This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection of fifteen essays looks at the theme of decadence and its recurring manifestations in European literature and literary criticism from medieval times to the present day. Various definitions of the term are explored, including the notion of decadence as physical decay. Some of the essays draw parallels between modernist and postmodernist notions of decadence. Similarities are detected between fin de siècle decadence at the end of the nineteenth century (which reaches its apotheosis in the character of Eugene Wrayburn in Our Mutual Friend) and depictions of decadence in our own age as we enter the new millennium.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Romancing Decay by Michael St John in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism for Comparative Literature. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Redeeming the Decadent City: Changing Responses to the Urban and Wilderness Environments in the Lives of St Jerome*

Introduction: decadence and the city

From ancient times, decadence has been seen as a characteristically urban vice. Evidence of the antiquity of the association between decadence and city life can be found in the Book of Genesis, which tells how the first city was established by Cain, the first murderer, on whose forehead - as a sign of his irreparably corrupt and fallen nature - God is said to have placed a mark of shame (Genesis 4: 15-17). Writing at the beginning of the fifth century of the Common Era, and following a tradition of both Jewish and Christian legend which regarded Cain as the founder of a race of degenerate evildoers, St Augustine drew upon the strongly antagonistic view of urban civilization evident in the Book of Genesis when he identified Cain’s city with the ‘City of Man’, an allegorical place whose inhabitants consisted of those men and women whom God had condemned to suffer eternal damnation.1 However, although Augustine’s writings betray a deep distrust of the wickedness and depravity of urban life - for instance, he wryly noted that Rome, like the city of Cain, was founded by a fratricide (City of God, Book XV, Chapter 5) - his attitude towards cities was nonetheless ambivalent, for not only did he choose to represent Hell and damnation in terms of urban civilization, but he also conceived of the Heavenly kingdom as a city:

I classify the human race into two branches: the one consists of those who live by human standards, the other of those who live according to God’s will. I also call these two classes the two cities, speaking allegorically. By two cities I mean two societies of human beings, one of which is predestined to reign with God for all eternity, the other doomed to undergo eternal punishment with the Devil.2

The idea of the City of God - like that of the City of Man - has its origins in the Bible, not least in the new Jerusalem of the Book of Revelation, while Augustine himself indicated that its direct source was Psalm 87: ‘Glorious things are spoken of thee, O city of God’ (Psalm 87: 3). But Augustine’s belief that Heaven could best be understood as a city no doubt also reflects the very great extent to which his cultural and intellectual outlook was moulded by the civic values of classical Greece and Rome. The city stood at the very centre of classical civilization. According to Aristotle: ‘man is by nature a political animal’, that is, one who participates fully in the life of the city (polis).3 Thus, it is possible to discern both in the work of Augustine, and in the wider cultural milieu from which he drew, two contradictory attitudes towards city life. On the one hand, Augustine saw the city as the arena within which human civilization was best able to flourish, the place where all that was most noble in human nature could be realized, while on the other hand he was profoundly suspicious of the worldliness and hedonism that were so much a part of urban existence.

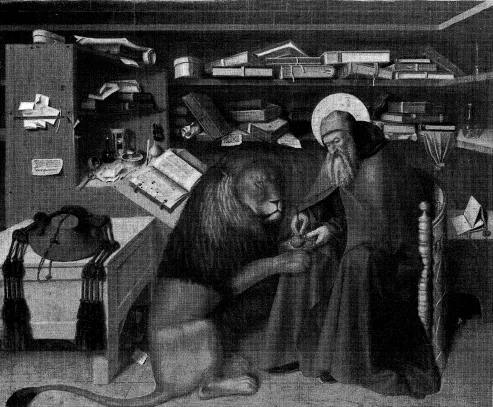

Of course, each of these two views of the city carries with it a corresponding set of beliefs and assumptions about that which is not the city: the countryside or wilderness. To those who look favourably upon the city, the country can be seen as a rustic backwater that knows nothing of the great cultural achievements of human civilization such as philosophy and art. Alternatively, the country can be viewed as a pastoral idyll that has remained relatively untouched by the decadence and corruption of the city - a place that has thus managed to preserve something of the primal innocence of humanity.4 In this essay, I shall explore these different responses to the country and the city by examining how urban existence was represented in the Life and work of Augustine’s great contemporary, St Jerome, both in his writings and in the legendary stories that subsequently came to be told about him. As a point of entry into this material, I shall concentrate upon the painting of St Jerome and the Lion that was undertaken in the middle of the fifteenth century by the Neapolitan artist Niccolò Colantonio (Plate 1). By comparing its treatment of the themes of the city and the wilderness with Jerome’s professed views on these subjects, it will be possible to reflect upon the ways in which attitudes towards the urban and wilderness environments altered over the course of the Middle Ages.5

