![]()

Chapter 1

The City – From Market Place to Terminal

Cities as Markets: Trade and Transport as Origins of Urban Places

Cities and urban regions have always been significant nodes for the exchange of goods. Trade and merchandising, wholesale and retail distribution have been closely connected with urban places and urban development. Cities have been a central place by definition, for both city and region, and a gateway for providing goods and services to a more distant hinterland. Not coincidentally, the classical function of the city as a centre of goods transshipment has already been acknowledged in traditional urban theory. The sociologist Max Weber (1921, 61), for example, argued that the “regular exchange of goods” was one of the basic characteristics of cities, distinguishing a city from other, more or less ordinary settlements. One of the classical studies in urban and regional development, Walter Christaller’s Central Place Theory (Christaller 1933), had put particular emphasis on 1) the significance of the city for providing goods and services for the city and for the area beyond, 2) on the role of transport costs for defining its sphere of influence both from the perspective of the supply side as well as from the consumers point of view. The ability of the city to concentrate people and workforce, ideas and interactions, can be considered a constant factor in the process of urbanization. The spatial manifestation of this force of concentration was the significant role of the urban centre that lasted for centuries – until new means and technologies of mobility were changing the shape and the structure of the city. With respect to these changes, the theory of the multi-nuclear city developed by Chauncy D. Harris and Edward L. Ullman (Harris and Ullman 1945, 9–15) emphasized the foundation of the city as a generic transport focus, emerging from the demand for “break of bulk” and related services and amenities. This generic urban significance of the system of goods exchange was particularly fostered by interregional trade that made some cities becoming nodes within a large-scale network of commodity and money flows. Once analysing the emergence of the medieval trade economy, the French historian Fernand Braudel described urban places that were committed to organize trade and retail as “trading spaces” (Braudel 1982, 26 ff.), like market places or market halls, warehouses and finally trade fairs. Port cities performed and further developed such properties in a particular way. Some of these cities, like the port city of Hamburg in Germany, the old trade city of Antwerp in Belgium or the prototypical “gateway city” in Chicago in the U.S., have retained this property until now. Others developed in different directions and have specialized in manufacturing or services, more recently in high-technology, knowledge-intensive activities or leisure and tourism. Even in these cases, providing accessibility for the flows of goods and people (and also information), remains important for urban development in general.

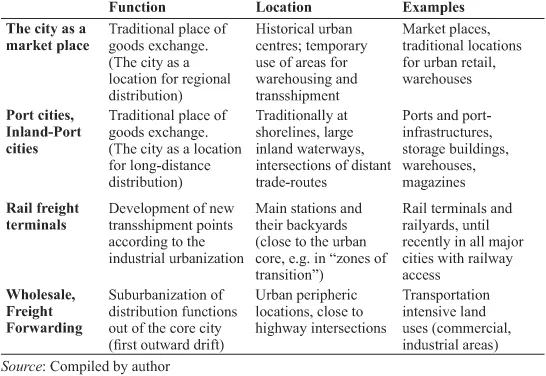

Theories on urban structure and urban land use had also shed some light on the importance of trade and the related movements. Burgess’ classical study on the concentric model of the city of the twentienth century included the emergence of specific districts for hosting the provision of commodities, such as wholesaling or light manufacturing in the zone of transition, which was traditionally located close to the city centre. Since manufacturing was once concentrated in the urban core, a major reason for the location of industry and derived from that of distribution was explained by the advantages of urban agglomeration in terms of transportation and labour orientation, according to Alfred Weber’s theory of the location of industries (Weber 1929, 41 ff., 95 ff). As a consequence, the provision of goods was important for the development of particular urban places confined to storage, goods handling and processing. Such places were found both on-site of the industrial plant and adjacent, also in dedicated commercial areas or in more remote facilities, respectively (see Table 1.1). The remainders of this period are so-called wholesale districts with warehouses and loft-buildings, also urban waterfront areas with past and present transshipment functions, or secondary industrial warehouses. Due to changes in urban land use, and in response to new logistical requirements, these places have been the subject of urban regeneration projects and are normally no longer associated with organizing material flows (Hesse 1999).

