![]() PART 1

PART 1

Critical Essays![]()

Chapter 1

Roxolana in Europe1

Galina Yermolenko

Roxolana in Western Europe

Rumors about Roxolana reached Europe some time by the late 1520s or 1530s, and certainly after her marriage to Suleiman in 1533 or 1534, which shocked both the Turkish and the European public.2 The chronicles of the Italian humanist historian Paolo Giovio, such as Turcicorum rerum commentarius (Parisiis, 1531, 1538, 1539) and Historiarum sui tempores (1552), published in several European languages and particularly well known in numerous French translations and editions,3 introduced to the western public the main players at the Ottoman court: Sultan Suleiman, his mother, “Rossa,” and Ibrahim “Bassa.” Giovio linked Roxolana to the 1536 execution of the Grand Vizier Ibrahim, stating that she hated Ibrahim for his opposition to her attempts to procure the throne for her son Bayezid (Bajazet).4 This story, single-handedly invented by Giovio, was later appropriated by other European historians and chroniclers.5

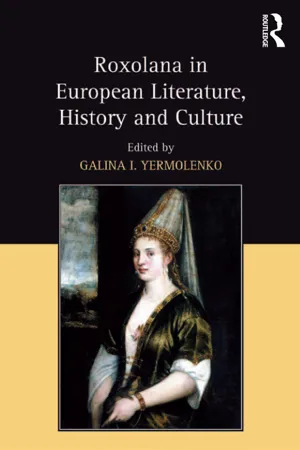

By the mid-sixteenth century, there appeared western European imagined “portraits” of Roxolana. According to some sources, Venetians habitually decorated the walls of their palaces with such imaginary portraits of “la sultana Rossa.”6 Among these was “La Sultana Rossa” featured on the cover of the present volume. This oil painting (ca. 1552) is attributed to Titian or Titian’s school,7 and is presently located at The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida, but it was originally owned by the Ricardi family in Florence.8 Other early modern oils, drawings, and engravings portraying “Rossa Solymanni Vxor” [‘Rossa Solyman’s Wife’] are held in the museums of Florence, Vienna, London, and Paris. None of these portraits is believed to have been done from live Hurrem, as strangers were usually not allowed to see or to communicate with the imperial harem women. Some of these portraits may have been based on original Italian medals; others depicted imaginary beautiful women in exotic costumes. Yet such pictorial representations of Roxolana clearly indicated an interest toward the powerful sultana on the part of the early modern European public.

But it was the shocking news of the 1553 execution of Prince Mustapha (the conventional western spelling of the Turkish name “Mustafa”) that made Roxolana a notoriously fascinating figure in the early modern West. Through the reports of western diplomats at the Sublime Porte, travelers to Turkey, and escaped captives, the news quickly reached the European continent. One source in particular played crucial role in disseminating the Mustapha story around Europe—Soltani Solymanni horrendum facinus in proprium filium, by Nicholas de Moffan, a Burgundian noble and erstwhile Turkish captive and prisoner.9 Moffan put the wicked Roxolana (Rosa), whom he called the “vngratious,” “deuilishe,” and “pestilent” woman,10 at the very center of the intrigue against Mustapha, accusing her of poisoning Suleiman’s (Solyman’s) mind with female artifices and sorcery. Moffan vividly described how the Sultan was watching the strangulation of Mustapha from behind a veil and even encouraged the mutes to finish off the resisting prince promptly, and how Gianger (Jihangir) stabbed himself to death out of sorrow.11

To demonstrate Rosa’s destructive effect on and abuse of the Ottoman laws, Moffan also recounted a story of how she tricked Solyman into marriage. She approached a Mufti (a chief Muslim juror) with a question of whether her erecting a mosque and a hospital for pilgrims would be profitable for her salvation. The Mufti replied that as the Sultan’s bondwoman (that is, his property), she would not be credited with all her good deeds; they would rather be credited to her master. At this reply, Rosa fell into sorrow, and was soon manumitted by the besotted Sultan. Rosa’s next trick was to refuse the Sultan physical intimacy on the grounds that as a free woman, possessing free will, she would be committing a carnal sin by going to bed with a man. This rebuff added more fuel to Soliman’s burning passion for Rosa, and he married her in violation of the Ottoman tradition.12

