![]()

1 John Wesley’s mission

Steering a course between sound and spurious enthusiasm

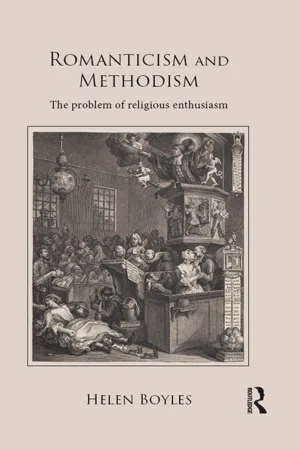

In 1762 William Hogarth produced a caricature of enthusiastic devotion in a Methodist meeting house. Entitled Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism, the print depicts a histrionic preacher addressing listeners in various stages of ecstatic abandonment.1 The implied culprits are the authors of the literature shown lying about the meeting house: the writings of George Whitefield and John Wesley, evangelists of revivalism. The lecherous expressions and amorous fondlings of couples in the foreground also dramatise the way in which Methodism was seen to inflame carnal desire through delusions of divine favour in the rhapsodic throes of the ‘New Birth’ conversion experience. Methodism-induced enthusiasm supposedly provoked hysteria and extravagant and superstitious claims. The image of the woman in the front left of Hogarth’s print giving birth to rabbits draws on a notorious case of deception in 1726 and satirises these hysterical and credulous tendencies while ridiculing the bodily metaphor of the new birth.2

Irreverent, exaggerated representations of eighteenth-century Methodism were provoked by an affective theology disseminated through the popular pulpit, printed testimony, and the journals of its leaders. Hogarth’s caricature was verbally replicated in the literary satire which Methodist enthusiasm also inspired. One example parodies the rhetorical inflation of the Methodist preaching style in language that expresses manic delusion and presumption:

O thou celestial source of ecstasies,

Of visions, Raptures, and converting Dreams.

Awful Ebriety of New-Birth Grace!

Thou, MANIA, I invoke my pen to guide,

To fire my soul, and urge my bold career.3

John Downes, Rector of St. Michael, Ward Street, believed that Methodists could be identified purely by their theatrical pulpit style. He urged vigilance against preachers displaying such characteristics as pretenders who must be barred from the respectable pulpit.

Sometimes a preacher unhappily incurs it by his Voice, Manner, Gestures, Pronunciation, nay, even by his very Countenance – Sometimes by the Pathos of his Stile, and the Vehemency of his address. … But then sometimes again, he brings it upon himself; as by heaping Scripture upon Scripture, either foreign to his Subject, or unconnected with his Matter; by a studied and more frequent Repetition, or hackneyed use of the adorable name of Jesus, than is either prudent or decent; by being fond of rapturous expressions, and high Flights of Piety, soaring quite beyond the Regions of reason and Common Sense.4

An enthusiastic style was felt to lack the proportion, restraint and rational focus which observed the tenets of polite taste.

Eighteenth-century Anglican vicar Richard Graves found material and language for fictional satire in the journals of Methodists. In his affectionate parody of Methodism, The Spiritual Quixote, he adapted a 1740 journal entry by John Wesley and combined it with material from a 1739 entry from the Journals of George Whitefield.5 Like Wesley in the original source, the novel’s itinerant Methodist hero, Mr. Geoffrey Wildgoose, stirs the emotions of his listeners at a Methodist Society meeting. As in Wesley’s entry, Wildgoose’s sleep is later disturbed by:

A number of people [who] had worked themselves up to such a pitch of religious frenzy that they some were fallen prostrate on the floor, screaming and roaring and beating their breasts, in agonies of remorse for their former wicked lives; others were singing hymns, leaping and exulting in ecstasies of joy that their sins were forgiven them.6

The emotional and physical excitement provoked by the ecstatic experience of the New Birth – the knowledge of Christ’s saving grace – was reflected in the heightened language and dramatic metaphors employed by adherents throughout the history of revivalism. This, for Wesley, was the Extraordinary Call of divine inspiration, as distinct from the ‘Ordinary’ call of clerical vocation and purpose.7 A letter in the Methodist Arminian Magazine related how the ‘power of god in a wonderful manner filled the room and the cries of the distressed instantly broke out like a clap of thunder’.8 John Wesley employed a similar rhetoric when he described how, at a disrupted meeting in the Foundery Chapel in London, suddenly, ‘the hammer of the Word brake the rocks (of evil) in pieces’.9 His journal also reproduced a letter which related how, in Limerick, those assured of God’s grace ‘trembled, cried, prayed and roared aloud, all of them lying on the ground’.10 The hyperbolic style of much popular testimony was ridiculed for histrionic excess, and generally ascribed to ignorance and credulity.

