![]()

Section VI

International trade: to West, South, East, and North

![]() West and North

West and North![]()

20. Byzantine trade to the edge of the world: Mediterranean pottery imports to Atlantic Britain in the 6th century

Ewan Campbell and Christopher Bowles

The imported Mediterranean pottery found in western Britain and Ireland has been the subject of debate since its first identification in 1956 by Ralegh Radford, based on his excavations at Tintagel, Cornwall. The explanations for its presence have varied from the religious, through economic to diplomatic. This paper will analyze the imports in the light of recent advances in our understanding of Mediterranean trading-patterns, and is based on a detailed survey of the Insular material.1 Although Mediterranean amphorae were imported into 4th-century Roman Britain in small quantities, these are always found in urban contexts in southern and eastern Britain, and apparently reached Britain by the Rhine/Rhone route. In contrast, the late 5th-/6th-century Mediterranean imports occur on an entirely separate set of sites, mainly coastal, in Atlantic Britain and in Ireland.

Britain at this period lay at the fringes of the Byzantine conceptual world, an island in the abyssal Ocean that was believed to encircle all known land. For example, Jerome’s commentaries on Isaiah and Amos refer to the Oceanus Britannicus as the extremity of the earth in the West, and early Christian monks such as Adomnán of Iona considered themselves to be as far from the centre of the world (Jerusalem) as it was possible to be.2 By what processes did Byzantine amphorae and tablewares reach such an apparently isolated region? Admittedly, other Byzantine products reached as far as China, but these tend to be high-quality glass or metalwares, possibly sent as diplomatic gifts. In other cases where Mediterranean amphorae were traded long distances outside the Mediterranean basin – for example, to southern India and eastern Africa –, they are associated with a return trade in rare raw materials such as gems, precious metals, spices and ivory. In these cases, trade-related items such as weights, scales and coins are often found along with the pottery.3 Whether or not the British material is the residue of similar trading-practices has to be assessed solely from an archaeological analysis of the Insular occurrences, as there are no credible contemporary historical sources on the subject.

The Mediterranean Package of Wares

The Insular occurrences of Mediterranean imports fall into two sub-groups: an earlier one with a provenance in the north-eastern Mediterranean, and a later one with a provenance in the Carthage region of North Africa. However, there are good grounds for considering these to be part of one trading-system, and they will be discussed together here.

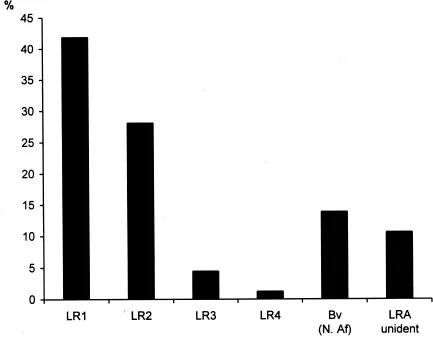

Four types of post-Roman pottery found in Atlantic Britain are now known to have been manufactured in the Aegean or the north-eastern Mediterranean region: Phocaean Red Slip Ware (PRS) tableware, and LR1, LR2 and LR3 amphorae. These four identified wares make up 71 per cent of all the Atlantic Mediterranean imports, with the North African wares forming only 19 per cent (fig. 20.1). In the western Mediterranean, these wares are also often found in association with each other, but also with wares from the south-eastern Mediterranean, namely LR4–LR7 amphorae, which are almost entirely missing from Atlantic sites. Dating of the finewares accompanying the amphorae shows that the northeastern Mediterranean package was imported during the period c. 475–525, and was supplemented, or more probably replaced, by a package of wares from Tunisia for a short period around 525–50. This new package contained African Red Slipware (ARS) tableware and North African cylindrical amphorae.4

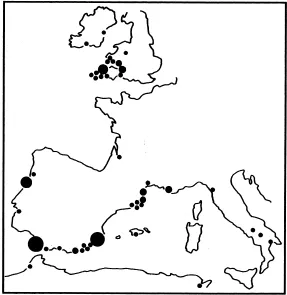

The lack of Gaza and Palestinian amphorae is only one of a number of differences between the western Mediterranean and the Atlantic import assemblages. LR2 is normally rare in the western Mediterranean, accounting for a maximum of 7 per cent of amphorae at any site, but it forms 37 per cent of the identified amphorae on Atlantic sites. The low proportion of ARS (32 vessels) to PRS (62 vessels) is also striking, and very different from the normal situation in the western Mediterranean, where ARS dominates. The lack of Cypriot Red Slipware (LRD) is another important difference, as this is often found alongside PRS on western Mediterranean sites.5 The actual quantities of PRS found on 17 sites in Britain, measured by minimum number of vessels, are comparable to those on sites in Spain, despite their being much further from the source area (fig. 20.2). The most recent summary shows 26 PRS sites in the western Mediterranean, mostly producing a few vessels each, with only three sites (Coimbriga, Benalúa and Belo) reaching double figures.6 These three sites lie on southern coasts, on the sea-route to Britain. Finally, the date-range of the Atlantic imports is more restricted than in the western Mediterranean, where LR1 ranges from c. 425–600, and LR2/PRS from c. 450–600.7 These five factors immediately show that there is something peculiar about the Atlantic trading-system, and that explanations for its existence must differ from those used to account for the western Mediterranean distribution, which can be explained by normal commercial activities involving the transport of staple commodities such as wine, oil and grain.

