![]() Part I

Part I

Work in Progress![]()

Chapter 1

Before transition

In late September 1926, while Joyce was in Brussels, he wrote to Harriet Shaw Weaver that he wanted fragments of his ‘Work in Progress’‘to appear slowly and regularly in a prominent place’ (LI 245). Finding such a place proved to be harder than expected, though. Eventually, transition was to become this ‘prominent place’, but no matter how appropriate this magazine’s name may have been for a ‘Work in Progress’, the real years of transition were the ones between the publication of Ulysses in 1922 and the first instalment in transition, when Joyce did not find a place that could offer the slow regularity of publication he was looking for. At the same time, the restlessness of this period of transition also reflects the spirit of the age. In order to map the publication history of ‘Work in Progress’ it is useful to focus on the various magazines in which Joyce tried to get fragments of his new work published, taking Sylvia Beach’s advice: ‘The best way of following the literary movement in the twenties is through the little reviews, often short-lived, alas! But always interesting. Shakespeare and Company never published one. We had enough to do taking care of those published by our friends’(Beach 1980, 137).

On a sheet of paper, preserved in Buffalo, Sylvia Beach once made a list of the early publication history of ‘Work in Progress’, starting with the ‘First extracts in reviews’. The first section (‘Reviews’) does not mention transition, as it apparently represented a category of its own (see Chapter 3). It does mention The Calendar, though, but without number and with the parenthetic note ‘(not able to print a part of it ALP)’:

Work in Progress

First extracts in reviews

Reviews

- Transatlantic Review april 1924 Four Old Masters

- (anthology) Contact Collection June 1925 Earwicker

- The Criterion July 1925 The document

The Calendar (not able to print a part of it ALP)

- Le Navire d’Argent 1er Oct 1925 Anna LiviaPlurabelle

- This Quarter 1925–6 Autumn-Winter Shem the Penman (UB JJC XVIII.G, folder 20)

This sketchy list only represents what Sylvia Beach remembered of this early period of ‘Work in Progress’. T.S. Eliot was the first to solicit a fragment (McMillan 1975, 180), but Joyce failed to comply with this initial request for an instalment in The Criterion as he did not consider the fragments ready for publication (Crispi and Herbert 2003, 64). He did offer an instalment somewhat later, for The Criterion III, after having tried out several other magazines – transatlantic review, This Quarter and Le Navire d’Argent.

transatlantic review

‘From Work in Progress’, transatlantic review, Paris, 1.4 (April 1924), 215–23 [FW 383–398.30] (Slocum and Cahoon 1953, 100; C.62)1

After having established himself in Paris, in October 1923, former editor of the English Review Ford Madox Ford asked Joyce for a contribution to his new journal, the transatlantic review. Joyce explained his hesitation to Harriet Shaw Weaver on 2 November, as he thought the fragments he had already written were not quite ready to be published. The transatlantic review was not exactly the prominent place he was looking for. As Luca Crispi and Stacey Herbert note, ‘with its plain white covers and letters of welcome and praise by H.G. Wells and Joseph Conrad, the only thing that could be construed as avant-garde were the all lowercase letters of the title in the Paris and London editions, but even then the New York edition maintained the title in its more conventional typography’ (18). The first issues had contained ‘nothing aggressive, incisive, or even slightly eccentric’, according to Bernard Poli (Poli 1967, 56). Still, Joyce did prepare the ‘Mamalujo’ vignette (first drafted in September 1923; LI 205; FDV 213) for publication in Ford’s magazine (corresponding with Book II chapter 4 of Finnegans Wake, FW 383.01–398.28). In Finnegans Wake, this passage contains many elements of the ‘Tristan and Isolde’ sketch he had made in 1923, in which the love scene between Tristan and ‘the belle of Chapelizod’ is described as a soccer attack, Tristan (a ‘rugger and soccer champion’) driving ‘the advance messenger of love […] into the goal of her gullet’ (FDV 209), while the seaswans sing: ‘Three quarks for Muster Mark’ (FDV 212). This is one of five sketches centred around the kiss of Tristan and Isolde, which Daniel Ferrer beautifully dubbed ‘brouillons d’un baiser’ [‘drafts of a kiss’].2

