![]() PART I

PART I

Historial and Cultural Perspectives![]()

Chapter 1

History Builds the Town: On the Uses of History in Twentieth-century City Planning

Michael Hebbert and Wolfgang Sonne

Michael Hebbert is an historian, geographer and town planner. He teaches town planning at the University of Manchester (England), edits the Elsevier research journal Progress in Planning and is active with the Urban Design Group and the journal Municipal Engineer. He works for the preservation of Manchester’s industrial heritage and has published widely on regionalism, urbanism, planning history, and London past and present.

Wolfgang Sonne is lecturer for history and theory of architecture at the Department of Architecture at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow (Scotland). He studied art history and archaeology in Munich Paris and Berlin and holds a PhD from the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule in Zurich. He has previously taught at the ETH Zurich, at Harvard University and at the Universität in Vienna. His publications include: Representing the State. Capital City Planning in the Early Twentieth Century, Munich, London and New York: Prestel 2003.

Modern urbanism has been profoundly shaped by readings of the past. Town planning is a prospective activity by definition, but its intractable, long-lasting subject-matter forces planners to take a stance towards the history, whether they cling to legacies, memories and precedents or reject them. In the words of Arthur Korn, one of the most outright rejectionists, History Builds the Town.1 In this paper we ask in what sense history built the twentieth century town. What types of historical reference have planners employed? Have they been actively researched and procured, or worn more casually, as loose-fitting myths? Which has counted for more, the particular or the universal?

Awareness of designers’ historiographic strategies is well developed in architectural theory.2 The uses of history in town planning have been less well studied. We argue that they fall into three distinct categories: first of all, history has been used as the encyclopaedic source of types and references; second, as the reservoir of collective memory, place-identity and local attachment; and third, as a source of normative justification and purpose for the act of planning. Each type of discourse implies a distinct time pattern and reading of the past. The balance between these modes has shifted in unexpected ways, and each has its risks. A planner with a one-sided sense of history is almost as dangerous as one with none at all.

Lasting Types and Forms

Modern town planning originates at the turn of the twentieth century, at the moment of shock when new technologies began to demonstrate their power to dissolve conventional conceptions of space and time. For those wrestling with this challenge, the first reaction was to look to a timeless formalism.3 Daniel Hudson Burnham and Edward Herbert Bennett begin their 1909 planning report on Chicago not with statistical data on the modern city but with a general history of classical urban design from Antiquity to the Beaux-Arts.4 Henry Aldridge opened his Case for Town Planning. A practical manual for the use of councillors, officers and others engaged in the preparation of town planning schemes (1915) with a hundred page account of planning as ‘one of the oldest of the arts evolved in the slow development of organised civic life in civilised countries’.5

In his seminal text for the new discipline, Town Planning in Practice (1909), Raymond Unwin emphasised the need for systematic historical research towards a ‘classification of the different types of plan which have been evolved in the course of natural growth or have been designed at different periods by human art’.6 His mentor in this project was the architect Camillo Sitte whose 1889 pamphlet Der Städtebau nach seinen künstlerischen Grundsätzen tried to distill lasting rules of urban design from examination of historic layouts. Sitte deliberately used black and white plan analysis in an attempt to abstract from context and derive generic principles for present practice.7

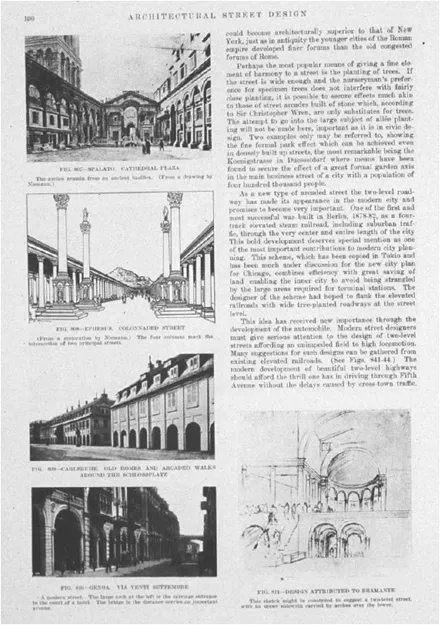

It was striking how scholars in the German art-historical tradition brought their discipline’s scholarly traditions of periodisation and abstraction of types and forms to bear on the design of cities, largest of human artefacts. Albert Erich Brinckmann wrote both on the design of squares (1908) and on town planning in general (1920).8Cornelius Gurlitt’s copious historical writing was matched by a manual of urban design in 1920.9 The most ambitious compendium combined Germanic formalism with American pragmatism. Werner Hegemann’s and Elbert Peets’ American Vitruvius: An Architects’ Handbook of Civic Art (1922) drew examples from 3,000 years of urban history with more than 1,200 illustrations.10 Historic variety was ordered according to universal urban elements, creating subtle thematic connections across long periods.

Figure 1.1 Werner Hegemann and Elbert Peets, The American Vitruvius, 1922. Arcades and colonnades are arranged in a historic sequence which suggests the eternal recurrence of urban archetypes.

