![]()

1 Asia and the middle-income trap

An overview

Francis E. Hutchinson and Sanchita Basu Das

Much has been said about this being the Asian Century, with global growth increasingly being driven by China, India and the South East Asian economies of Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam. Its dynamism, openness to trade and aggressive export production have shifted the economic ‘weight’ of the globe towards Asia.

While Asia accounted for a mere 19 per cent of the global economy in 1950, by 2010 it accounted for 28 per cent. This rapid expansion has been due to the widespread adoption of three common policies by countries across the region: export-oriented industrialization; heavy investment in education; and focus on long-term growth (ADB, 2011).

As a result, Asia is on course to regain its historic position as the most important region in the global economy. Looking forward, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) predicts that, if the region retains its competitiveness, by 2050, Asia could generate 52 per cent of global GDP, and its residents could enjoy an average per capita income of $40,800 in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms – a level similar to Europe’s current income level (ADB, 2011).

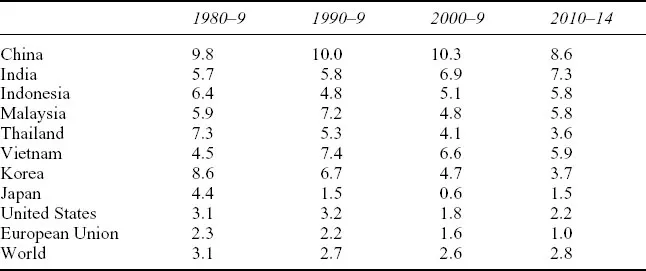

Recent economic trends support this scenario. Indeed, since the turn of the century, the fortunes of emerging Asian economies stand in stark contrast to those of mature economies (Table 1.1). Since 2000, the United States and the European Union have experienced anaemic growth, with growth rates at or below 2 per cent per annum. For its part, China grew at 10.3 per cent per annum from 2000 to 2009 and 8.6 per cent from 2010 to 2014. India grew at 6.9 per cent and 7.3 per cent over the same periods, respectively. Other key economies in the region, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam, grew at 5 per cent per annum or more post 2000.

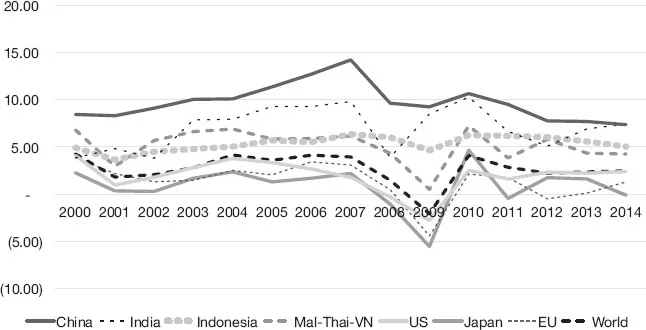

Not only are the average growth rates in the emerging Asian economies significantly higher than the global mean, as well as mature economies in aggregate, but also their growth is more resilient. Having learned the hard lessons of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, economies in the region have worked hard to maintain strong economic fundamentals and ensure that macro-prudential policies are in place. In 2009, at the height of the Global Financial Crisis, the world economy contracted 2.1 per cent (Figure 1.1). While the advanced economies of the United States, the European Union and Japan experienced prolonged downturns, the emerging economies of China, India and South East Asia largely sustained their growth rates, albeit with a brief dip.

Table 1.1 GDP growth, 1980–2014 (annual percentage change)

Source: WDI Online, constant local currency.

Figure 1.1 GDP growth, 2000–14 (annual percentage change)

Sources: World Bank National Accounts data and OECD National Accounts data files.

Notwithstanding recent performance, future growth is not guaranteed. Despite high levels of growth, there are indications that these economies are slowing. Although China has averaged growth rates at or near 10 per cent per annum since 1980, its economy’s momentum has decreased, with growth falling to less than 8 per cent per annum in 2011–14. India, for its part, has long performed erratically, alternating between growth at 4 per cent and bursts at 8 per cent per annum. And, while the South East Asian ‘Tiger’ economies of Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand have also experienced good growth, it has not been at the levels seen before the Asian Financial Crisis. In the period 1990–7, these economies grew at an average of 7.6, 9.2 and 7.4 per cent, respectively. In 2011–14, the respective growth rates for these economies were 5.7, 5.4 and 2.5 per cent (WDI Online).

This has prompted introspection and questioning among policymakers about the way forward. Initially, growth comes from the inter-sectoral reallocation of factors of production, with faster growth of output and employment in industry than in agriculture. This is more productive in aggregate terms, and allows economies of scale through specialization and the acquisition of technological capabilities. Industrial activities have the potential for multiplier effects in the economy, through the demand for downstream and upstream suppliers (Kaldor, 1978).

