![]()

Chapter 1

The Unreadable Pleasures of Ladies Almanack

And speaking of women, dear sister, was there ever a woman made a good convert? (Ryder, p. 73)

Trying to persuade Richard Aldington to publish Djuna Barnes’s Ladies Almanack, Natalie Clifford Barney writes: ‘All ladies fit to figure in such an almanack should of course be eager to have a copy, and all gentlemen disapproving of them. Then the public might, with a little judicious treatment, include those lingering on the border of such islands and those eager to be ferried across.’1

Ladies Almanack is, possibly more than any other text by Barnes, a book that plays with secrecy but resists disclosure. Barney’s letter indicates a close club policy, the ability to rouse a gentlemanly voyeuristic disapproval, and the possibility of converting both those ‘lingering on the borders’ and those eager to be ‘ferried across’ this titillating Acheron. The dynamic between public and coterie is figured in this island where the pleasure of reading and the ‘délices de caste’ meet.2 The narcissistic and voyeuristic pleasures promised by Ladies Almanack are, according to Barney’s letter, both exclusive and potentially open to everyone willing; they can be experienced in different ways according to the reader’s geographical location on this mythical map.

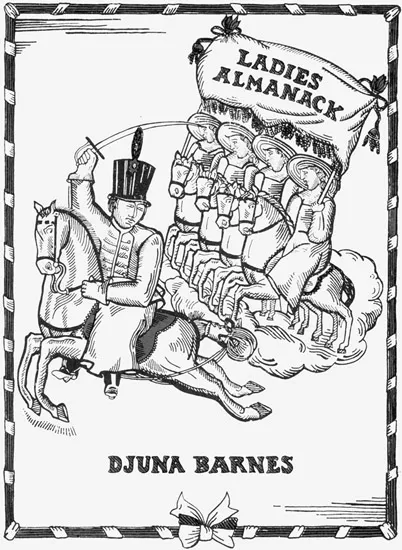

Privately printed with the financial help of Robert McAlmon at the Darantière Press of Dijon (like Ulysses), the volume came out in 1928, the same year as Ryder and what can be regarded as the alternative annus mirabilis of modernism, which also saw the publication of Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, and Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness.3 Barnes illustrated it herself and hand-coloured with Tylia Perlmutter 50 of the 1,050 copies.4

Fig. 1.1 Front cover, Ladies Almanack (1928)

Mostly following the indications of Natalie Barney’s and Janet Flanner’s annotated copies (the latter candidly admitting to not understanding much of the text), the almanac has been read as a roman à clef in which Dame Evangeline Musset is Natalie Clifford Barney, Patience Scalpel is Mina Loy, Lady Una Troubridge and Radclyffe Hall are Lady Buck-and-Balk and Tillie Tweed-in-Blood, respectively, Doll Furious is Dolly Wilde, Nip and Tuck are Janet Flanner and Solita Solano, Señorita Flyabout is Mimi Franchetti, Bounding Bess is Esther Murphy, and Cynic Sal is Romaine Brooks, just to name the main characters of this marginal cult work. Barnes herself, however, rejected such a reading; writing in 1976 of George Wickes’s Amazon of Letters to Berthe Cleyrergue (Barney’s long-standing housekeeper) and to Fabienne Benedict, she claims: ‘By the way, a Mr. Wicks [sic] writes me that he is writing something on the life of Miss Barney, saying he assumes that Ladies Almanack was based on her. I gave no authority for that opinion – including Miss Barney.’5 And again:

have you seen the ridiculous book on Natalie Barney, by one George Wicken [sic] (who is he?) and published by Putnam. Number of errors, of course. I was not to my knowledge ecer [sic] a ‘charity’ for the lady, nor was I called tha [sic] ‘red headed Bohemian’, nor did I ever give anyone authority to say that the Ladies Almanack was based on Miss Barney – including Miss Barney. The poor wretch Mr Wickes [name added in pen] means well, I dare say – that’s only a sample of the indignities of being published.6

If we interpret Ladies Almanack as depending on ‘hosts of private allusions [that] may never be unlocked’ we will have to agree with Terry Castle’s verdict of unreadability, and humorously consign it to oblivion, together with the purple writing of Liane de Pougy’s Idylle saphique (1901) or the ungracefully aged verses of Natalie Clifford Barney’s Quelques portraits – sonnets de femmes (1900).7

However, neither nostalgically lamenting the loss of private allusions nor uninhibitedly distinguishing the aesthetically valuable from the politically relevant will take us very far with Barnes’s work in general and with Ladies Almanack in particular. Although brilliant in identifying the book’s selling points,8 Barney’s letter to Aldington is not a very helpful reading of the text because it echoes rather than explore the way in which Ladies Almanack plays with the notion of a secret knowledge, or, we could say after Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, of the closet.9 I would like instead to provide an analysis of how Ladies Almanack produces its own unreadability and of how its difficulties belong to its economy of pleasure, suggesting that the lack of a key to open the text is part of the text’s own mechanisms rather than a historical shortcoming on the part of the readership; the private publication of the volume is not simply – as usually claimed – a way of evading censorship, but is integral to the text’s aesthetics; and the pseudonym of ‘Lady of Fashion’ evokes and mocks the power of the secretive author who is part of a clique.