The characteristics of the north-eastern Mediterranean package show that it results from direct contact with Byzantium, not mediated through any western Mediterranean sites, except for a late phase originating in the Carthage region.8 They also show that the trade lasted for a considerable period, at least seventy-five years, and stopped prematurely around 550. These factors have a strong bearing on recent attempts to link the trade with a Byzantine diplomatic initiative associated with Justinian’s attempted reconquest of the western Mediterranean.9

Figure 20.1 Relative abundance of Mediterranean amphorae in Insular contexts (MNV).

Figure 20.2 Comparison of numbers of Phocaean Red Slip Ware vessels in western Mediterranean and Britain (symbol size proportional to number of vessels).

Patterns of Consumption

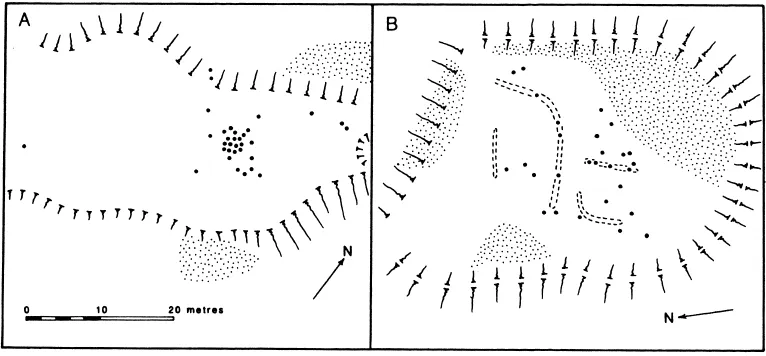

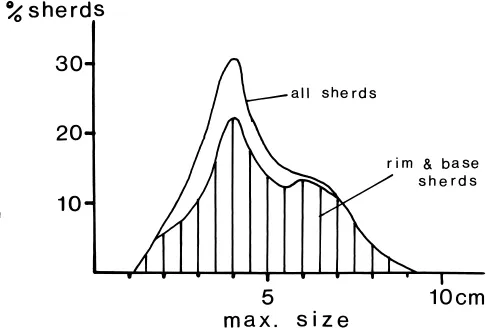

Detailed studies of the Mediterranean pottery on British sites, using modern taphonomic techniques, have revealed details of how the pottery was used in early medieval society. For example, detailed distribution patterns of sherds from individual vessels, combined with sherd size analysis, have shown that a putative timber hall at Cadbury Castle, Somerset, identified within a mass of post-holes, was indeed associated with the Mediterranean package of wares and therefore occupied in the 6th century.10 At Longbury Bank, Dyfed, a similar analysis using the concept of artefact traps helped to identify activity areas and confirm the presence of a fugitive building, all trace of which had been removed by ploughing (fig. 20.3).11 At Tintagel, sherd size analysis showed that workmen in the 1930s excavation had selectively kept only rim- and decorated sherds from the red slipwares (fig. 20.4).

At the inter-site level, distribution studies show that the types of sites where concentrations of imports are found differ from those in Mediterranean and other parts of north-western Europe. Sites such as Tintagel, Dinas Powys or Cadbury Castle are all hilltop fortified elite residencies rather than coastal trading-stations or towns. Several of the sites have documented royal associations or evidence of activities associated with royalty.12 Bantham in Devon is an exception in that it appears to be an undefended beach market. The direct use of imported wine and oil at the residencies of the elite illustrate the value placed on these commodities by the communities receiving them, and it has been argued that they were used by royalty to re-enforce a hierarchical society through gift exchange and control of access to foreign luxuries. This direct use of trade goods contrasts with the situation in Anglo-Saxon and continental Europe, where kings kept trade at arm’s length.13 The rulers of these forts controlled areas only a few tens of kilometres in extent, though they often styled themselves as kings. This situation has implications for explanations about the function of the imports.

Figure 20.3 Distribution of imported glass at Longbury Bank, Dyfed (A), compared to structure at Dinas Powys, Glamorgan (B), showing ‘ghost’ building identified by micro refuse patterns.

Figure 20.4 Tintagel sherd size curves for Mediterranean Red Slip Wares from 1930s excavations, showing selective retention of only rim and base sherds.

Cargoes and Trade

The debates that the Mediterranean imports raise have revolved around the mechanisms of delivery (routes, ships, merchants), the size and nature of the cargoes, and the motives for its inception. As already mentioned, the direct sea-route from a starting-point somewhere between Antioch and Constantinople, via the Straits of Gibraltar, is now accepted by most commentators. The detailed composition of the Atlantic assemblages, and in particular the lack of various eastern wares such as lamp Bailey Q3339 and Aegean Fulford casserole 35, along with the low quantity of ARS, shows direct contact with Britain, not stopping at Carthage or southern Spain.14 Recently, it has been suggested that the Byzantine vessels may have offloaded their cargoes in Portugal, and that local vessels more suited to the rigours of Atlantic travel continued the voyages to south-western Britain.15 One argument in favour of this ‘two-stage’ voyage is the lack of evidence for Byzantine shipwrecks in Atlantic Britain despite intensive diving exploration in these waters. This argument is suspect, however, as it is equally true that only one possible Roman wreck has been found in Atlantic waters, and that probably of 1st-/2nd-century BC date, despite the huge volume of Roman ship movements that must have taken place in these waters in the four centuries of Roman occupation.16 It is also difficult to see why such offloaded cargoes would be taken on to Britain, rather than distributed in Portugal. It is, however, possible that cargoes could have been offloaded at the Isles of Scilly, or alternatively, local pilots taken on board there. There are indications that Scilly did function as a merchant’s stopover point in the later 6th and 7th centuries.17 It is certainly true that the restricted harbour at Tintagel Haven would be difficult for a foreigner to find and negotiate safely without local support.

This discussion has raised the question of the size and type of vessels likely to have made these vo...