By basing this industrialization process on export production and an initial focus on low value-added and high-volume assembly operations for export, countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia and China become part of production networks across the region. Over time, these countries have been able to make some progress at climbing the value chain through upgrading products and processes (World Bank, 2010). This has been termed the ‘easy’ phase of growth.

This economic model – referred to as ‘Factory Asia’ by the ADB (2013b) – has enabled those countries adopting it to benefit from sustained increases in per capita income. In 1980, Malaysia, Thailand and Indonesia had per capita incomes of US$1,803, US$683 and US$536, respectively. By 2014, the corresponding figures were US$10,830 (for Malaysia), US$5,561 (Thailand) and US$3,315 (Indonesia), representing a more than fourfold increase in each case. China, for its part, has done even better, with its per capita income level increasing from US$193 in 1980 to US$7,594 in 2014 (WDI Online).

This stage of growth is, however, finite. At some point, the reserve army of labour in each of these countries is – or will be – exhausted. Wages subsequently rise and, if this is not accompanied by commensurate increases in productivity and technological progress, these countries will become uncompetitive.

Indeed, there are signs that this transition may not be happening. Relative to countries of similar income in other parts of the world – and particularly the high-income Asian economies of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan – innovation levels in the middle-income countries of Asia are below par (World Bank, 2010). There are also concerns about the availability and quality of human capital in China and key South East Asian economies (Fang and Yang, 2013; Jimenez et al., 2013; Raya and Suryadarma, 2013).

This situation is commonly referred to as the ‘middle-income trap’. The trap, insofar as it can be so termed, refers to countries that have reached a certain level of per capita income on the basis of labour-intensive tasks and are struggling to transition towards more skill-intensive and sophisticated activities. Unable to compete with lower-cost locations in mature sectors, yet not possessing sufficient skill or technological capabilities to perform high value-added and well-remunerated tasks, they are likely to stagnate economically. This issue is best exemplified by one statistic. According to the World Bank, only 13 of 101 countries classified as middle income in 1960 have subsequently been able to attain high-income status. In East Asia, this group is thus far limited to Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore (World Bank, 2013: 12).

Barring these five countries, the rest in the region – including high performers such as Malaysia, Thailand, China and Indonesia – are still in the middle-income bracket. Faced with slowing growth rates, increasing wage levels and below par innovation in these and other countries, policymakers have deliberated intensively about how to make the transition from labour- and capital-intensive growth to productivity- and technology-driven growth. Given the difficulty in attaining high-income status, the debate has arisen about whether there is something qualitatively different about this transition.

Thus, the middle-income trap debate is about the appropriate institutional and policy settings for middle-income countries to enable them to continue to grow past the ‘easy’ phase of economic growth. However, there is disagreement regarding the validity of the concept, the best term to use and whether there are also other traps for countries at other levels of income. The MIT debate is further complicated by often contradictory advice, formulated on the basis of cross-country regressions with different parameters and variables.

The MIT and the debates surrounding it are the focus of this book. We thus ask the following questions: what is the middle-income trap and how can it best be defined? What can we learn from the countries that have been able to ‘escape’ the trap to attain high-income status? How are the biggest emerging economies in Asia currently grappling with the challenges of transitioning from labour-intensive to technology- and knowledge-intensive production? Which institutional factors and policies enable the shift to higher and qualitatively better growth?

This book is divided into four parts. The first part looks at the conceptual under-pinnings of the MIT, particularly where the concept originated, how it should be defined and to what groups of countries it applies. The second seeks to learn from success, particularly the experience of high-performing Asian economies, and tries to identify distinctive characteristics of their growth experience. The third part looks at the three largest emerging countries in Asia to understand the challenges they face in making the transition towards productivity- and technology-driven growth. The fourth and final part examines the determinants of growth – in particular: institutional quality; the availability and quality of human capital; and policies affecting trade and investment and their implications for innovation.

Conceptual underpinnings

While the term ‘middle-income trap’ has been successful at attracting the attention of policymakers, it has also given rise to a range of different definitions, methods of measurement and countries to which it is taken to refer. It is thus helpful to look at the origins of the concept and the approaches taken to study it in order to clarify ambiguities.

In 2004, Garrett wrote about globalization’s ‘missing middle’. He argued that globalization processes have benefited wealthier countries whose institutions and human capital bases encourage innovation, as well as poorer nations that focus on routine tasks and utilize easily available technology at low costs. However, countries in the middle, with higher labour costs and imperfect institutional configurations, have not benefited as much. Trapped between countries at the technological frontier, such as the United States on the one hand and low-cost providers such as China on the other, middle-income countries are faced with decreasing opportunities. In order to survive, they need to implement far-reaching reforms in areas such as finance, government and legal systems in order to encourage innovation.

