![]()

1

Sarah Records (1987–95) and the Everyday

‘Sarah’ is the name of a record label. (Haynes and Wadd 1995)

everything is given, without provoking the desire for or even the possibility of a rhetorical expansion. … we might (we must) speak of an intense immobility, linked to a detail (to a detonation), an explosion makes a little star on the pane of the text or of the photographer: neither the Haiku nor the Photograph makes us ‘dream’. (Barthes 1981: 49)

Originally the haikai must have been a game of chain-rhymes begun by one player and continued by the next. (Huizinga 1980 [1949]: 124)

Introduction

AIMS AND CHAPTER OUTLINE

In 1987, Matt Haynes co-founded with Clare Wadd the record label Sarah Records (1987–95). The Bristol-based non-profit independent record label was run from the domestic, everyday setting of a Bristol ‘tiny basement apartment’ (Alborn 1988). The record label spawned from Matt Haynes’ previous engagement with self-publication (as editor of the fanzine Are You Scared To Get Happy?, 1985–87) and self-released and self-distributed, home-recorded music. The aim of the chapter is to examine the relationship between Sarah Records and the everyday, as it is momentarily petrified and ‘lived in the medium of cultural form’ (Osborne 1995: 197). The study of the everyday and its transient materiality will encompass several scales and aspects with an emphasis on urban environment and geography (which unarguably provides the first, most immediate incarnation of material culture). First of all, Sarah Records will be envisioned as a fluid and transient practice through the operative metaphor of the Saropoly game: the record label will be regarded as a practice of playing, that is to say of inhabiting (through diversions) a given space and time (Bristol in the late 1980s–early 1990s). I will open a discursive space between popular music theorists such as Hesmondhalgh, Reynolds, and Borthwick and Moy and thinkers of the everyday such as De Certeau and Lefebvre, notably by linking the do-it-yourself (DIY) ethos to De Certeau’s notion of making do and sabotage. This initial macro-analysis of Sarah Records as a mundane practice of playing will be complemented by a closer focus on the artefacts released by the label. The way Sarah Records both literally and figuratively mapped the territory of the everyday will be a central concern of the chapter. Thus I will especially examine the status of Bristol within the economy of the record label to show how an alternative cartography of the city was designed through specific artefacts and gestures of appropriation (in techniques as diverse as photographing, writing and borrowing pre-existing names and symbols). Finally, I will offer an emphasis on the archival aspects of Sarah Records and propose that the record label fashioned a coherent spatiotemporal site, likely to be revisited and, as it were, available for future excavation. The material culture of the record label will be considered as that which helped in (paradoxically) creating, sustaining and disseminating a more immaterial narrative or myth of Sarah Records.

Throughout the chapter, objects will be thereby envisioned as part of a broader system of circulation and transmission, both in the physical world and in the world of language. The entwinement of practice and objects, which may ultimately lead to their effacing (for example, when objects become the prompts for the intangible telling of a story), is what makes them especially difficult to grasp and define. One way of avoiding such an aporia is to consider the material and immaterial as co-producers of meaning. If, on the one hand, the thing may effectively be a reification of action, on the other hand, the thing is also what triggers further ideas or actions. As correctly pointed out by Attfield in her study of the material culture of everyday life:

it is not the ‘thing’ in itself which is of prime interest … even though it is positioned as the central point of focus. The material object is posited as the vehicle through which to explore the object/subject relationship, a condition that hovers between the physical presence and the visual image, between the reality of the inherent properties of materials and the myth of fantasy, and between empirical materiality and theoretical representation. (Attfield 2000: 11)

