![]()

Chapter 1

Performance

Performing P’ansori: Action and Event

A performance of p’ansori has to be understood in its social and cultural context. It is not limited simply to its theatrical presentation but begins with its organization and preparation, which may be long before the performance itself. The purpose of a performance, along with the settings, audience and the performer’s intention, shapes the actual performance outcome. Baumann’s definition of performance as carrier of a dual sense of artistic action and artistic event, explains the nature of p’ansori performance well (1977: 4).

In general, major performances of p’ansori presented in their full length, or wanch’ang (complete singing), are organized by sponsors, such as the National Theatre or the mass media, in a major concert hall. Wanch’ang presentation has been an important p’ansori performance format since Pak Tongjin (1916–2003) initiated this ‘tradition’ in the early 1970s. The publicity, which includes programmes, posters and advertisements, can be arranged by the organizer and/or the singer. The text of the piece to be performed is usually printed with an introduction by the sponsor with help from scholars who specialize in the genre. This text, called kamsangyong ch’angbon, is sold in the concert hall, so the audience can refer to it and follow the details of the story. Described here is a typical wanch’ang performance of p’ansori.1

The lobby of the concert hall is usually filled with flowers, which have been sent to the singer and also occasionally to the drummer by fans, friends, colleagues and students. The dressing rooms are often full of people who have come backstage to visit the performers. The performers generally warm up their voice or drum quietly before they go on stage. The singer, in particular, may have been on a special diet, which could include hanyak (oriental medicines), consisting of various herbs including ginseng, as well as nogyong (sliced deer antler) to enhance their physical endurance for the long and demanding performance.

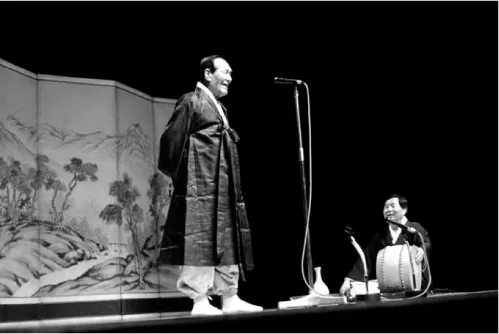

The stage set is simple: a folding blind, with landscape or calligraphy painted on it, stands at the back; a straw mat on the floor with a couple of cushions for the drummer and the drum. Sometimes, if the concert hall is too large for the natural sound to reach the back, microphones are set up on the stage or clipped to the singer’s costume. Otherwise, the singer may hold the microphone while performing or attach it to their upper garment, so that they won’t be restrained from moving freely especially when making dramatic gestures (pallim). A small table is also placed on the stage with a glass, a bottle of water and sometimes a bowl of salt for the performers. If the singer has a sore throat during the performance he or she can take a pinch of salt and some water to sooth it. However, it can be counterproductive if the singer takes too much.

As it gets close to the time for the performance to begin, the hall and lobby become filled with members of the audience, who usually know each other quite well. The majority of the audience will be middle aged or older, but there will also be quite a few younger people present, usually scholars and students specializing in Korean music or literature and university students who have become interested in the traditional performing arts. If the singer is from a city other than Seoul, the singer’s supporters may come as a group to listen to the performance of ‘their’ singer.

The sound of a bell tells the audience that it is time for them to enter the hall. Members of the audience may find some other familiar faces in the hall with whom they will begin to chat. In some venues there are no seat numbers on the tickets, and audience members then take seats wherever they are used to or prefer to sit. The first few rows of seats are often reserved for invited guests. People who arrive late may be asked to stay in the lobby until the intermission. However, there is often a monitor in the lobby where the performance can be seen and heard.

The performance begins after another bell. Since the 1980s, most p’ansori performances have a master of ceremonies, usually a senior scholar in p’ansori studies, who gives a speech and introduces the performers. The presence of academics provides extra credibility and respectability to the p’ansori artists. It also provides the sense of formality and authenticity expected from a proper p’ansori concert nowadays. After this, the performers enter the stage. The singer generally enters first, but sometimes – if he is older – the drummer does. The singer’s teacher may be introduced to the audience, and he or she may give a speech. In the 1980s, the master drummer Kim Tŭksu (1917–90) often also added an additional formal speech to bestow his ‘authority’ as one of most respected p’ansori artists of the time. He also often prompted responses from audience members by joking with some of the regular fans such as a gentleman known as Noryangjin Ajŏssi (Mr Noryangjin) from the Noryangjin District of Seoul. If Kim Tŭksu recognized this enthusiastic audience member, who always sat in the front row, he would say, ‘You are here again!’; Mr Noryangjin’s reply was equally humorous, ‘You cannot get away from me.’ In a similar manner, the audience could be more ‘tuned in’ to the whole atmosphere of the p’ansori performance event, as they make comments on the speeches and performers or exchange jokes in this way.