In their 2007 work, An East Asian Renaissance, Gill and Kharas develop the challenges facing the ‘missing middle’. They argue that, contrary to expectations, East Asia recovered quickly from the Asian Financial Crisis. The region’s capital markets developed quickly, poverty decreased substantially and the middle class expanded substantially. As a result, they contend that East Asia is increasingly a middle-income region and, consequently, has a number of countries that could attain high-income status. However, middle-income countries find it difficult to maintain high growth rates and, consequently, must seek to alter the way they do things. In particular, this group of countries will need to: become more specialized in terms of what it produces; shift from investment-driven to innovation-driven growth; and produce workers able to innovate in the workplace. If this transition does not occur, middle-income countries will be ‘squeezed between the low-wage poor-country competitors that dominate in mature industries and the rich-country innovators that dominate in industries undergoing rapid technological change’ (Gill and Kharas, 2007: 5).

Perhaps more than any other publication, An East Asian Renaissance served to bring the MIT to the attention of policymakers. However, while intuitively appealing, this is not an uncontested concept. The Economist (2013) famously labelled the issue as ‘claptrap’, arguing that policies should just focus on leveraging a country’s comparative advantage. The periodical argues not that competitiveness is a dichotomy of labour-intensive or skill-intensive activities, but rather that economies operate along a continuum, and competitiveness is determined at a given price point. Furthermore, the transition from labour-intensive to knowledge-intensive production is a continuous process, but most probably a disruptive one.

This position has considerable merit. Yet, if simply focusing on a given country’s comparative advantage were sufficient for growth to occur – albeit at slower rates as it became wealthier – and the transition from labour-intensive to knowledge-intensive production was continuous, surely more countries would have ‘graduated’ to high-income status over the past five decades. The fact that only a small minority has done so suggests that this process is not automatic, and that growth past a certain threshold is more difficult.

Following widespread discussion of the MIT, a significant volume of research has been carried out to define and measure the concept. In terms of definitions, there are two approaches. First, one can use international income standards to identify those countries that classify as middle income and then try to specify thresholds or performance indicators that indicate whether they have ‘graduated’ to high-income levels or have failed to do so – thus falling into a ‘trap’. Alternatively, one can look at countries seeking to transition from labour-intensive to knowledge-intensive tasks and analyze the policy challenges they face.

With regard to income thresholds, the World Bank sets out low-, middle- and high-income categories (World Bank, 2015a).1 In 2015, low-income countries referred to those with a per capita income of US$1,045 or less; middle-income economies were those with per capita income of between US$1,045 and US$12,746; and high-income economies included those with per capita income above US$12,746. However, given that the middle-income bracket spans US$1,045 to US$12,746, many have questioned the utility of a category that is so expansive.

Middle-income countries are further split into two at a threshold of US$4,125. Those below this income are lower middle income, and those above it are upper middle income. Many, but not all, of the countries associated with the middle-income trap debate – such as Malaysia, Thailand and China – belong in the upper middle-income category. These countries have enjoyed rapid and more sustained growth than have exemplars of the MIT from other regions. For example, Brazil and Mexico are also said to be in the trap, but they attained middle-income status in the 1980s and have remained there since.

Felipe et al. (2012) look at the pace at which countries grow and move from one income category to the other. As with the World Bank, they identify four groups by GDP per capita: low income; lower middle income; upper middle income; and high income. However, unlike the World Bank, which regularly updates its definitions, the specific thresholds are held constant over time. Based on cross-country comparisons, and particularly the trajectory of high-performing economies, Felipe et al. then specify how long a given country should take to pass from middle income to high income. Those countries that are unable to ‘graduate’ to high income within this time frame are taken to be in the middle-income trap. Based on this, they conclude that a country is in the lower middle-income trap if it has been in that category for 28 years or more; and that it is in the upper middle-income trap if it has been in that category for 14 years or more.

Along a similar vein, Eichengreen et al. (2013) argue that the middle-income trap can be understood as a slowdown in growth after a specific threshold. This is counter to the conventional convergence hypothesis, which holds that economies will slow gradually as they grow richer and move closer to the technological frontier. Instead, Eichengreen et al. contend that there are specific levels of per capita income at which economies slow. Defining a slowdown as a decrease in growth of at least 2 per cent over two consecutive and non-overlapping seven-year periods, they examine episodes of slowdowns in previously rapidly growing middle-income economies. They find that, rather than one specific point, there are two levels – one at approximately US$10–11,000 and another at US$15–16,000 (in 2005 PPP dollars) – where growth slowdowns are more frequent. This means that a larger group of countries is at risk of slowdown and at a lower level of income than previously thought.

While absolute and relative income thresholds are important, another approach is to focus on the structural issues that most middle-income economies face in their transition away from factor-driven growth to innovation-driven growth. Thus, the Commission on Growth and Develo...