![]()

1

A Case of Integrative Visual Agnosia (1987)

M. Jane Riddoch,1 and Glyn W. Humphreys1

Introduction

Visual agnosia is a severe modality-specific deficit in the recognition of visually presented objects. It is a recognition, rather than a naming deficit, since visual agnosic patients are unable to gesture the use or to show any recognition of the objects they fail to name. Typically, discussions of visual agnosia centre around Lissauer’s (1890) distinction between apperceptive and associative agnosia. Lissauer argued that visual object recognition was composed of two primary independent stages; apperception, the process of constructing a perceptual representation from vision; and association, the process of mapping a perceptual representation onto stored knowledge of the object’s functions and associations. Lissauer proposed that, following brain damage, patients may be impaired in either the apperception or the association process, with both impairments giving rise to a deficit in visual object recognition.

There have been several cases documented where visual object recognition deficits appear to be consequent on an impairment in establishing adequate perceptual representations of visual forms. For instance, the patient reported by Efron (1968) and Benson and Greenberg (1969) appeared to be impaired at almost any task requiring the discrimination of shape, despite having intact discrimination of size, intensity, distance and movement (see also Campion and Latto, 1985; Campion, 1987). Clearly such an impairment in using even simple shape information will render object recognition deficient. According to Lissauer’s definition, such patients appear impaired in the apperception process.

In contrast to the above types of patient, other patients with visual object recognition deficits may be relatively good at copying the objects they fail to recognize (e.g., Rubens and Benson, 1971; Ratcliff and Newcombe, 1982) and at matching photographs of objects taken from different viewpoints (e.g., Taylor and Warrington, 1971; Warrington, 1975). Indeed, Riddoch and Humphreys (1987) have recently documented the case of a patient who was poor at matching objects on the basis of their associative relations, and yet who was good at discriminating pictures of real objects from pictures of meaningless distractors which were closely matched for visual similarity relative to their real counterparts (an ‘object decision task’; see Experiment 3 below). With such closely matched distractors, object decisions may only be made with reference to stored knowledge about an object’s structure. Thus the latter case suggests that impaired visual access to functional and associative knowledge about objects may occur in the presence of intact access to stored structural knowledge. Clearly this case indicates that visual object recognition may be impaired in the presence of a normal perceptual representation of the visual world, consistent with a deficit in what Lissauer termed the association process.

The distinction between apperceptive and associative agnosia introduced by Lissauer emphasizes a two-stage view of visual object recognition. More recent accounts of the recognition process, while consistent with a two-stage view, also propose that both the apperception and the association stages may themselves be divided into various substages (e.g., Marr, 1982; Humphreys and Riddoch, 1987). The latter accounts predict that it is possible for each of these substages to be selectively impaired following brain damage and, therefore, for different types of ‘apperceptive’ or ‘associative’ impairment to result. Indeed, it may be that patients previously classed as either apperceptive or associative agnosics may illustrate damage only to some substages.

In the present paper we report a detailed case study of a patient, H.J.A., with a marked and selective deficit in visual object recognition. This recognition deficit seems to be of a higher order than that sustained by the apperceptive agnosic patients studied by Efron (1968), Benson and Greenberg (1969), Campion and Latto (1985) and Campion (1987). Yet we present evidence for its being consequent on a residual impairment in perceptual representation. We therefore suggest that the classification scheme for agnosia be expanded to incorporate such selective deficits in particular substages in visual perception.

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 1, we discuss H.J.A.’s performance on a series of diagnostic tests used to classify patients in terms of the apperceptive-associative agnosic dichotomy. The subsequent sections are then devoted to investigations of other aspects of H.J.A.’s recognition performance. Section 2 deals with H.J.A.’s recognition performance. Section 3 deals with his semantic knowledge and access to such knowledge from vision. Section 4 deals with his short and long-term visual memory. Section 5 deals with his ability to use context to facilitate object recognition. H.J.A.’s visual recognition impairment is attributed to a primary deficit in his perceptual representation of visual stimuli, and this deficit coexists along with intact semantic and visual memory, and an intact ability to make use of context. The implications of the case for accounts both of visual agnosia and the processes mediating normal object recognition are discussed.