Susan Sniader Lanser describes Ladies Almanack as a ‘singular, irreverent, and often ambiguous book that delighted for decades the people it parodied’; although she reports that three New York Times critics refused to review the Harper and Row 1972 edition because they could not decipher it, ‘the new scholarship’, Sniader Lanser states in 1992, ‘provides contexts for “decoding” Ladies Almanack’; she suggests taking ‘Barnes’s advice to “honour the creature slowly”, savouring rather than belabouring such phrases as “she thaws nothing but Facts” [and] “Outrunners in the thickets of prehistoric probability.”’10 To honour the text here means not to read it, but to partake in a pleasure that can be tasted but not understood. And yet, this text constantly reflects on the relation between pleasure and meaning, through its pen and ink illustrations that look like woodcuts, the presence of musical scores, and the linguistic excess produced by lists, exclamation marks, and baroque adjectivation. I would like to trouble the suggestion that in order to be as ‘delighted’ as its characters/readers belonging to the Paris clique allegedly were we have either to decode the text or read beyond or below it. Ironically, this refusal to read Barnes is yet another version of what Terry Castle has diagnosed as endemic to much scholarship on lesbian writers and artists: ‘when it comes to lesbians … many people have trouble seeing what’s in front of them.’11

Many are the critics who identify the pleasure of reading Barnes in unveiling, decoding, and unlocking. Mary Lynn Broe, for instance, speaks of her texts as forms of ‘encoding’ which she deciphers through biographical clues; Frances Doughty discusses the same problem as: ‘To tell, not to tell, to tell in disguise?’ and Anne B. Dalton claims that ‘Barnes’s work is more like Pandora’s box; once one manages to open it, the content streams out irrepressibly.’12 Yet, this operation is paradoxical to the extent that the critic who forces open Barnes’s work is faced by an eruption of titillating feminine horrors: ‘domestic violence, repressed lesbian desire, voyeurism, sexual exploitation, and maternal collusion.’13 We can see why an exasperated Barnes complained to her editor that people wanted her ‘upside down on 42nd Street, with my skirt over my head and my bum in the air.’14

Rather than decoding Ladies Almanack as if it were a riddle hiding a solution (which critics have often located in biography or context) I argue that the text’s difficulties are instrumental to opening up the relation between pleasure and meaning, that is to say to exploring the politics of representation. We cannot read Ladies Almanack just as ‘a prescriptive spoof for those who wonder what lesbians do (they muff-dive, sit on each other’s faces and ruin each other’s lives)’15 because while the text promises ‘glimpses of its novitiates, its rising “saints” and “priestesses”’ and plays with subcultures, puns, and double-entendres, it nevertheless resists displaying the lesbian as an object of wonder. The lesbian is never offered as a pure spectacle to be ‘savoured’ because it is not opposed to heterosexual normality: as can be observed in Barnes’s journalism, any form of representation is in the Barnes corpus inherently spectacular. Secrecy, misunderstandings, double-entendres, and wonder cannot be attributed to lesbianism from a straight point of view, as demonstrated by the mutually estranging narrative perspectives and by the dialogic interaction of Patience Scalpel and the other ‘Members of the Sect.’ To put it somewhat differently, the problem with Ladies Almanack is that one laughs, but one is not quite sure what one’s laughing about.

Ladies Almanack is a ‘marginal cult work’ because it promises access to the closed circle of the cult of Sappho while deferring right of entry and mocking the club. The hearth-shaped vaginal blazon on the title page parallels the text’s seductiveness (two sirens stand for the labia of this hearth-vagina), promising access to the busby-wearing Musset, peeping from its depth. The aorta/cervical canal is an arm brandishing – in a gesture between the military and the courtly – a flower, possibly a rose (Figure 1.2).

This picture is not just a decoration embellishing a text; it challenges instead the oppositional relation between beauty and truth (or aesthetic and conceptual dimensions): it calls for an interpretation but troubles any symbolic explanation. Refusing to illustrate the words, it parallels instead the oscillation between seduction and frustration that structures the text as a whole, questioning modernism’s ‘disciplinary purity’ and its ‘self-defining emphasis upon formal experimentation [, which] militated against genuinely cross-disciplinary work.’16 The pictures also generate supplementary meaning, since obscurities are not explained but amplified by these paradoxical ‘illustrations’, as demonstrated by the generic ‘antiquarianism’ of both textual and pictorial elements and by the presence of textual inscriptions in the images and visual elements in the text.

Fig. 1.2 Frontispiece, Ladies Almanack (1928), ca. 1928

The ingredients that make Ladies Almanack belong to the expatriates’ elite are the same that have turned it into a cult book, because most of its readers wish they had been in Paris (the right bit of Paris, that is) ‘back then.’17 This explains why for so many readers of this almanac the pleasure seems to be always lost, or located elsewhere; and yet, this is not because we modern readers have lost some mythical key to the text, but because in Barnes cliquey Bohemia (a central notion both to Ladies Almanack and to its reading history) needs to remain unreadable. This is illustrated by a 1916 article that Barnes wrote for the Sunday magazine of the New York Morning Telegraph entitled ‘Becoming Intimate with the Bohemians’, already briefly mentioned in the Introduction to this volume. Here, a ‘fur-trimmed woman’ (a ‘Madame Bronx’) and her two ‘certified daughters’ are engaged in a frantic search for the ‘true Bohemia’; the narrator of the article (which at times reads closer to a short story) emblematically refuses to ‘disclose’ many of the names of ‘those lost places that are twice as charming because of their reticence.’ She says ‘No, I shall not give them away, but I’ll locate them for those of you who care to nose it out as book lovers nose out old editions. … This is the real – this is the unknown.’18

Bohemia cannot be ‘given away’, in New York a...