Moffan’s pamphlet became an instant hit; it was immediately reprinted by major European presses and translated into major European languages.13 Equally influential in propagating the Mustapha drama, and hence the negative image of Roxolana, around Europe in the later sixteenth century were The Turkish Letters of Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq.14 Although Busbecq’s letters, eloquently written and replete with his erudite comments and sharp observations, were a far cry from Moffan’s misogynist diatribe, they uncritically transmitted to the West the Ottoman rumors about Roxolana’s witchcraft and her vicious plot against Mustapha.15 Busbecq’s Turkish Letters were repeatedly reprinted and translated into several European languages in the course of the seventeenth century due to their enormous popularity with the European public.16

The Mustapha story shook the Western world to the ground and became one of the biggest sensations of the early modern age. It was retold and dramatized, often with embellishments and juicy details, in countless compilations—the Annales, Chronicles, Histories, Vitae, Vies, and Lives of illustrious ancient and modern people, styled after Plutarch’s Lives—that widely circulated around the European continent in various editions and languages. Among such works were the French “continuations” and revisions of Paolo Giovio’s chronicles (Histoires de Paolo Jovio, 1561, 1570, 1581)17; Bartholomaeus Georgievic’s De origine imperii Tvrcorvm (1560; 1562); Hugh Goughe’s The offspring of the House of Ottomano (1569/1570); Philipp Lonicer’s Chronicorvm tvrcicorvm (1578; 1584); André Thevet’s Les vrais povrtraits et vies des hommes illvstres (1584); Johannes Leunclavius’s Annales svltanorvm Othamanidarvm (1588; 1596); Jean-Jacques Boissard’s Vitae et icones svltanorvm Tvrcicorvm (1596); Richard Knolles’s The Generall Historie of the Turkes (1603); and Michel Baudier’s Inventaire de l’histoire generale des Tvrcs (1617). Through these works, “Rossa” and “Roxolana” became household names across the European continent.

Suleiman’s execution of Mustapha became an ultra-popular topic in sixteenth-and seventeenth-century European drama, spawning numerous French, Italian, and English tragedies: Gabriel Bounin’s La Soltane (1561); anonymous Solymannidae Tragoedia (1581); Georges Thilloys’s Solyman II (staged in 1608; published in 1617); Fulke Greville’s The Tragedy of Mustapha (1609); Prospero Bonarelli’s Il Solimano (1620); Antonio Cospi’s Il Mustafa (1636); Jean de Mairet’s Le Grand et Dernier Solyman ou la mort de Mustapha (1635); and Roger Boyle, Earl of Orrery’s The Tragedy of Mustapha (1668).

The fascination with this matter, with an added interest in the fate of Mustapha’s hunchback hal -brother, Jihangir (Cihangir, Gianger, Giangir, Zanger, Zeangir), continued well into the eighteenth century, in the tragedies of François Belin (Mustapha et Zéangir, 1705), David Mallet (Mustapha, 1739), Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (Giangir oder der verschmähte Thron, unfinished fragment, 1748), Christian Weisse (Mustapha und Zeangir, 1761), Sebastien-Roch-Nicolas Chamfort (Mustapha et Zéangir, 1778), and Louis-Jean-Baptiste de Maisonneuve (Roxelane et Mustapha, 1785).18 Even the eighteenth-century European opera took an interest in the Mustapha story, as can be seen from Johann Hasse’s Solimano (Dresden, 1753) and David Perez’s Solimano (Lisbon, 1757; revived in 1768).

The interest in the Mustapha story reflected the West’s fear of and fascination with the Ottoman Empire, feeding into the stereotypical images of the “cruel Turk” and the “lascivious Turk” that Europe conjured up in response to the Ottoman practices of fratricide (the custom of executing all the brothers and half brothers of a new sultan to prevent feuds between them) and polygamy.19 Suleiman’s violent act against his own son and his excessive love for Roxolana gave the western world an opportunity to moralize on the tyrannical nature of the Ottoman system.

The issues of dynastic legitimacy and monarchic power were of paramount importance for the West, where several European cour...