Case history

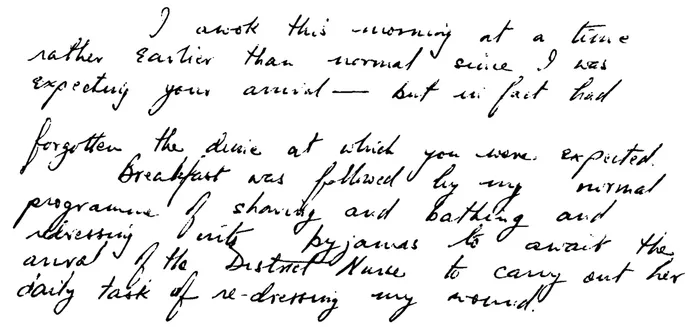

Details of H.J.A’s case history have been given elsewhere (Humphreys and Riddoch, 1984). Premorbidly, he was an executive who held responsibility for the European transactions of an American company. He suffered a stroke perioperatively in April, 1981, when aged 61 yrs. Subsequent to the stroke, his major problem was an inability to recognize common objects and faces by sight. He had acquired achromatopsia, showing a complete inability to discriminate colours. He also showed topographical agnosia, in that he was unable to recognize his environment by sight and he could easily become lost if moved away from a well-learned route. His reading was reduced to an accurate but slow letter-by-letter process. He had only a minor writing problem (see figure 1.1), but was typically unable to read what he had written (the reading of handwriting being a particularly difficult task for letter-by-letter readers; see Warrington and Shallice, 1980). H.J.A. had no memory deficits (digit span 8–9; see Sections 3 and 4 in the text for discussion of his semantic memory, his memory of the structural characteristics of objects, and his short-term visual memory).

FIGURE 1.1 Example of H.J.A.’s handwriting.