TRACES OF SARAH RECORDS

During the existence of the Sarah label, the two founders duly produced, as they had planned, ‘100 perfect releases’ (Haynes and Wadd 1995) thus realizing a tangible, self-referential story of the label. It is this material story, realized not just in music objects as diverse as vinyl records, flexi-discs and fanzines but also a board game (the Saropoly), that I wish to examine in this chapter. Objects, as well as the lived, material space of the city which informed them, were central to the aesthetics and politics of Sarah Records. As such, the artefacts released by the label may be perceived as miniature representations or fragments of the city, offering memory prompts notably in the form of photographs incorporated into the artworks and fanzines or autobiographical texts, as if to echo Benjamin’s dream of ‘setting out the sphere of life – bios – graphically on a map’ (Benjamin 2000 [1979]: 303). Through the objects they created the two founders of the label sought to promote and record their own, lived version of Bristol. It may be argued that Sarah Records existed as a multiple venture with literary, musical and iconographic ambitions amongst others. Even though these intentions were subsumed under the generic name ‘Sarah’ and were thought of as complementary, one may suggest that Sarah Records can be, if not complete, at least decipherable without, for instance, its auditory element. The liner notes accompanying the music releases, written indifferently by Haynes or Wadd, would be referred to by the label founders as their own (silent, written) ‘singles’. These typewritten cut-ups borrowed the aesthetics of diary entries or personal letters and were addressed to the fans of the label. The same ‘cut and paste’ aesthetics would also be prevalent in the Sarah fanzines and newsletters, and were often copied, in reverent homage, by fans of the label in their own fanzines. Sarah Records may be approached as an iconoclastic and multi-sensorial label, realized in a variety of tangible fragments.

The emphasis on the relentless production of carefully crafted artefacts is what makes Sarah Records an especially apt entry point into the material culture of music in the late twentieth century. The case of Sarah Records, a micro-independent record label, also allows us to reflect upon material culture and technologies of mass production as means of conveying extremely personal and politically marginal messages (see Dale 2008 on the politics of independent record labels). A heteroclite collection of artefacts were produced and disseminated during the label’s lifetime: these included ephemeras (such as fanzines, flexi-discs, postcards, pamphlets, posters, newsletters) and more durable objects (in the form of 7-inch, 10-inch and 12-inch vinyl records, cassettes, compact discs). These artefacts will be my main focus point throughout the chapter; the analysis, however, will by no means be limited to them but will rather encompass their context of production and dissemination as well as their reception. By using the term ‘artefact’, instead of the more neutral ‘object’ for instance, I will insist on a conception of the thing as that which is ‘made’ (Glassie 1999: 85). An emphasis on another term – for instance ‘good’ or ‘commodity’ – will lead to a conception of the thing as primarily that which is ‘traded and possessed’ (Glassie 1999: 85). Throughout this chapter, the emphasis will shift and hover between artefacts and goods, which represent not two irreconcilable realities but two interrelated dimensions of material culture and its study:

All things are artifacts, all are goods, and material culture study needs both orientations. The student of artifacts engages them as creations, blendings of nature and will, and slights use and commerce, avoiding the moral issues raised during contemplation of economic systems. The students of goods encounters things as commercial cyphers, slighting creators and avoiding the moral issues raised through consideration of systems of production. (Glassie 1999: 85)

Throughout the chapter I will rely on the artefacts produced by the Sarah label and complementary material sources (such as music fanzines of the same era, which directly refer to Sarah Records and whose existence was arguably prompted by the label). I will especially focus on the visual and tactile aspects of the material culture of music, examining the ways in which tangible artefacts may capture and solidify the everyday, thus allowing for its further material and oral dissemination. However, it should be noted that, unlike the material culture embraced by Glassie (which largely focuses on bygone handicrafts), ‘[t]he material culture of the everyday is largely unexplored territory because it lies too close at hand to intrigue, there is nothing tantalisingly exotic about the quotidian’ (Attfield 2000: 174). Yet, the passing of time defamiliarizes the everyday, and the (relatively) chronologically distant material culture of Sarah Records, characterized by disused formats, designs and aesthetics (signified by typewritten texts, Xerox photocopies, handwritten letters), has now been endowed with a form of exoticism which at the time was nearly imperceptible or indiscernible from contemporary productions.