St Jerome: life and legend

Jerome was born during the middle of the fourth century at Stridon in Dalmatia (the exact date of his birth is unknown, but modern scholars estimate that it was some time between 331 and 347), and his greatest contribution to history, and the achievement for which he was most revered during the ensuing Christian centuries, was his production of a Latin translation of the Bible (which became known as the editio vulgata, the Vulgate or popular edition), a text that for almost a thousand years, and throughout the Latin-speaking West, was regarded as the standard version of the Scriptures.6 However, in addition to his skills as a linguist, scholar, and translator, Jerome was also famed for his advocacy of the monastic life (a life that he himself practised, first in solitude in the Syrian desert, and then as the leader of a community of monks at Bethlehem in Palestine), and it is while he was residing in Bethlehem during the second phase of his monastic career that his miraculous encounter with the lion is supposed to have taken place.7

1 Niccolò Colantonio, St Jerome and the Lion (c. 1445), Naples: National Museum of Capodimonte

Jerome’s extensive writings, and in particular the many letters that he wrote to his friends (and enemies), are full of personal information about his life and work, and these scattered autobiographical references - along with testimonials to his character from such eminent figures as St Augustine, Sulpicius Severus, Gregory the Great, and Isidore of Seville - were the sources from which two ninth-century Latin Lives of the saint were compiled. These Lives, written independently of one another by anonymous authors, are known as Hieronymus noster and Plerosque nimirum, and were in turn used as sources for all of the subsequent medieval biographies of Jerome.8 However, as well as recording the known facts of Jerome’s life, the author of Plerosque nimirum also included in his narrative the legendary story of the saint’s encounter with the lion, a tale that had previously been told in relation to a near-contemporary of Jerome - the Palestinian abbot St Gerasimus - by John Moschus in his seventh-century collection of the lives of the desert fathers, the Pratum Spirituale.9

Colantonio’s St Jerome and the Lion

According to the author of Plerosque nimirum, the encounter between Jerome and the lion took place one evening while the saint was listening to the sacred lessons with his fellow monks in the monastery that he had established at Bethlehem. A lion suddenly came limping into the building, whereupon everyone fled except for Jerome, who confidently approached the animal as though he were welcoming an honoured guest. The lion showed Jerome his paw, and seeing that the creature was badly injured the saint summoned his brothers and instructed them to wash and bind the wound with care. As the monks were performing this task they observed that the lion’s paw had been scratched and torn by thorns, but they washed and dressed the wound so carefully that they were able to restore the animal to full health. From then onwards the lion lost all traces of his former wildness, and lived tamely alongside the monks, helping them with their labours.

The story of Jerome and the lion was widely disseminated in the late Middle Ages thanks to its inclusion in two of the most popular and influential books of the thirteenth century; Vincent of Beauvais’s Speculum Historiale, an account -completed in 1244 - of the history of humanity from the Fall to Vincent’s own lifetime, and the Legenda Aurea, a collection of saints lives written by Jacobus of Voragine, the Archbishop of Genoa, which dates from about 1260.10 However, the popularity of the story was not simply confined to the medium of literature; it is also reflected in the field of the visual arts. According to the art historian Grete Ring, Jerome was perhaps ‘the most frequently represented saint in art from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, with the exception of the members of the Holy Family and St John’.11 Although a number of different episodes from the legend of St Jerome not involving the lion formed the subject of some of these fourteenth-, fifteenth- and sixteenth-century representations, the saint was most commonly shown dressed as a cardinal and seated on a chair in his study (or on a rock in the wilderness), either removing the thorn from the lion’s paw, or reading a book with the animal lying quietly at his feet.12

The eminent Italian canonist Joannes Andreae, who taught law at the University of Bologna from 1301 until his death in 1348, and who commissioned a number of paintings of Jerome, is usually credited with introducing the motif of the lion into the visual arts, and combining it with images of the saint as a scholar and theologian.13 In his book Hieronymianus or De Laudibus Sancti Hieronymi, Joannes wrote:

I have also established the way he should be painted, namely, sitting in a chair, beside him the hat that cardinals wear nowadays (that is, the red hat or galerus ruber) and at his feet the tame lion; and I have caused many pictures of this sort to be set up in divers places.14

The painting of St Jerome and the Lion by Colantonio perfectly accords with Joannes’s prescriptions, and is one of the best-known, and most interesting, artistic treatments of the subject. The painting is dominated by the figures of Jerome and the lion, both of whom are situated in the centre of the composition, and Colantonio successfully managed to convey not only a sense of the benevolence of the saint and the pathos of the injured animal, but also a strong feeling of trust and companionship between the two. However, the picture is also remarkable for the extraordinary detail with which it represents the interior of Jerome’s cell.15 The shelves are strewn with books, pens and papers, along with all of the other equipment that one would expect to find in a scholar’s study, while the book that is lying open on Jerome’s desk, and the general atmosphere of disorderly clutter, gives the impression that the saint had been busy at work when the lion entered his room, seeking his help. Jerome himself is seated on an ornately carved chair. He is dressed in a brown habit and cloak, and is wearing a tightly fitting grey hat, while his tasselled, red cardinal’s hat, the galerus ruber, is prominently displayed to the left of the lion, on a table in front of his desk. Finally, in the bottom right-hand corner of the painting, behind Jerome’s chair, a mouse can be seen eating a scrap of paper.

