![]()

1

Introduction

On the evening of Wednesday 16 September 1959, the Roman Catholic parishioners of St Gregory the Great at South Ruislip in London gathered in their local primary school hall to hear their parish priest, Philip Dayer, describe his plans for the parish. Dayer’s speech provides an insight into the thoughts of a priest charged with founding a new parish.1 He had been appointed the year before by the archbishop of Westminster, William Godfrey, and had converted the garage of the house he acquired into a chapel.2 Dayer insisted that the primary aim of the fledgling parish was to build a church.

For thousands of years, the PARISH has been the unit within the Catholic Church by means of which its great mission of applying the fruits of Christ’s redemption is brought about. A parish should have its Church – the focal point of worship where the sacrifice of Calvary is renewed day by day. It should have its font which gives birth to new children of God. The parish is a social unit, a family with a Father, it shows itself visibly as an entity. … Until we have built our own Church we will not have reached our highest goal.3

In this short statement of the vital connection between the church building and the institutional Church lies the central argument of this book.

The church building presents an image of the institutional Church, and, at the same time, when a congregation gathers within it for worship, it also constitutes the reality and local manifestation of that institution. This is not a new interpretation: it was an important idea in the mid-twentieth century when the churches in this book were built.4 The church building is therefore a physical space which is also the social space of an institution, where that institution takes shape. Dayer’s speech to his parishioners in South Ruislip emphasised this conjunction: worship, he said, is the ‘focal point’ of the parish and takes place in the church; the font, a designed object within the building, ‘gives birth’ to new members of the parish, reproducing and sustaining the Church; the ‘family’ of the parish, the ‘unit’ of the Church, ‘shows itself’ in the building.

The parish not only shows itself in the building, however, it is also constructed with it. The church is a social space produced by human reason and activity. The purpose of Dayer’s speech, after all, was to urge his parishioners to give money and time towards the construction of both the social and physical fabric of this unit of the Church. In this book I accept the premise that ‘(social) space is a (social) product’, constructed by people for the purpose of maintaining a model of social relations; space is not a neutral container, but ‘a tool of thought and of action’.5 As a tool, it is made. Social spaces are produced by many varied agents and influences. The institutional Church is produced in a new context, by different people, and therefore in distinctive forms each time a church building is constructed.

SOCIAL AND URBAN CONTEXTS

The wider context for the church of St Gregory explains its presence and form. Before Dayer was sent to South Ruislip in 1958, Roman Catholics in the area attended a pre-war church in Eastcote, half an hour’s walk away. After the Second World War, a scout hut was adopted as a chapel for South Ruislip, served by a priest from Eastcote.6 The reason for this new foundation was a significant expansion of the population southwards into formerly rural South Ruislip as new housing developments continued throughout the 1930s and into the 1950s. Most was private suburban development, but there was also a local authority housing scheme. In Ruislip as a whole, the population rose from 16,000 in 1931 to 68,000 in 1951 and continued to grow.7 The new parish therefore met a pressing need to serve a substantial new population. This was a period of massive population shifts overseen by the state, including vast new suburban housing estates surrounding cities, radical inner-city developments and the planning of entirely new towns. The Church followed and responded to these movements with programmes of new building.

The demand for new churches also resulted from the social context of the Church in Britain. Catholicism in Britain was largely a result of immigration, above all from Ireland, beginning in the nineteenth century and continuing throughout the twentieth. The decade of the 1950s was a period of peak immigration from Ireland and Europe as the post-war welfare state and recovering industries demanded labour.8 Meanwhile earlier generations of Irish immigrants had settled and established themselves in British society. Amongst Roman Catholics the rate of church attendance was extremely high, much higher than in other denominations, and the numbers attending church were increasing, peaking around 1960.9 Since it was not until the 1970s that a serious decline in religious practice set in, the period leading up to this point, explored in this book, was one of enthusiastic optimism within the Church and apparent fervour amongst a burgeoning faithful.