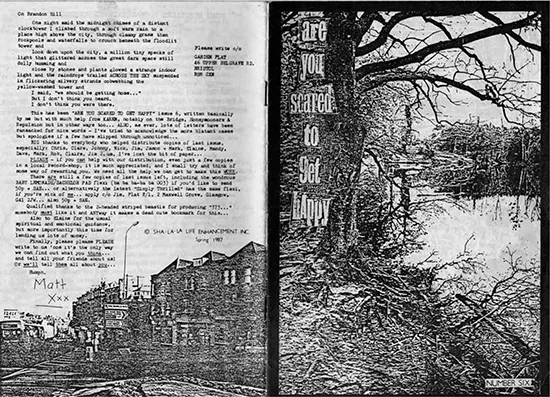

For instance, the fanzine Are You Scared To Get Happy?, written by Haynes in the years 1985–87, was initially an original, yet technically unremarkable, contribution to the fanzine production of the time (see Figure 1.1). On browsing the pages of the thin, A5-sized publications of the fanzine one is struck by their bright colours – the pages were photocopied in blue, red and green inks. The Xerox machine muddied the texts and the photographs, though beneath the colour noise, miniaturized reproductions of everyday documents and photographs can be recognized (issue number 6, written in May 1987, contains duplications of a Bristol map and a used bus ticket dated ‘17: 15 01NOV86’ as well of photographs of Bristol’s Brandon Hill Park and railway tracks). Type-written and handwritten strips of text are disorderly pasted upon the images. The articles of the fanzine typically deal with now-forgotten short-lived bands (such as The Bridge, Valerie, The Wildhouse, Whirl or Remember Fun), intercalated with more general pieces about music, and melancholic depictions of Bristol. Throughout the pages, Haynes also reproduces fragments from personal letters he receives. Readers were encouraged to write to him at ‘Garden Flat, 46 Upper Belgrave Road, Bristol BS8 2XN’, notably to exchange music. Haynes’ fanzines would come with flexi-disc 7-inch records. The flexi-disc is an explicit materialization of the fierce, DIY ethics expressed in the pages of the fanzine:

We want NOTHING to do with the ‘real’ record industry, this is our own pure personal POP vision … We distribute BY HAND too. It’d be nice – easier for us, certainly – to go through The Cartel,1 but that’d mean increasing the price and it’d just be the first step towards absorption in THE SYSTEM … . (Haynes 1987)

Figure 1.1 Are You Scared To Get Happy? #6, fanzine by Matt Haynes, published in 1987, © Matt Haynes 1987

The typewritten artefact is a clear indication of bygone, pre-digital writing technologies and the presence of Haynes’ postal address points to now marginalized modes of communication, as letter-writing has been largely replaced with e-mailing (Adams 2007: 185–99) and exchange of music is today realized online, notably through peer-to-peer websites (see Chapter 4). The production of Xerox photocopy machines has now been discontinued, as digital photocopiers have replaced them, whilst personal computers have supplanted typewriters in the daily process of writing. The flexi-disc itself may be retrospectively seized as a technological vestige whose handling is likely to provoke, amongst younger audiences especially, a feeling of perplexity and wonder. This can also be related to Benjamin’s perception of everyday, mechanically produced objects as susceptible to becoming extraordinary with the passing of time. Thus:

Benjamin proposed that everyday objects of industrial culture, particularly those entering a kind of twilight age in terms of their usefulness or attractiveness, could be rediscovered and rendered useful again in what he envisaged as a project of remembering and understanding the dynamics of the moment of their creation. (McRobbie 1993: 90)

