![]()

PART I

Creative and Sustainable Cities: Principles and Perspectives

![]()

Chapter 2

Creative Cities: Context and Perspectives

Tüzin Baycan

Cities as Creative Milieux

In today’s information economy, knowledge and creativity are increasingly recognized as key strategic assets and powerful engines driving economic growth. Cities have become the strategic sites, as they represent the ideal scale for the intensive, face-to-face interactions that generate the new ideas that power knowledge-based innovation (Bradford 2004a). While creativity constitutes a response to some of the economic challenges raised by globalization, paradoxically it requires initiative and organization at a local level (KEA 2006). Kalandides and Lange (2007) have called these ‘globalization paradox’ and ‘identity paradox’. ‘Globalization paradox’ addresses the ambivalence between local-based creativity and transnational networks of production systems, whereas ‘identity paradox’ addresses the ambivalence between individual or collective careers, identities and reputations. While creativity is an essential parameter in global competition, it is fostered and nurtured by exchanges of information and experiences at a local level (KEA 2006). The high concentrations of heterogeneous social groups with different cultural background and different ways of life have made cities incubators of culture and creativity (Baycan-Levent 2010, Merkel 2008, UNCTAD 2008). Besides knowledge and innovation, culture and creativity have become the new key resources in urban competitiveness. Cultural production in itself has become a major economic sector and a source for the competitive advantage of cities (Florida 2002, Merkel 2008, Miles and Paddison 2005, Musterd and Ostendorf 2004, Zukin 1995). Cultural and creative activities have shaped the competitive character of a city by enhancing both its innovative capacity and the quality of place, which is crucial to attracting creative people (Gertler 2004).

Knowledge, culture and creativity have also become the new keywords in the understanding of new urban transformations (Hall 2004). While cities are the key drivers of economic change, culture plays a crucial role in this process not just as a condition to attract the creative people but also as a major economic sector (Florida 2002, Miles and Paddison 2005, Musterd and Ostendorf 2004, Zukin 1995). The existing literature shows that cultural and creative industries are deeply embedded in urban economies (Foord 2008, Pratt 2008, Scott 2000). The role of cultural production in the new economy has radically changed the patterns of cultural consumption (Quinn 2005), and cities have transformed from functioning as ‘landscape of production’ to ‘landscape of consumption’ (Zukin 1998). The new patterns of cultural consumptions offer big opportunities for local and regional development (Marcus 2005).

In parallel to this transformation or ‘cultural turn’ a corresponding movement of ‘image production’ has emerged, especially in the advanced industrial societies (Quinn 2005). ‘Culture-led regeneration’ and ‘city marketing’ have become the main strategies of cities in order to create a ‘good image’ and attractive and high-quality places. As mentioned also by (Peck 2005) the creative economy is not only about creative people and creative industries but also about marketing, consumption and real-estate development. The new economy pushes cities to search for new spatial organization through urban restructuring (Sassen 2001) and in the restructuring process art and creativity play an important role as the key growth resources (Sharp et al. 2005). In order to create visual attractions and appealing consumption spaces urban renewal programmes consider waterfront revitalization, museum quarters, and so on (Merkel 2008).

Today over 60 cities worldwide call themselves ‘creative cities’, from London to Toronto and from Brisbane to Yokohama (UNCTAD 2008). Creative cities use their creative potential in various ways: some function as nodes for generating cultural experiences through the performing and visual arts (UNCTAD 2008); some use festivals that shape the identity of the whole city as part of their urban regeneration and city marketing strategies (Quinn 2005); and others look to broader cultural industries to provide employment and incomes.

Creative cities have also become a global movement reflecting a new planning paradigm in recent decades. The general features of creative cities are described by many scholars; however, as also mentioned by Bradford (2004a), the studies describe the conditions that foster creativity, and the mechanisms, processes and resources that turn ideas into innovations remain very limited. From the point of view of this need, this study aims to put the current debate about creative cities in context and perspective while addressing the most recent studies from a multidisciplinary perspective. The study offers a framework that is based on the 10 most frequently asked questions (FAQs). In other words, the study aims to highlight the ‘Top 10 FAQs’ in the creative cities debate. The next section begins by describing creativity and its dimensions, and is followed by a discussion of the key concepts in urban creativity in the third section. Then, the fourth section investigates the general features of creative cities and highlights the Top 10 FAQs in the creative cities debate. The last section considers the policy roadmap to the creative city and the challenges for government.