As Jed Deppman has shown, Joyce ‘actively pulverized and recombined his textual elements, notably shattering “Tristan” and scattering its pieces into “Mamalujo”’ (Deppman 2007, 309). But this happened much later, in 1938. In the version of the transatlantic review, the ‘Tristan and Isolde’ sketch had not yet been merged. The piece in the transatlantic review, the first pre-book publication of ‘Work in Progress’, opens with the conjuntion ‘And’ and introduces Matthew, Mark, Luke and John or the Four Masters/annalists/historians: ‘And there they were too listening in as hard as they could to the solans and sycamores and the wild geese and gannets and the migratories and mistlethrushes and the auspices and all the birds of the sea, all four of them, all sighing and sobbing, and listening. They were the big four, the four master waves of Erin’ (TR 215)

The piece ends with the so-called ‘Anno Domini’ poem, introduced as follows: ‘Hear, O hear, Iseult la belle! Tristan, sad hero, hear! Anno Domini nostri sancti Jesu Christi’ (TR 223). The verses are personalized and composed according to a scheme, which was sent to Miss Weaver on 12 October 1923 (SL 296–7). In this scheme, each of the Evangelists is connected with one of the Four Masters (Peregrine O’Clery, Michael O’Clery, Farfassa O’Mulconry, Peregrine O’Duignan), with a pronoun (thou, she, you, I, respectively), with the four provinces of Ireland (Ulster, Munster, Leinster, Connacht), with their respective evangelist symbols, with a specific Irish accent and so on. Later on, Joyce also added references to Blake’s four Zoas on the separately revised pages of the transatlantic review (JJA 56: 125–33).3 The version in transatlantic review closes with the lines about ‘a wet good Friday’, followed by ‘an allnight eiderdown bed picnic’ and the lady, who gets the last word:

By the cross of Cong, says she, rising up Saturday in the twilight from under me, Mick whatever your name is you’re the most likable lad that’s come my ways yet from the barony of Bohermore.

(TR 223)

Dougald McMillan notes that ‘Ford’s transatlantic review had given him [Joyce] proofs so “grotesque” that he asked for a delay while the printer learned his trade’ (McMillan 1975, 179). Still, Ford had facilitated the first public appearance of a fragment ‘From Work in Progress’ and the title he suggested for the fragment in his review was adopted in subsequent publications. Thus, for instance, ‘Here Comes Everybody’ was introduced to the literary world as a fragment ‘From Work in Progress’ in the next instalment, published in the Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers (see Figure 1.1).

Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers

‘From Work in Progress’, in Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers (Paris: Contact Editions / Three Mountains Press, 1925): 133–6 [FW 30–4]

Contact Editions was run by Robert McAlmon, one of the typists of Ulysses and the author of A Hasty Bunch (1922). In the first issue of the transatlantic review, Robert McAlmon announced his plans to found the Contact Publishing Company: ‘At intervals of two weeks to six months, or six years, we will bring out books by various writers who seem not likely to be published by other publishers, for commercial or legistlative reasons’ (qtd in Beach 1980, 130). The announcement contained the following invitation to potential contributors: ‘Anybody interested may communicate with Contact Publishing Co., 12 rue de l’Odéon, Paris’. One of these authors who – at that moment at least – seemed not likely to be published elsewhere was the then relatively unknown Ernest Hemingway. Contact published his Three Stories and Ten Poems.

According to Neil Pearson, Hemingway referred to McAlmon as ‘McAlimony’, because he ‘used the money he had come into on marrying the heiress Winifred Ellerman (who wrote under the pseudonym Bryher) to bankroll a Paris imprint called Contact Editions. Without his wife’s money the small print runs and even smaller sales of Contact’s unbendingly highbrow list – combined with McAlmon’s innate lassitude and lack of business sense – would have seen the enterprise fail almost before it began’ (Pearson 2007, 3). McAlmon’s marriage not only enabled him to establish Contact Editions; as he was homosexual, Pearson suggests, it also enabled his wife to ‘break away from her family and pursue her relationship with the poet Hilda Doolittle’ (Pearson 2007, 6).