Table 1.1 The traditional place of goods handling in urban areas

The Industrial Revolution and the accelerated urbanization that occurred during the last third of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentienth century have underpinned these developments. Industrial urbanization can not only be understood as a special mode of creation of value through materials transformation, but it became strongly connected with the development of mass transport technologies in general and the railway system in particular. The emerging “sphere of circulation” was of course extremely important for the shape and the structure of the industrial city. Once rail freight and passenger transport became predominant modes of distribution for decades, a new network infrastructure had been exposed to urban and suburban areas providing for accessibility in a new format, also subdividing and fragmenting urban space due to the specific layout of the roadbed. Beyond the mere establishment of rail tracks and stations, transshipment terminals and extensive railyards were established that covered a significant amount of space in urban core and fringe areas. Altogether with large manufacturing plants, this setting would later be considered a typical image of the “Fordist” city. Again, the making of the gateway city of Chicago (Cronon 1991) had been strongly associated with a new centrality and an expanded spatial reach offered by the railway system.

The coming of the motor truck has altered this picture again. This happened in the U.S. during the first half of the twentienth century, in most industrialized countries such as in Europe after World War II. The direct door-to-door services offered by the motor truck allowed for a completely new flexibility in terms of space and time – a seemingly appropriate response to the increasingly dispersed urban landscape and fragmented spatial economy. In one of the rare contributions that covered the influence of goods movements on urban and suburban areas, notably that of trucks, Jackson (1992, 1994) pointed out as follows:

Truck transportation in the 1920s had proven already that it was fast, flexible and cheap, so one important reason for wanting a new layout for factories and warehouses was the provision of efficient loading and unloading facilities for the truck – facilities that integrated the doors and tailgate of the truck into the horizontal interior of the plant. […] Accordingly, factories and warehouses began deserting the crowded town area and moving out to where land was cheaper and closer to the highways used by larger trucks. So the truck – or the increased use of the truck – contributed to the decay of the inner city and the growth of industries in the outlying districts. (Jackson 1992, 21)

So the motor truck forced the drift of economic activity away from the fixed topography determined by the location of cities and the layout of railway lines (as the refrigerator wagon had triggered the massive expansion of economic catchment areas earlier). These logistical innovations reinforced the growth of freight transport, and they stimulated urban and regional development in general. The main comparative advantage of the motor truck compared to rail and waterway transport was to combine spatial reach with temporal flexibility; moreover, the truck made the change of vessels that had happened before in ports or railyards mostly obsolete, thus reducing delivery times and costs along the supply chain. As long as the volume of commodity shipments did not exceed certain limits, and the size and the weight of freight cars were in line with street design and grid patterns, freight transport still worked as a “maker” rather than a “breaker” of cities, speaking in the terms of Colin Clark (Clark 1959).

This property of the logistics systems has been changing first once freight distribution followed commercial and industrial corporations in their historical move toward suburban locations. The more developed the urban fringe was becoming, the higher was the need for services in order to organize the goods and materials supply for businesses and households.

At the turn of the century [the truck] had been a humble, little regarded conveyor of heavy loads, slowly and noisily lumbering between station and warehouse. Twentyfive years later, it had not only acquired its own unique form and status, but it had acquired the power to alter the built environment, helping to determine the location, plan, and effectiveness of many commercial buildings. (Jackson 1992, 21)

This particular contribution of freight distribution and logistics to developing, and later urbanizing, certain parts of the urban area, particularly suburbia, had been overlooked in the past, once urban studies mainly emphasized the role of the passenger car in pushing settlements beyond city limits. However, Rae who coined the new logistics hubs that replaced the warehouse a “transit shed”, had simply stated: “Motor carriage not only encouraged suburbanization but also influenced the form that it took” (Rae 1971, 251). With the rising enrichment and emancipation of the periphery from the old centre, suburbia took over the function of the interface between city, region and places beyond, thus becoming a major hub in terms of logistics and freight distribution.

Suburbanization, Industrial Development and the Rise of the Poly-centric Region

Recent Patterns of Suburbanization in Germany

Consequently, any exploration of the relationship between logistics and urban development has to reflect that recent urbanization was predominantly shaped by tendencies of spatial de-concentration – which applies for the majority of the highly industrialized countries and lasted for decades. This was also the case in the Federal Republic of Germany for the period following World War II, as it was in North America, where suburbanization began some decades earlier. The de-concentration process affected the large agglomerations where out-migration of population and employment created extended suburban zones around the central cities (BBR 2005a, 191ff.). Also, an increasing de-concentration of economic activities took place, partly as reaction to population suburbanization (in the case of household oriented services), and partly caused by the intrinsic locational dynamics of certain economic activities like for instance manufacturing. Also space consuming activities like wholesale trade and logistics exhibited already in the 1970s a preference for suburban locations with good accessibility (Hesse 1999). High level producer services on the other hand remained more strongly attached to the city centres with certain exceptions like the Rhine-Main Region and Stuttgart (Eisenreich 2001).