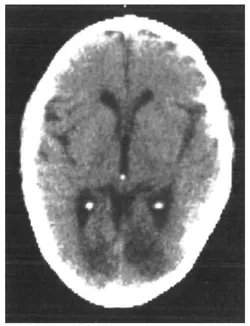

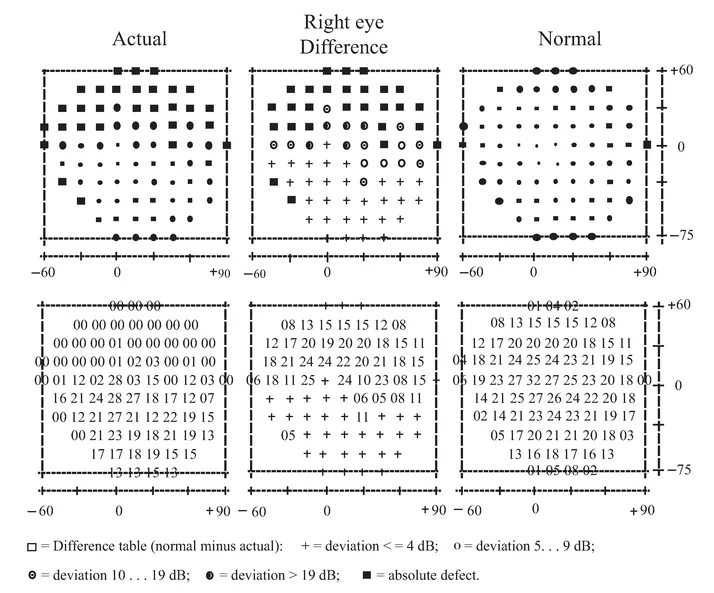

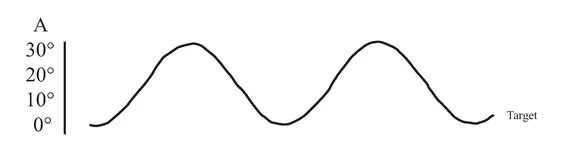

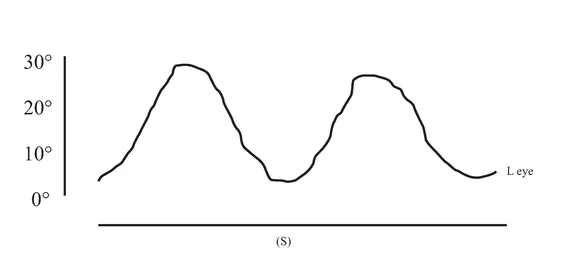

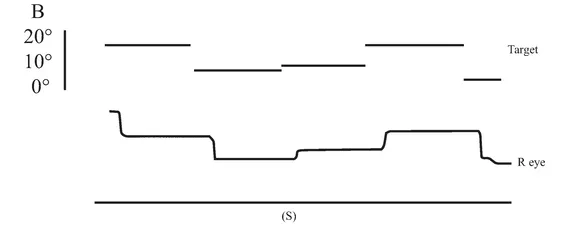

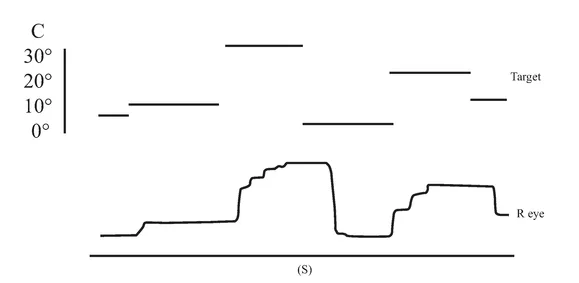

An initial CT scan ( May 1981) failed to reveal any marked neurological abnormalities, but a subsequent scan (June 1984) demonstrated extensive infarction extending forward in both occipital lobes in the distribution of the posterior cerebral arteries (see figure 1.2). Perimetric testing (using both the Goldman and the Octopus apparatus) showed a superior altitudinal defect of both the left and right visual fields (see figure 1.3). Responses from the lower fields were normal. Snellen acuity was normal. Visual evoked potential recordings showed normal patterns to stimuli presented to his lower visual fields, and no response to stimuli in his upper fields. Eye movements were recorded by both infrared and search coil techniques. Smooth pursuit movements (infrared recordings) were normal, as were horizontal saccades and downward vertical saccades to random targets at steps of 30 deg (search coil recordings). Vertical saccades upwards showed a staircase tracking pattern, consistent with his superior altitudinal field defect (see figure 1.4). No motor deficits were apparent, or expressive or receptive speech problems.

FIGURE 1.2 CT scan, June 1984, showing bilateral occipital infarction.

The present investigations were carried out in a number of sessions conducted between April 1981 and May 1985 during which time H.J.A.’s condition remained stable. The only slight improvement observed was in the visual recognition of very familiar household objects (knife, fork, spoon, cup, etc.). He was well orientated in time and place during all the test sessions.

Neuropsychological investigation

Section 1. Diagnostic tests

H.J.A. named 28/45 real common objects correctly from vision, but 36/42 of the same objects from tactile presentation. Tactile identification was reliably better than visual identification (χ2 = 5.02, P < 0.05). However, real objects were

FIGURE 1.3 Results of Octopus perimetric recordings of H.J.A.’s visual fields.

FIGURE 1.4 Examples of H.J.A.’s eye movement recordings. A, smooth pursuit movements; B, horizontal saccades; C, vertical saccades. Smooth pursuit movements of both the left and the right eyes were made. Only left eye movement is shown here.

easier to identify from visual presentation than photographs of the same objects taken from a prototypical viewing position (21/32 vs 12/32; McNemar test of change, χ2 = 4.90, P < 0.05). This shows that H.J.A.’s problem in identifying objects is modality specific, and sensitive to the visual information present in the stimulus. His identification is better given the extra information present in real objects.

When H.J.A. failed to identify objects correctly, he was unable to gesture their use. On simple function match tasks, involving the matching of line drawings or photographs of physically-different objects which can be used for the same function (see Warrington and Taylor, 1978), he performed poorly, scoring 12/20 with line drawings and 18/26 with photographs. His performance on the function-match task with photographs was worse than his ability to perform ‘physical’ match tasks. For instance, it was worse than his matching of photographs of foreshortened objects across different viewpoints (24/26; see Humphreys and Riddoch, 1984; Fisher Exact Probability P = 0.03). The function-match task is not more difficult than different-view matching task, as right hemisphere-damaged patients who are impaired at different-view matching can find the function-match test easier (e.g. D.B., reported in Humphreys and Riddoch, 1984, scored 23/36 on the function match test and 12/26 on the foreshortened-view test χ2 = 8.74, P < 0.01). H.J...