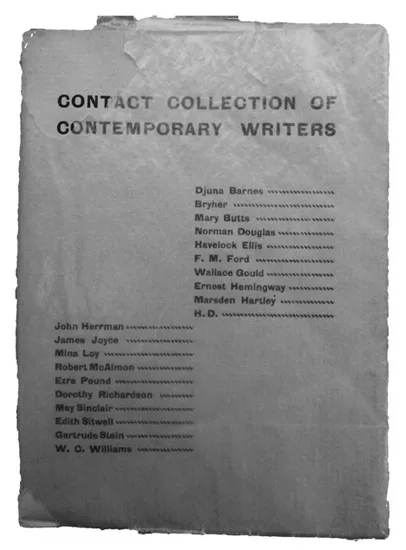

Figure 1.1 Cover of Contact Collections of Contemporary Writers

The contributors – including such authors as Djuna Barnes, Ford Madox Ford, Ernest Hemingway, H.D., John Herrmann, Mina Loy, Ezra Pound, Dorothy Richardson, May Sinclair, Edith Sitwell, Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams, in addition to Bryher and McAlmon themselves – dedicated the collection to Sylvia Beach, who mentions it in Shakespeare and Company, calling it ‘the most interesting book of scraps’ she had ever seen (131). These ‘scraps’ were fragments of whatever the contributors happened to be working on, which explains why Joyce’s contribution is not the only piece referred to as an extract ‘From Work in Progress’ (John Herrmann’s and Dorothy Richardson’s pieces had the same title). On 21 November 1924, Joyce wrote to Robert McAlmon, asking him: ‘By what date (latest) do you want my copy and on what date (earliest) will the book [Contact Collection] be out’ (LI 23). The collection would eventually come out in May 1925. In the same letter to McAlmon, Joyce mentioned he had to be operated on for cataract. It was not until after Christmas 1924 that his sight returned in his ‘occluded’ eye. In a missing notebook (VI.D.3, partially reconstructed on the basis of France Raphael’s transcription in notebook VI.C.4), Joyce made notes between December 1924 and February 1925 on Hester Travers Smith’s Psychic Messages from Oscar Wilde (London: T. Werner Laurie, 1923).4 In this book on spiritual messages sent by the ghost of Oscar Wilde to his mediums through automatic writing with the Ouija board, Joyce read what ‘Wilde’s spirit’ thought of Ulysses:

Yes, I have smeared my fingers with that vast work. It has given me one exquisite moment of amusement. I gathered that if I hoped to retain my reputation as an intelligent shade, open to new ideas, I must peruse this volume. It is a singular matter that a countryman of mine should have produced this great bulk of filth.

(Travers Smith 1925, 17; emphasis added)

Joyce used the words of the attack (‘this great bulk of filth’) for HCE’s defence in a draft of Haveth Childers Everywhere: ‘Who accuses me. My adversary, thehe is the first liar in hisof this land. Shucks! Suchbughouse filth as I cannotbarely conceiveof’ (British Library MS 47482b-113v; JJA 58:094). Wilde’s ghost felt that ‘even I, who am a shade, and I who have tasted the fullness of life and its meed of bitterness, should cry aloud: “Shame upon Joyce, shame on his work, shame on his lying soul”’ (Travers Smith 1925, 17). Joyce incorporated this criticism of his previous book (Ulysses) in his new work, notably in the fair copy of Haveth Childers Everywhere: ‘It is truly most amusin. There is not one teaspoonspill of evidence to my badbaad as you shall see as this is and I can take off my coats here before those in heaven to enter into my processprotestant caveat against the pupup publication of libel by any Ticks Tipsylon to that hightest personage at moments holding d...