Amidst all the finely observed detail of Jerome’s study, the lion remains a somewhat incongruous, almost enigmatic figure. In spite of the animal’s large size and enormously powerful frame, he is stripped of the conventional leonine attributes of wildness and courage, and is pictured instead with a slightly mournful and subdued expression, looking rather ill at ease in the domestic setting of Jerome’s book-lined chamber. The lion’s former wildness stands in stark contrast to his present domesticity, and the encroachment of the animal into the indoor, human space of Jerome’s study seems to blur the traditional opposition between the concepts of ‘nature’ and ‘culture’, ‘wilderness’ and ‘civilization’, and ‘wild’ and ‘tame’. Moreover, Jerome’s evident sympathy for the predicament of the lion, and the proximity and intimacy of the two, threatens to dissolve still further the conventional boundaries separating the human and animal worlds.

It is significant that in contrast to the literary version of the story found in Plerosque nimirum, Colantonio chose to locate the action not in one of the monastery’s public, communal areas, but in the private space of Jerome’s study, a setting that enabled him to depict an impressive array of books and papers in the background of the painting. Furthermore, rather than following Plerosque nimirum and portraying a scene in which Jerome at first examined the lion’s wound, and then delegated the task of washing and dressing it to his monks, Colantonio showed the saint actually removing the thorn from the animal’s paw. (According to Plerosque nimirum, the lion did not have a thorn stuck in his paw, but merely a wound that he had received when his paw had been pierced with thorns.) The effect of these two changes was to simplify the narrative while simultaneously amplifying the role that Jerome played in it. By removing the other monks from the scene, and so making Jerome solely responsible for healing the lion, Colantonio eliminated all the superfluous elements of the story that could divert attention from the saint, and reduce not just the dramatic impact of the miracle that he performed, but also the strength of the bond connecting him to the lion. With great narrative economy, then, Colantonio was able in the one painting to convey two quite distinct images or impressions of Jerome. On the one hand, he depicted a popular animal story in which a genuine sense of intimacy and companionship between the human and animal protagonists was conveyed, while at the same time he projected an image of the saint as a great scholar and theologian - reminding his audience of Jerome’s reputation for erudition through the expedient of locating the action in his study.

Of course, in addition to these two aspects of Jerome’s life and character, Colantonio - following the artistic convention established by Joannes Andreae -also represented the saint as a cardinal, displaying his red cardinal’s hat on the table situated in front of his desk. In the same way that the books and papers lining the shelves of Jerome’s study lend intellectual weight to the portrait, so the presence of the galerus ruber invests the figure of the saint with considerable ecclesiastical authority, denoting as it does the important position that he was thought to have occupied in the governing hierarchy of the Church. However, it is important to note that the institution of the college of cardinals was not actually established until the eleventh century, over six hundred years after Jerome’s death, and it was not until the Council of Ly...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Redeeming the Decadent City: Changing Responses to the Urban and Wilderness Environments in the Lives of St Jerome

- 2 Nature, Venus, and Royal Decadence: Political Theory and Political Practice in Chaucer’s Parliament of Fowls

- 3 Reading Symptoms of Decadence in Ford’s ’Tis Pity Shes a Whore

- 4 ‘Bawdy in Thoughts, precise in Words’: Decadence, Divinity and Dissent in the Restoration

- 5 Dickensian Decadents

- 6 Defining Decadence in Nineteenth-century French and British Criticism

- 7 Somewhere there’s Music: John Meade Falkner’s The Lost Stradivarius

- 8 ‘Squalid Arguments’: Decadence, Reform, and the Colonial Vision in Kipling’s The Five Nations

- 9 The Metamorphoses of a Fairy-Tale: Quillard, D’ Annunzio and The Girl With Cut-Off Hands

- 10 A Passion for Dismemberment: Gabriele d’ Annunzio’s Portrayals of Women

- 11 The Escape from Decadence: British Travel Literature on the Balkans 1900–45

- 12 Books and Ruins: Abject Decadence in Gide and Mann

- 13 Resisting Decadence: Literary Criticism as a Corrective to Low Culture and High Science in the Work of I. A. Richards

- 14 Blow It Up and Start All Over Again: Second World War Apocalypse Fiction and the Decadence of Modernity

- 15 Decadence and Transition in the Fiction of Antonio Tabucchi: a Reading of Il filo dell’orizzonte

- 16 Beyond Decadence: Huysmans, Wilde, Baudrillard and Postmodern Culture

- 17 Translation: Decadence or Survival of the Original?

- 18 The Decadent University: Narratives of Decay and the Future of Higher Education

- 19 The Lateness of the World, or How to Leave the Twentieth Century

- Bibliography

- Index