After these introductions the singer bows deeply and introduces him or herself to the audience, who are also thanked for coming to the performance in spite of the bad weather or their tight schedule and so on – this is a culturally prescribed discourse, which can be found in most formal functions in Korea, as well as in neighbouring Asian cultures. The singer will then mention their teacher, with a great deal of respect and modesty, saying: ‘My singing is so imperfect, when compared to my teacher’s, even to “imitate” them, yet, I shall try my best to meet their expectations.’ This particular speech serves several functions in a p’ansori performance. Firstly it can be understood as what Baumann described as ‘an appeal to tradition’ through which the singer declares their musical genealogy and pedigree. This is also ‘a disclaimer of performance’ serving ‘both as a moral gesture, to counterbalance the power of performance to focus the heightened attention on the performer and a key to the performance itself’ (Baumann 1977: 22).

Illustration 1.1 Chŏng Kwangsu singing an impromptu tanga piece at An Suksŏn’s wanch’ang performance of Sugungga, Small Hall, National Theatre of Korea, Seoul, 1987 (photo: Haekyung Um)

Then the singer and drummer are ready to begin. The singer stands in the middle of the straw mat. The drummer sits on the left-hand side of the singer on the cushion and tries the drum with a couple of rhythmic patterns. They may have an extra drumstick in case the first one breaks during the performance. The performers’ clothing is simple. Both wear traditional costume in plain or neutral colours. The singer holds a folding fan and handkerchief which are used as acting props.

The singer will usually begin by singing tanga (a short, introductory song) to warm up his or her voice before the p’ansori proper. Occasionally the singer’s teacher may sing tanga for them, if they are present. If the singer is capable of composing tanga on stage, they may dedicate it to the audience and event, as Chŏng Kwangsu (1909–2003) did for his student An Suksŏn’s wanch’ang performance of Sugungga (The Song of the Underwater Palace) in 1987 (see Illustration 1.1).

The p’ansori proper begins with aniri (narration or dialogue) and then moves to various sori (songs) which alternate with aniri. As the performance progresses the performer shifts from the narrator of the story to each character in turn, for example, Ch’unhyang, Yi Mongnyong, Ch’unhyang’s mother, or the new magistrate in Ch’unhyangga (The Song of Ch’unhyang). The singer can also simply be him or herself, as well as taking on the role of a member of the audience during the course of the performance. The singer unfolds the p’ansori story according to the particular stylistic tradition they subscribe to. However, this does not imply that two singers from the same school will render two identical versions since their strategies will tend to differ from one another (see Chapters 4 and 5).

As the storyteller, the singer narrates the story in the present tense to an imagined audience in the archaic style of the Chŏlla dialect. Simultaneously the singer also presents the story to the audience members who are present at the performance event who are addressed in contemporary Korean. For example, Ch’unhyangga in the style of Kim Sejong begins as follows:

Namwŏn Prefecture in Left Honam Province was, once upon a time, called Taebang Prefecture. In the first year of King Sukchong’s reign, there is a magistrate’s son. His age is sixteen, his face handsome, his demeanour upright, and his reputation widely known.

The singer occasionally switches perspective during the course of the performance, from the present tense of narrative to the present tense of the performance to take the performer’s point of view so that he or she can tell the audience what is about to be sung: for example, ‘“Chajin Sarangga” [The Love Song in Fast Tempo] that I am going to sing was composed by Ko Sugwan, a master singer from the past.’ The speech of the singer changes from the casual register of the archaic Chŏlla dialect to the formal register of modern Korean, mirroring the shifting perspectives of p’ansori narratives and the framing of the action.

The p’ansori singer also plays the third-party role of narrator, thereby connecting the songs and dialogues and describing or commenting on the dramatic situation. The singer will sometimes incorporate their own actions into the text in a live performance. For example, while performing the farewell scene from Ch’unhyangga, Sŏng Uhyang adapted the text as follows: ‘Ch’unhyang feels thirsty as she cries so much. So she drinks some water [the singer drinks], and then she cries again.’2 In this way, performances can be co-textual, alternating from one version of a text to a parallel situation in another text adding several layers of interaction. The key indicator of shifting perspectives in the communicative acts is the speech style and registers which are appropriately tuned to the parti...