Benjamin’s argument can productively be extended to the realm of past technologies. Vinyl records and fanzines function as formerly common objects which, upon rediscovery, trigger critical questioning. A salvaged copy of Are You Scared To Get Happy?, which encapsulates past technological realities, provides a tactile, visual and aural connection with the past. It seems that grasping (literally and figuratively) the everyday, or what makes the everyday, becomes possible the moment a former incarnation of the everyday has vanished or been transformed, thus existing as a detached form, as it were, available for observation. It is to the extent that the material culture of Sarah Records is no longer ordinary (as it has been detached from its context of creation, the record label does not exist anymore, the network which distributed it has collapsed, the internet privileges a culture of dematerialized objects over material artefacts) that it becomes easier to distinguish and reflect upon it. In other words, transient objects such as written artefacts or flexi-discs, should they have been preserved by collectors, may enter the category of durable objects. In his pioneering study of marginal materialities, Thompson has notably theorized the shift of status, which occurs in time, from neglected artefacts (or ‘rubbish’) to collectors’ items (1979). As shown by Thompson, the shift of status is largely anchored in discourse: redemption begins with words of redemption.

Furthermore, it may be argued that objects, in order to be legible, need to be thought of and articulated in the context of a more immaterial or untraceable practice. Sarah Records should thereby be approached as both a material and enduring reality and as a transient, open-ended story (see Roy 2014: 63–76). The record label can benefit from being related to earlier artistic ventures such as Paris-based Situationism (1957–72), with which it shares certain affinities. Situationism was notably characterized by ceaseless explorations and reinventions of the city and the making of new cartographies of the city, revealed through the dérive (‘drift’) or the art of being lost. If the Situationists (contrary to the founders of Sarah Records) rejected a priori the notions of material traces, revelling in being idle, free and untraceable ‘lost children’, they also constantly produced self-released and self-distributed newsletters, journals and pamphlets. This important production clearly contradicts their aspirations to be invisible and forgotten. The Situationists, who ceaselessly professed the will to be forgotten and anonymous, found in Guy Debord a name and a most memorable incarnation. The quantity of artefacts they produced prevented the oblivion and complete disaggregation of the movement. Similarly, the Sarah label existed both as an impalpable, fluid story and as a tangible territory of objects, as if to show that, in the words of Benjamin, ‘to live is to leave traces’ (1973: 29, my emphasis). The most iconic trace of the Sarah label was the last Sarah newsletter (entitled ‘A Day for Destroying Things’), which was reproduced in the advertisement pages of two music magazines (Melody Maker and New Musical Express) in August 1995. ‘A Day for Destroying Things’ offers strong textual and aesthetic resonances with Situationist ideas, as it incited fans of the label to forget Sarah and ‘erase the traces’ of the label. The example of Sarah Records, as well as Situationism, draws our attention to the paradox between living and producing traces or documents.

Playing the Sarah Label: A Practice of the Everyday

THE SAROPOLY GAME: A METAPHOR FOR THE SARAH LABEL

In September 1991, Sarah 050 was released and distributed via the Cartel. The artefact, however, was not a record or a music fanzine. Sarah 050 was a game, a ‘Saropoly’ (a portmanteau word for Sarah and Monopoly) parodying the well-known board game designed by the Parker Brothers in 1934. The city miniaturized and represented on the Saropoly board was not London (as in the official British version of the game) but Bristol. Fanzine-writer Alistair Fitchett remembers that the ‘Saropoly was a board game in which you pretended to be a record company mogul dashing around a “virtual” city of Bristol … collecting all the items essential to make a … Sarah 7′ single in a plastic bag’ (Fitchett 1997). In the pamphlet Les Lèvres Nues #8, published in May 1956, Debord and Wolman distinguished between two main categories of détournement, namely ‘minor détournement’ (‘the détournement of something which has no importance in itself and which thus draws all its meaning from the new context in which it has been placed’) and ‘deceptive détournement’ (‘the détournement of an intrinsically significant element, which derives a different scope from the new context’). The Saropoly game has to be thought of as a deceptive détournement. I will take the Saropoly game as an operative metaphor of the label. As Tilley remarks, ‘[m]etaphor provides a ...