Source: Werner Hegemann and Ebert Peets, The American Vitruvius. An Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art (New York: Architectural Book Publishing, 1922).

This way of constructing the affiliation of motifs resembled Aby Warburg’s contemporanous attempts to classify the painted antique pathos formula in the large tables of his ‘Mnemosyne-Atlas’.11 Hegemann and Peets were not writing an account of real historic influences or trying to conjure a return of archaic forms, but offering contemporary designers an encyclopedic scheme of urban elements, with a clear preference for a timeless classicism of axial layout and rhythmic enclosure.12

This claim for the universality of Civic Art was compromised once Le Corbusier and the Charter of Athens had explicitly jettisoned all historic types and forms in favour of a radically new and puritan urbanism, based upon the functional logic of the modern city. But it soon became apparent to town planners that their clients expected them to inject some humanism into the austere doctrine of functional separation set out in the Charter of Athens. The issue of human association dominated postwar meetings of CIAM, caused the breakaway of younger modernists in Team X in 1953, and triggered the emergence of the subdiscipline of urban design in 1956. The search for the heart of the city, its symbolic and interactive essence, brought modernism back to the interrogation of history.13

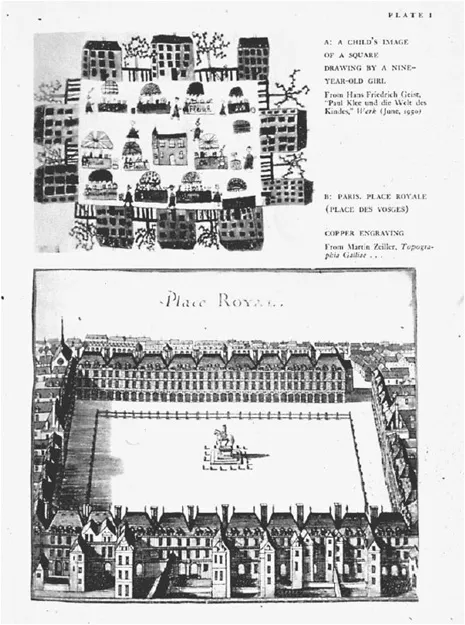

Figure 1.2 Paul Zucker, The archetype of a square in a children’s drawing and the Place Henri IV in Paris, in Town and Square, 1959. The eternal type of an urban element is represented by the ‘innocent hand’ of a child.

Source: Paul Zucker, Town and Square. From the Agora to the Village Green (New York and London: Columbia University Press 1959).

Kevin Lynch and Edmund Bacon defined urban design in terms of the analysis of historic streets and quarters, reestablishing the seminal importance of a Grand Tour of Italian exemplars.14 Joseph Rykwert went further back, looking to ancient Rome for source of symbolic meaning in urban design.15 At MIT, Stanford Anderson initated a major study into the history of streets and their dual generic role as a basis of circulation and a setting for exchange.16 And, in an early and ambitious contribution, Paul Zucker studied the history of the urban square, showing it to be a psychologically determined archetype of universal relevance at every stage of development and every scale of settlement. In his opening pair of illustrations a child’s drawing reveals the Ur-form of a square which also informed in Henri IV’s Place Royale in Paris.

The ‘Paradox of History’, for Zucker, was that types and forms could remain constant however radically functions change over the epochs of urban history.17

Towards the close of the century the broad current of postmodern urbanism became increasingly receptive to historical material that could inform revivalism. There were synoptic narratives such as the huge pictorial atlas of Leonardo Benevolo’s Storia della città and the encyclopedic multivolume Storia dell’urbanistica,18 and a revival in art-historical contributions such as Wolfgang Braunfels’ Abendländische Stadtbaukunst and Michael Hesse’s overview of Stadtarchitektur.19 Spiro Kostof, another architectural historian, contributed the most subtle and wide-ranging study of historic types and form in his final pair of books The City Shaped and The City Assembled.20 Like in the American Vitruvius from the 1920s, the structure was thematic, not chronological, deliberately inviting the modern practitioner to reflect and translate. In these years practising urbanists contributed actively to historical investigation. Rob Krier’s teaching and practice in Stuttgart gave rise to his study of generic types of street and block pattern,21 Phillipe Panerai and fellow members of the Versailles school produced their seminal analysis of the transition from nineteenth to twentieth century urban form,22 and Allan Jacobs contributed meticulously researched typologies of urban thoroughfares.23

For the neo-traditionalist wing the revival of historic types and forms became a matter of doctrine. Advocacy of street and square got entangled in arguments for masonry and timber building, vertical windows, and adherence to norms of classical detailing. Leon Krier was a polemical advocate of eternal principles of urban design, to which all good cities must conform.24 The wit and elegance of his work made up for the narrowness of its frame of reference. A more synoptic attempt to distill a systematic theory of urbanism from past types was the New Civic Art. Elements of Town Planning compiled by Andres Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk and Robert Alminana in 2003. Title and organisation pay deliberate homage to Hegemann’s and Peets’ American Vitruvius. An Architect’s Handbook of Civic Art (1922). In terms of its display as well as its contents the New Civic Art is anything but new – following established ...