Equally prevalent was the language of sentiment, gendered as feminine. This discourse also characterised the secular literary culture of sensibility where a fictional heroine might be seen ‘melting with pity for every human woe’.11 This style is echoed in the language of Whitefield’s journal when he describes how he preached on one occasion to ‘about twelve thousand’ listeners:

I had not spoken long before I perceived numbers melting. As I proceeded, the influence increased till at last (both in the morning and the afternoon) thousands cried out, so that they almost drowned my voice. Never did I see a more glorious sight. Oh what tears were shed and poured out after the Lord Jesus. Some fainted; and when they had got a little strength they would hear and faint again.12

An account of the death of Methodist Jasper Robinson describes the dying man’s room ‘filled with the glory of God, and their (mourners’) hearts were as melting wax, while bowed before him’.13 This language of ‘the heart’, a dominant metaphor in evangelical testimony, encouraged the amatory analogies of Hogarth’s salacious portrait and other criticisms of the movement’s ‘feminine’ sensuality. For sophisticated observers, and especially those, like the Rev. Graves, anxious to defend establishment practice, the emotional excesses of the Methodist meeting were dryly viewed as ‘a species of folly which has frequently disturbed the tranquillity of this nation’.14

John Wesley’s revivalist mission was dogged by this popular perception of Methodism as synonymous with a manic enthusiasm that offended both sense and decency. As I explore in this chapter, much of his time was devoted to defending his movement from such aspersions. Ronald Knox described John Wesley, perhaps too easily, as ‘determined not to be an enthusiast’, and Hempton refers to ‘Wesley’s tightrope marches across the ravines of religious enthusiasm’.15 ‘Ravines’ nicely expresses the threat posed by any association with enthusiastic excess, though ‘marches’ conveys a confident assurance which belies the complex ambivalence of Wesley’s own relationship with enthusiasm. Certainly the image of a tightrope communicates the tense and precarious balancing act which John Wesley’s defence of ‘heart religion’ involved. Wesley attempted to dignify the image of Methodism by distinguishing its passionate but rationally founded faith from a spurious and self-serving zeal. This was a preoccupation reflected in over two hundred references to ‘enthusiasm’ in his writings.16 I open my analysis of Wesley’s complex relationship with enthusiasm by supplying a brief biographical outline of his foundation and early development of the Methodist movement within the broader historical context of contemporary religious culture.

The origins of John Wesley’s Methodism

Born in June 1703, John Wesley was the fruit of his parents’ reunion after a tense period of separation owing to differing political loyalties. His distinctive character could thus be seen as having been forged through a reconciliation of opposites.17 Wesley came to maturity in an age that exhibited similar contradictions and in which legislative efforts and debate were motivated by a desire for both political and religious stability.18 Since the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 and through the later accession of the Protestant William and Mary in 1688, there had been official toleration of Dissent, though by the eighteenth century persistent restrictions on Dissenters’ educational and professional opportunities discouraged many from joining the ranks of the Dissenting sects. However, the rational and liberal challenge to the established Church gained momentum from the early part of the century with Calvinist-inspired Presbyterianism critically engaging with doctrines of predestination and the Trinity. In 1774 this would find formal expression in Unitarianism, the creed that was to attract the liberal thinkers of late eighteenth-century literary Romanticism.

John Wesley – and later, William Wordsworth – were influenced by the teaching of William Law who, in his Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728), advocated ‘reasonableness’ and ‘duty’ against extremism or didacticism in religious observance.19 At the same time, Wesley was receptive to the spirit of High Church or Puritan piety which infused Law’s teachings. This spirit was disseminated in prominent Dissenting denominations such as the Presbyterians which persisted into the 1730s and were to become fruitful sources of support for the evangelical revival. From the first half of the eighteenth century, the earlier austerities of Dissent were also animated by the emotional inspiration of the hymns of Presbyterian divines Isaac Watts and Philip Doddridge who attempted to renew the passion and mystery of religion and through their personal and reflective hymns helped to establish a climate receptive to revivalism.

Although eighteenth-century Methodism gained strength from a perceived deficiency both in the established church and its Dissenting offshoots, it arose, as Henry Rack convincingly argues, from a persistent devotional tradition in English religious culture.20 From the 1730s, this residual Puritan piety found expression in the evangelical initiative which sought to revive an earlier apostolic Christianity. With its emphasis on revealed, supernatural, scriptural religion, Methodist revivalism was in marked contrast to the rationalist bias of contemporary religion and the secular spirit of good sense which characterised mainstream Anglicanism.21 The moralistic focus of contemporary religion was also challenged by the revival’s central emphasis on the traditional Reformation doctrine of justification by grace through faith as the only foundation for good works. To some extent Wesley’s personal, inward religion drew on a supernatural belief system which amongst the less-educated classes persisted into the age of Enlightenment. The rational Wesley nevertheless remained receptive to supernatural interpretations of physical seizures and visions claimed by disciples as divine revelation. Although extravagant physical manifestations of the New Birth were foreign to Wesley’s own equable temperament, he remained fascinated by what they seemed to suggest of the mysterious operations of the spirit, and took them seriously enough to record them in his journal. Throughout his life he would ascribe to providential intervention such events as natural accident, physical recovery from illness or preservation from danger.22

Methodism’s simpler evangelical genesis presented a contrast to the critical literacy of Rational Dissenting sects such as Unitarianism. Erik Routley attests that rationalist Dissenting sects like the Quakers and Unitarians ‘had little to do with the evangelical revival’, although the Unitarians from the last quarter of the eighteenth century were careful to distinguish their intellectual authority from the ‘philanthropic aristocracy’ of the Quakers.23 However, Wesley’s Methodi...