Since the 1980s the growth dynamics in the large agglomerations have been shifting gradually from the old cores to the urban fringes and the rural surroundings (Hesse and Schmitz 1998; Schönert 2003). Medium-sized cities beyond the metropolitan areas began to form their own suburban rings. Central cities and surrounding areas merged into functional urban regions that form the spatial basis of daily activity systems for a majority of the population. This process varied in different metropolitan areas, depending on the specific historical and spatial settings: mono-centric metropolitan areas such as Hamburg or Munich showed spatial patterns different from poly-centric regions like the Ruhr, Rhine-Main, Rhine-Neckar or Stuttgart, where typical suburban locations had been traditionally mixed with older centres. The Berlin metropolitan area, where the division of Germany had formed two separate territories, presented a special case: for different political reasons, suburbanization processes predominantly took place within the city boundaries until reunification in 1989/90, particularly in the western part of Berlin.

The process of unification in Germany in 1990 represented a step forward to suburbanization dynamics in Germany (Siedentop et al. 2003; IÖR et al. 2005). It led to an accelerated suburbanization especially in East Germany that had persisted until the end of the 1990s. A major rationale for this acceleration was a lack of regional planning guidance to limit the land offers of suburban communities and also fiscal incentives for new housing construction as well as restrictions on inner city construction, due to unsettled claims for property restitution. These factors steered a large portion of the demand for housing and retail facilities to the outskirts. Since the end of the 1990s, suburbanization dynamics have been declining significantly and came to an almost complete stop in East Germany, except in the Berlin metropolitan area. Some East German urban regions even reported a reversal of the migration direction in favour of the central cities (Herfert 2002, 338). This reversal is likely to be more than just a brief cyclical interruption of a continuous de-concentration tendency. In West Germany the de-concentration process continues, but its focus has shifted from the outer suburban areas to the urban fringes, that is to say, closer to the central city (Siedentop et al. 2003). Counterurbanization tendencies that were still noticeable in the 1990s had stopped, and the overall intensity of suburbanization diminished. Since 2000, the large West German cities have again a positive population development.

With the expansion of the settlement and commuting areas, the system of the settlement structures and the central place hierarchy had changed as well. The growth of the commuting areas often followed the ideal-typical curve of land prices (Motzkus 2002). A more or less economically rational behaviour of actors, who were attracted by low prices for rents and real estate, is generally regarded as a central impetus for suburbanization. Regarding the supply side, growth strategies of the suburban communities with extensive supplies of land for development that made regional planning controls inefficient have to be mentioned (Aring 1999). While accessibility was an important factor for suburbanization, the negative effects of high traffic volumes are regarded as one of the most pressing problems of suburban areas today. It was also criticized that the once sharp phenomenological distinction between the spatial categories of “town” and “country” is increasingly blurred. The adjustment of living conditions and concomitantly of the spatial settlement structures is, however, an almost inevitable consequence of modernization: the more suburbia appears “mature”, i.e. the higher may the settlement densities of suburban locations become, the more heterogeneous their social structures are. Therefore the supplementation of residential uses by other functions is more likely. In this context suburban areas begin to resemble original properties of the city.

