined from 39 in 1995 to 24 in 2008. This is almost a 40 per cent reduction.

Amongst the developing countries the situation is more blurred. The absolute number of abortions has increased from 35.5 million in 1995 to 37.8 million in 2008. However, this is largely due to growth in population and their abortion rate as measured per woman at risk shows a reduction from 34 per 1,000 in 1995 to 29 in 2008.

The regional analysis of the number of unsafe abortions shows that unsafe abortions are concentrated in Africa, Latin America and parts of Asia. The Asian figure would be much higher were it not for China.

Further investigation of the European situation reveals great differences which will be more fully discussed in the next chapter. In Western Europe the abortion rate is only 12/1,000. In Eastern Europe it is the very high figure of 43/1000 which is over three times the Western European level (Guttmacher Institute 2013)

The Pro-life Position

There are those who take the position that the law should proscribe abortion on the grounds that life begins at conception and that society should protect life. The major organizations will oppose abortion where a woman has been impregnated following rape. We shall see that these groups have had some success in maintaining restrictive laws especially in the poorer countries. However, there are a number of points to be made. First, life does not begin at conception. It begins before conception as it is necessary to have a live sperm and a live egg. A second point is that ‘pro-life’ groups are largely opposed to many pro-life activities such as artificial insemination by donor (AID) or in-vitro fertilization (IVF). These developments have helped thousands of women to have children they would otherwise have been denied.

A third important question is whether it is possible to legislate to create an abortion-free society. The country by country analysis in this book shows that in every country without legal abortion there is evidence of women having illegal and often unsafe abortions, or travelling to have abortions in a different country. Countries such as Holland and Switzerland have relatively few abortions by having good quality contraception.

Abortion is a reality

The fact that this book identifies abortion as being used by women in all countries suggests that it cannot be eliminated by authorities keeping it illegal. The implication is that governments can only pass laws which will decide whether abortions are safe and legal or unsafe and illegal. We will see that in countries such as the United States and Britain a great number of abortions occurred even when abortion was illegal. Dr Dorothy Shaw, the president of the International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) speaking at a WHO forum in December 2006, stated that evidence on sex and reproductive health ‘clearly shows the continuing track record of preventable deaths and illness in catastrophic numbers that would not be tolerated in most other imaginable situations’. She continued to say that sexual and reproductive rights are integral parts of basic human rights and that ‘restrictive laws do not reduce the abortion rate, they merely result in woman dying (WHO Forum 2006).

It is relatively rare for countries to legalize abortion and then to make it illegal. However, Romania provides an example of the problems that can follow. In 1965, it had a birth rate of 14.6 per thousand population and 64 abortion deaths. In 1966 it restricted abortion rights and access to contraception. The birth rate almost doubled to 27.4 in 1967 and the number of abortion deaths rose to 170 which is almost three times the 1965 level. Then, in subsequent years the number of abortion deaths continued to rise and were 364 in 1971 which is over five times its earlier level and the birth rate in that year was down to 19.1 and approaching its earlier level (Francome 1976).

If abortion is not readily and legally accessible, poorer women will be forced to seek treatment from local operators with potentially disastrous results. However, richer women will become abortion ‘tourists’. In the early part of the twentieth century British women went to France for abortions. When British law was changed French women began travelling to Britain in great numbers. In the early 1960s Swedish women went to Poland and women from the US went to Britain. After the legalization of abortion in New York in 1970, Canadian women went to the US. When financial restrictions were placed on poorer women in the US they began to travel to Mexico. German and Belgian women went to Holland until a change in their law. In Britain in 1972, over 50,000 women from overseas had abortions in the country and there was a spectacular growth in the number of Spanish women until its law changed. In 2006, Swedish operators expressed a willingness to help their Polish neighbours who had earlier helped their women obtain treatment. Irish women still travel to Britain, even from Northern Ireland where the 1967 Abortion Act does not apply. Over the years there have been distinct patterns where women travel abroad for abortions, but simultaneously, activists are working to change the law in their home country.

The International Conference on Population and Development of 1994 drew attention to the high levels of maternal mortality and a target was set to halve the 1990 rates by the year 2,000 and halve it again by the year 2015 (UN 2004).

Need for worldwide change

As recently as the 1960s there were only a few places in the world such as the Soviet Union which had liberal abortion laws. When the British Abortion Act 1967 came into operation on 27 April 1968 with no residential requirement, it meant that affluent women from all over the world could have access to safe legal abortions. It was followed by a great change in laws in other countries. In the period until 1982 twelve countries passed laws to allow abortion on request. These were Austria, Denmark, France, German Democratic Republic, Holland, Italy, Norway, Singapore, Slovenia, Sweden, Tunisia, United States and Yugoslavia.

In addition, 26 countries extended their grounds but did not officially give the right to choose. These were Australia, Belize, Canada, Chile, Cyprus, El Salvador, Fiji, Finland, Germany Federal Republic, Greece, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Iceland, India, Israel, Korea (Republic of), Kuwait, Luxembourg, Morocco, New Zealand, Peru, Seychelles, South Africa, United Arab Emirates and Zimbabwe. Chile and El Salvador have since eliminated all grounds for abortion and therefore move in the opposite direction.

