- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Structural and Civil Engineering Design

About this book

The importance of design has often been neglected in studies considering the history of structural and civil engineering. Yet design is a key aspect of all building and engineering work. This volume brings together a range of articles which focus on the role of design in engineering. It opens by considering the principles of design, then deals with the application of these to particular subjects including bridges, canals, dams and buildings (from Gothic cathedrals to Victorian mills) constructed using masonry, timber, cast and wrought iron.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The mechanization of design in the 16th century: the structural formulae of Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón

Sergio Luis Sanabria

The existing fragments of an architectural booklet by the 16th-century Spanish architect Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón reveal an ingenious attempt to systematize the design process by creating a sequence of formulaic procedures to be followed in ecclesiastical projects. The formulae are addressed to two more or less separate issues. The first is to synthesize Gothic and Classic proportioning methods, and demonstrate their fundamental identity. The second is to establish an independent "science" of structural design. Aside from the more theoretical writings of Leonardo da Vinci, the work of Rodrigo Gil is the principal evidence extant for the development of structural thinking among 16th-century master masons.

Seven formulae discussed here are concerned with the correct depth of a buttress to support an arch or a rib vault. The formulae do not seem to have been derived through theoretical analysis, using the medieval Scientia de Ponderibus. Rather they are the result of new experimentation and traditional Gothic geometric thinking applied to classical arches, and of new arithmetic procedures applied to Gothic rib vaults.

Introduction

ITALIAN ARCHITECTS of the 16th century developed the expressive range of classical vocabulary far beyond its tentative appearances in the 15th century. This dazzling artistic development has masked the contributions made to the building arts by Late Gothic architects, so that the entire range of progressive ideas of the 16th century often is ascribed mindlessly to the Renaissance movement. This is true of technical developments in structural analysis. The standard story, as told by W. B. Parsons, begins with the precocious but uninfluential work of Leonardo ca. 1500 on the bending of beams, the geometric resolution of force diagrams, and the analysis of arches. It then leaps ahead to the 17th century and Galileo's publication in 1638 of Dialoghi delle nuove scienze, with its still incorrect analysis of a cantilevered beam. The inventions of the triangulated truss, exemplified in the work of Vasari and Palladio, and of laminated beams by Philibert de L'Orme are treated as practical inventions of the second half of the 16th century, of limited theoretical importance.1

Even Robert Mark, a staunch admirer of Gothic structural achievements, views Late Gothic with its codification of design rules as having stifled structural experimentation.2 Certainly the peak of intuitive structural experimentation was reached earlier, with the construction of the great cathedrals of the Ile-de-France in the 13th century and of Catalonia in the 14th. At this time scholastics such as Jordanus Nemorarius (fl. 1220—1230), who rekindled the theoretical study of mechanics (scientia de ponderibus), were apparently unable or unwilling to make any contribution to the analysis of the vast and complex buildings then going up, often in the midst of the schools where they taught their Archimedean doctrines.3

Thus, according to a widespread viewpoint, the 15th and 16th centuries saw a decline in structural inventiveness, with no significant experimentation other than the introduction of some new forms, and no progress in theoretical analysis. I believe that this overly-negative evaluation of Late Gothic achievements is premature, due to insufficient studies. The writings of the Spanish architect Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón illuminate this obscure subject and show the transitional development of structural thinking in the 16th century, stimulated by Gothic tradition, humanist ideas, new mathematical tools, and an incipient experimental approach to theory.

Fig. 1. Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón. Choir of Cathedral of Astorga. Late 1530S-1559 (author).

Fig. 2. Rodrigo Gtl de Hontañón. Alcalá de Henares. Universidad Complurense, Colegio de San Ildefonso. ca. 1538 (source unknown).

Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón and his treatise

Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón (ca. 1500/1510—1577) was perhaps the most prolific and versatile Spanish architect of the 16th century.4 His career spans the last flowering of the Gothic and the simultaneous development of the Renaissance in Spain. As a Gothic master mason, the director of a thriving construction firm, Rodrigo Gil conducted the works at the Cathedral of Astorga from their inception in the 1530s to 1559 (Fig. 1). He was responsible from 1538 for the two largest cathedrals under construction in Spain, Salamanca and Segovia, both already begun under his father, Juan Gil de Hontañón. Rodrigo also inherited two major works by Juan de Alava, the cloister of the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in 1538, and the soaring Cathedral of Plasencia in 1544. These buildings rank Rodrigo as the most important Late Gothic master in Spain.

At the same time, Rodrigo was very aware of the new classical vocabulary spilling from Italy and was one of the foremost masters of the Plateresque Renaissance in Spain. The facade of the College of San Ildefonso at the University in Alcalá de Henares, begun about 1538, is perhaps his best known work, where he combines Late Gothic geometric proportioning methods with Renaissance forms (Fig. 2).

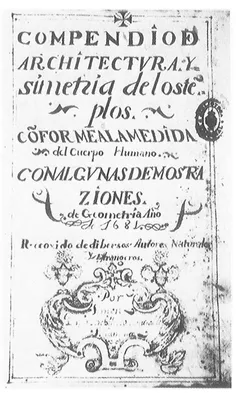

Despite an extremely busy and peripatetic career, Rodrigo found time to jot down notes for an unfinished treatise on architecture, attempting a synthesis of Classicism and Gothic. Although his original writings have not survived, parts of his text and illustrations, which apparendy were kept at the fábrica of the Cathedral of Salamanca, were copied before 1681 by Simón García, a Salmantine architect born ca. 1651, as part of a Baroque compendium on a variety of architectural subjects (Fig. 3). Simón García's Compendio de Arquitectura y Simetría de los Templos, now at the Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, MS. 8884, is a handwritten codex of 141 folio pages, with 77 chapters.5Chapters 1 through 6 are based mostly on the notes of Rodrigo. Chapter 75 plus an illustration at the end of Chapter 16 can also be attributed to him.6

Fig. 3, Simón García. Compendio de Arquitectura y Simetría de los Templos. Title page. 1681 (Biblioteca Nactonal de Madrid).

It is almost impossible to distinguish between the rough and unpolished writing styles of the two men, which suggests that Simón rewrote much of Rodrigo's text. The only clue is that Simon seems more prolix and prone to insert learned references in inappropriate settings. Some caution in attribution of ideas is therefore essential while reading Rodrigo's chapters.

Dating of the original manuscript of Rodrigo Gil can be based only on internal evidence. The earliest notes on human proportioning in the book must be dated after 1544, by a reference in Chapter 2, 2r, to Guillaume Philandrier's In Decem Libros Vitruvii de Architectura Annotations, published in Rome in 1544. In Chapter 6, 22r, there is a reference to what may be a personal discussion with Pedro Sańchez Ciruelo, Darocensis, polymathic professor of mathematics, theology, philosophy, logic, and musk at Paris, Alcalá and Salamanca, tutor of Philip II, who died in 1554. Thus much of Chapter 6 must date before this time.

In his booklet Rodrigo describes a nearly mechanical design process for church architecture guided by strictly predetermined routes, but with many free choices along the way.7 Although Rodrigo probably never employed this methodology in his own designs, the process interested him because it would have simplified the repetitive tasks of design in a large architectural firm. The first step is to determine the size of the church, and this is done with a formula using the parish population. The formula, inChapter 2, 3V, yields 28 square feet per inhabitant, based on the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- General Editor's Preface

- Introduction

- DESIGN RULES AND METHODS

- THEORETICAL JUSTIFICATION IN DESIGN

- PROGRESS IN ENGINEERING DESIGN

- Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Structural and Civil Engineering Design by William Addis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.