Like other parishes that built new churches in the 1950s and 1960s, the parish of St Gregory was created because of population flows, themselves produced by cultural, economic and political circumstances, movements at a national scale that were particularly visible in parishes located in new areas of rapidly changing and expanding cities. As city authorities channelled and shaped this population movement, urban planning became an important factor in the production of the space of the church. The Roman Catholic church building was therefore tied to the development of a modern Britain.

CHURCH AS INSTITUTION

Following the parishioners’ meeting in 1959, the parish priest of St Gregory organised its campaign for a new church. Soon they were ready to build, commissioning architect Gerard Goalen to provide plans and a model in 1965. The Archdiocese of Westminster had to give approval to these plans before they could proceed. The Roman Catholic Church itself was therefore another agent in this production of the space of the church, in two ways: firstly, in its practical organisation and provision of the means for building churches, as a patron; and secondly, in the effects of its changing principles, through an institutional discourse. The Church combined a centralised authority in the Vatican with local levels of power. The Vatican supplied both universal regulations and more general guidance, regulating the forms that churches could take. The hierarchy of bishops served a national area: England and Wales were combined and Scotland had its own bishops’ conference; Ireland and Northern Ireland, not covered by this book, were governed by a single separate hierarchy.10 The parish formed the smallest unit administered by the priest and his assistants, or curates. Both the founding of a parish and the building of a church were initiated by the parish priest and decided by the diocese. At South Ruislip, the Archdiocese of Westminster monitored the progress of the new church of St Gregory. At a meeting in 1965, Goalen arrived to present his plans for the church, and they were referred to the archbishop of Westminster for his personal approval.11 While the diocese and the bishop authorised the building, members of the parish had to pay for it themselves. This is why Dayer was so keen to rally his flock and encourage their efforts.

One reason that South Ruislip could begin building in 1965 was that it did not have to pay for it all at once. To raise support for the building, Dayer issued a leaflet to his parish with an encouraging preface from Archbishop John C. Heenan explaining in detail how the building would be funded and proposing that every family commit to a weekly offering.12 Around half the estimated cost of £55,000 was to be met with a loan. Like many parishes and dioceses at this time, South Ruislip benefited from the general prosperity of this period, when credit was relatively easy to obtain. From the end of the Second World War until the mid-1950s, it had been difficult to build new churches because all building was strictly rationed by the government: building licences ensured that scarce materials and labour were reserved for the highest priority buildings, while churches were low on the scale, classed with ‘sports and entertainments’.13 Restrictions finally eased in the mid-1950s, and Catholics grasped the opportunity, with hundreds – probably well over a thousand – new church buildings undertaken in the period considered here: one clergyman estimated that in the 1960s in England and Wales alone, 600 new Catholic churches had been built.14 By the late 1960s and early 1970s, new building slowed and existing projects stalled as interest rates rose. Credit was squeezed in the late 1960s, and one of the worst financial crises of the twentieth century ensued as the 1970s began. The later part of the period was inevitably marked by a lull in church building. The period of two decades until that time witnessed a boom in the construction of new churches, stimulated by loans and absorbing substantial capital from across the Church.

The Roman Catholic Church influenced the form of its church buildings through its written teachings and the wide-ranging discourse of commentary that surrounded them. New ideas in theology were so rapidly disseminated that within a few years they could have an impact on the experiences of a churchgoer in a London suburb. One of the most important reasons for examining the period ten years either side of 1965 is that this year marked the closing of the Second Vatican Council. The council consisted of a series of gatherings in Rome, beginning in 1962, at which all the bishops of the world revised and approved documents that had been prepared by committees of theologians. These documents summarised the doctrine of the Church in a way that was meant to be relevant to the modern world, responding to new theological ideas and liturgical practices that had developed in the century or so before. Many of the council’s statements in such important areas as the liturgical rites and the nature of the Church marked an acceptance of new theological tendencies and had striking implications for how the Church’s members should conduct themselves and understand their role. The ideas behind the documents of Vatican II were not new, and their impact had already been felt. Yet the effects of the council were swift and highly visible, above all as a radical reform of liturgy took place in the years immediately after it, transforming the daily practices of the faithful.