Summing up the tendencies outlined above it can be stated that suburban areas experienced a substantial – if regionally differentiated – revaluation over the last decades. They did not separate functionally from the central cities but have become integral parts of newly formed larger urban regions. The different parts of such urban regions are increasingly differentiated and selectively used in the course of what might be called a “regionalization of daily life”: Housing takes place in the countryside or in the city, depending on income and certain phases in the life cycle. Labour is situated either in suburbia or in the inner city and spending one’s leisure time is going on both in suburban areas or in the metropolitan cultural centres (Priebs 2004). Thus the spatial fix-point of the organization of everyday life is no longer the city centre, but are the individually shaped networks of activities which may stretch over the entire urban region and beyond. Urban research and regional planning reacted upon these changes by designating new concepts and new spatial categories. The “Raumordnungsbericht 2005” (Federal Report on Spatial Planning and Development) introduced the new spatial category “Zwischenraum” (intermediate space), which is positioned between the “Zentralraum” (central space) and the “Peripherraum” (peripheral space), which is characterized by specific properties concerning centrality, population potential and accessibility (BBR 2005a; BBR 2005b). Spatial categories that cover the suburban areas are “outer central space” and “intermediate space with agglomeration tendencies”. Using these spatial categories, 33.9 per cent of the population and 31.4 per cent of the total employment can be considered suburban in 2003 (ibid.). A different approach by Siedentop et al. (2003) defined a radius of 60 kilometres around the centre of an agglomeration as being suburban. Subtracting the central cities from the total area inside this circle, it was estimated that about two thirds of the population lived in the suburbs and about half of the employment was located there (ibid.).

Sub- and Ex-urbanization in North America

The United States and Canada are often considered the prototypical cases of suburban development. Without neglecting the roots of modern suburban housing in the Victorian England (Fishman 1987), the model of spacious living in a single-family home became famous primarily after being adopted by a large portion of the middle-class in the U.S. (Teaford 1986). In comparative perspective, and given that there are basic commonalities as well, suburbanization in Europe and North America is characterized by divergence in terms of the extent and size of suburban dwellings, density and mixed use of urban design, and average distances e.g. in terms of daily travel. Being important determinants, the planning system and the socio-economic framework and cultural attitudes appear quite different.

The core process of suburbanization in North America was constituted by three different, interrelated developments: 1) the dispersed urbanization of the periphery in a certain distance to the core city; 2) the decline of the old downtowns, from which many of the now suburbanites had flown; 3) the emergence of new centres in the periphery often labelled as “edge cities”. According to the classical studies by Douglass (1927), Binford (1985), Jackson (1985) or Fishman (1987), North American suburbanization already took off in the mid nineteenth century. Even if significant parts of suburbanization started as the selective movement of households from the core cities into the suburbs, the shift of retail and industry was much more than consecutive. As the study of the history of urbanization has put forward recently, there has always been an independent and immediate occupation of suburban space as well. The two processes of outward movement on one hand and direct suburban locational choice on the other hand were periodically connected. This was particularly true for the development of classical suburban settlements and industrial suburbs (Taylor 1915).

More recently, jobs that have either been moved to, or newly created in, suburbia, appear more advanced than before and are no longer confined to space extensive-routines in “back offices” or even mere warehouses. Retail and office functions and modern high-tech manufacturing have also occupied suburban space. As already mentioned, new centres emerged at the intersections of major highways on the edge of urbanized areas without almost any connection to the core city, yet, with a tendency towards a more self-reliant urbanization. Such new urban nodes have extensively decoupled from the old core cities, looking like something completely new rather than being just an extension of a suburb. They are found almost around all major metropolises of the U.S.; Garreau (1991) once identified 17 in the greater New York area, 16 in the Washington D.C. area. The Santa Clara County in the south of San Francisco or Orange County in Southern California represent poly-nuclear forms of “edge cities”. Meanwhile almost 90 per cent of all U.S.-retail sales are being made in suburban areas and out-of-town-or edge-city-centres. These centres host two thirds of the entire North American office occupation, with about 80 per cent being provided in the last 20 years. The emergence of edge-cities has transformed the image of suburban areas significantly, even if the thesis behind was quite controversially discussed.

Edge-cities and suburban agglomerations are mingling together building a poly-centric urban landscape, perhaps among the most dynamic parts of recent North American urban development. This “post-industrial Metropolis” consists of housing areas, schools and hospitals, malls and shopping-strips, office parks, industrial parks and theme parks, in a more or less loose association. The spatial scale of these semi-urban regions is no longer the “… block-wise street pattern, but the growth corridor stretching along 50 or 100 miles” (Sudjic 1993). Lang (2003) has recently coined this type of settlement the „edgeless city”. The target point of immigration into these places is no longer the core city, but the entire topographic space.

According to the latest U.S. Census, the 90s-decade saw a population increase by 13.2 per cent up to 281.4 million people and was the only one during the twentieth century that witnessed population gains in all U.S. States (U.S. Census Bureau 2001; Katz and Lang 2003). Whereas big cities such as New York or Chic...