Countries providing women with the right to choose, or at least obtain, abortion on a wide variety of grounds were predominantly the wealthier ones. In recent years there have been further changes. In 1995 the Beijing Platform for Action called on governments to rescind restrictive abortion laws that were punitive to women and from then until 2013, the following countries liberalized their laws: Albania (1996), Benin (2003), Bhutan (2004) Burkina Faso (1996), Cambodia (1997), Chad (2002), Columbia (2006), Ethiopia (2004), Guinea (2000), Guyana (1995), Mali (2002), Nepal (2002), Portugal (2007), St Lucia (2004), South Africa (1996), Swaziland (2005), Switzerland (2002) and Togo (2007) (Katzive 2007, Centre for Reproductive Rights 2007) Kenya (2010), Uruguay (2012), Ireland (marginally) (2013). In April 2007, Mexico City passed a law allowing abortion on request in the early part of pregnancy and Victoria State in Australia did so in 2008 (Henshaw, personal communication 2013).

Children Born into Poverty

There is a very high correlation with high family size and poverty for children. Niger is a good example. The country had the highest fertility rate in the world at 7.5 per woman (2011). It also has high infant mortality at 110 per 1,000 in 2011. This means that for every 100 fertile women in the country there will be an average of 825 infant deaths before the age of one year. Others will die later in childhood. The suffering that this waste of life causes can only be imagined as women and their partners are clearly unable to care for their children adequately. Furthermore, there will be many other children who survive, but who do so without proper nutrition, health and social care. The introduction of proper facilities for contraception and abortion, especially as part of a wider programme to improve medical and social support, could prevent much misery amongst poor women who have to face bringing children into the world without adequate resources.

Other countries are in a similar position. Women in Timor Leste, Afghanistan, Guinea-Bissau and Uganda all had an average family size of over seven children per woman during the period 2000–05. Other countries such as Mali, Burundi, Liberia, Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo had a fertility rate of over six children per woman. All these also have high rates of ill health amongst both women and children. Overall, in the poor countries 170 million children are underweight and over three million of these children die each year as a result (Wright 2006, p. 485). Access to modern contraceptives and abortion facilities are part of a wider need to improve maternal and children’s health We can see that things have improved, but there is still a long way to go.

International Developments in Aid for Family Planning

Official Norwegian development assistance began in 1952 and an emphasis on family planning followed in 1966. One point that was mentioned by experts was that population growth was hampering economic growth. In 1968 the Norwegian parliament decided that family planning should be a priority for development assistance. Norad, the government development agency allocated ten per cent of bilateral development assistance to family planning in 1970. In the following year parliament supported Norad’s policy proposal of placing family planning as part of primary care with the aim of helping to improve the health of women and their children (Austveg and Sundby 2005). The importance of contraception and reproductive health to development was also recognized in 1989 at a conference in Amsterdam, which placed as a target developed countries providing four per cent of their Overseas Development Aid to population activities.

At the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, Norway produced a report stressing ‘the seriousness of present population growth and the need to counteract the negative effects on the environment’. According to Population Action International, Norway was the only country before 1994 to allocate at least four per cent of overseas development assistance to population. Norway has been one of the largest donors to UNFPA since its inception in 1969 and also a large donor to IPPF. Overall, the proportion of family planning aid in 2004 for all donors was 5.5 per cent and so the 1994 target has been achieved. However, in 2004 in several countries the percentage was below two per cent. These were Austria (0.5 per cent), Italy (1.0 per cent), Greece (1.4 per cent), Spain (1.5 per cent) and Germany (1.9 per cent). So improved contributions from these countries would be useful in an area where funds are short. Countries above the five per cent level included Netherlands (10.2 per cent) US (9.2 per cent) UK (8.4 per cent) and Sweden (7.2 per cent).

The 1994 ICPD in Cairo led to the first major international agreement on unsafe abortion with 180 countries agreeing a programme of action. Its proposals fell short of deciding that a woman should have the right to choose in the early months of pregnancy. However, it drew attention to the public impact of unsafe abortion and the need to expand family planning services to reduce the recourse to abortion. In paragraph 7.2 it stated:

Reproductive rights … rest on the recognition of the basic right of all couples and individuals to decide freely and responsibly the number, spacing and timing of their children and to have the information and means to do so, and the right to attain the highest standard of sexual and reproductive health. It also includes their right to make decisions concerning reproduction free of discrimination, coercion and violence, as expressed in human rights documents. (Hessini 2005)

Hessini assessed how the principles and recommendations of the conference have been applied to increasing women’s access to ‘affordable, safe and legal abortion services’ in the decade until 2004. She asserted that studies have increased the knowledge of the magnitude of unsafe abortion, that they have raised the awareness of women’s experience of illegal abortion and linked it to other public health and women’s rights issues. This drew attention to the fact that there have been several studies of abortion complications. For example, one study estimated that over 20,000 women were being treated for abortion-related illness in Kenyan public hospitals. We will be providing similar evidence from a variety of countries.

It also stated that women still face numerous barriers in countries where abortion is legal. For example, in India where abortion has been legal for over thirty years, 76 per cent of fac...