This reform principally concerned the Mass. The Church wanted to encourage the ‘active participation’ of the congregation in liturgy, as the Mass was increasingly interpreted as the communal worship of the Church rather than a ritual performed mainly by a priest. Before about 1960, the Mass was said throughout the Roman Catholic Church in the West predominantly in Latin, the congregation’s role largely one of devout attention from the pews. The priest stood at the altar facing away from the people towards the back of the sanctuary, even for the readings, and had to say parts of the Mass inaudibly. The Mass as it was said in Britain in the 1950s had remained little changed since the Council of Trent, which had set down a version of the liturgy for near-uniform use across the Church in 1570. Slowly, however, the ‘dialogue Mass’ was introduced to Britain from Europe, involving congregational responses. In the new liturgy, developed in stages from the mid-1960s until 1970, the Mass was increasingly said in the local language and entirely so in its final phase. Then the priest would stand behind the altar facing the people; the congregation would join in with responses and singing, some giving readings from the sanctuary and forming an offertory procession; and the rites were radically simplified in texts and gestures. This shift in the forms of worship changed what the Church required from its buildings. The shape of the church and its congregation had to relate to the conception of the liturgy as a communal action; increased movement of both congregation and celebrants required new spatial forms; the sanctuary had to be designed afresh. Other rites were also reformed with further implications for the design of the church, most notably baptism.

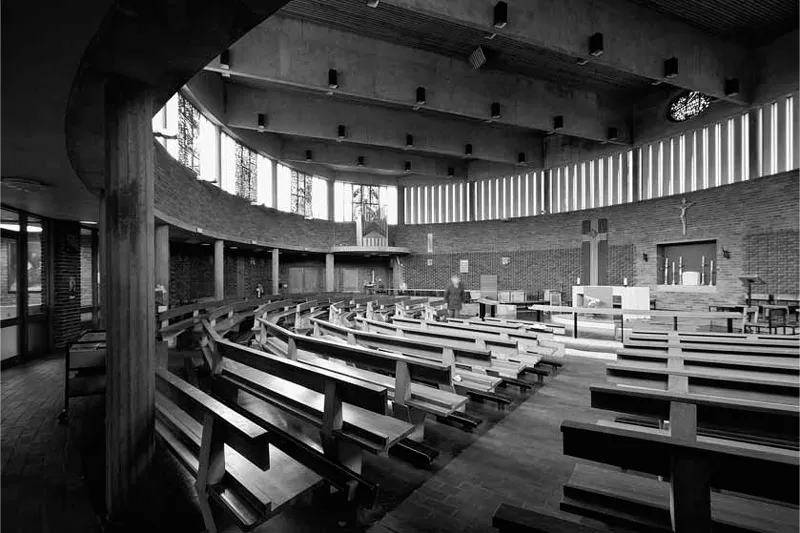

1.1 St Gregory, South Ruislip, London, by Gerard Goalen, 1965–67. View of nave looking towards sanctuary: sanctuary stained glass by Patrick Reyntiens, © Patrick Reyntiens, all rights reserved, DACS, London, 2013; clerestory stained glass by Charles Norris, added c.1987. Photo: Robert Proctor, 2010

In South Ruislip, Dayer and Goalen established their plans for the sanctuary layout in 1965 in direct response to the liturgical reforms emanating from the Vatican. The simple table-like stone altar was placed well forward in the oval sanctuary so that the priest could stand behind it to say Mass facing the people, and the tabernacle was placed in a broad niche on the wall behind it, an arrangement that served the new forms and conceptions of the liturgy just then enshrined at the council (Figure 1.1). Cardinal Heenan approved the plans himself shortly before setting out for Rome to attend the final session of the council.15 The Church’s reforms of liturgy and its approval of new theology thus had immediate effects on church architecture even in this suburban parish.

CHURCH AND ARCHITECT

Roman Catholic church buildings were also produced by their architects, and most were also members of the Church. At the time of his design for the church at South Ruislip, the architect Gerard Goalen gave his own talk to the parishioners. He began with a discussion of the Second Vatican Council, its ‘Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy’ of 1963, and the liturgical movement, the combined theological and architectural developments that led to the co...