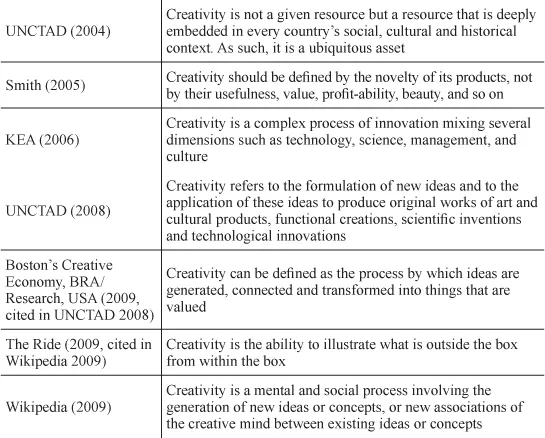

Creativity: Dimensions and Perspectives

Creativity has been studied by different disciplines such as psychology, psychometrics, cognitive science, artificial intelligence, philosophy, history, economics, design research, business and management, and from different perspectives including artistic, scientific, economic and technological. These studies have covered everyday creativity, exceptional creativity and artificial creativity. However, there is no single or simple definition of creativity (the notion has more than 60 definitions (Sternberg 1999) that includes all the different dimensions of this phenomenon). On the one hand, there have been inconsistencies concerning the definition of creativity and, on the other, creativity definitions overlap and interwine (Table 2.1). Similar to the existence of inconsistencies in the definition of creativity, there are also inconsistencies in the methodologies used to measure creativity. There is neither a standardization of methods or measurement techniques nor a systematic approach (Afolabi et al. 2006, Wikipedia 2009).

Table 2.1 Different definitions of creativity

As can be seen from Table 2.1, creativity is a complex phenomenon and associated with originality, imagination, inspiration, ingenuity and inventiveness. A unifying definition of creativity is challenging but also difficult as it has been argued by various researchers that creativity is domain specific (Afolabi et al. 2006). However, in order to find a unifying definition of creativity Rhodes (1961) did an extensive search and found that the definitions are not mutually exclusive. According to Rhodes (1961), creativity definitions form four strands: 4P (PERSON – identification of the characteristics of the creative person, PROCESS – the components of creativity, PRODUCT – the outcome of creativity and PRESS – the qualities of the environment that nurture creativity) and each strand has a unique identity. Torrance (1976) similarly observed that creativity has usually been defined in terms of process, product, personality and environment. He redefined creativity as ‘a successful step into the unknown, getting away from the main track, breaking out of the mold, being open to experience and permitting one thing to lead to another, recombining ideas or seeing new relationships among ideas’. Torrance’s definition of creativity has been widely accepted by many researchers.

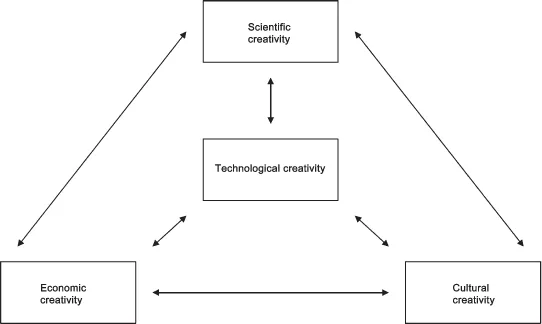

The characteristics of creativity in different areas have been suggested by UNCTAD (2008: 9) as ‘artistic creativity’, ‘scientific creativity’, ‘economic creativity’ and ‘technological creativity’:

• ‘artistic creativity’ involves imagination and a capacity to generate original ideas and novel ways of interpreting the world, expressed in text, sound and image;

• ‘scientific creativity’ involves curiosity and a willingness to experiment and make new connections in problem solving;

• ‘economic creativity’ is a dynamic process leading towards innovation in technology, business practices, marketing, etc., and is closely linked to gaining competitive advantages in the economy;

• all these characteristics of creativity in different areas are interrelated and involve ‘technological creativity’.

Therefore, ‘creativity’ is defined in a cross-sector and multidisciplinary way, mixing elements of ‘artistic creativity’, ‘economic creativity’ or ‘economic innovation’, ‘scientific creativity’ as well as ‘technological creativity’ or ‘technological innovation’ (Figure 2.1). Here creativity is considered as a process of interactions and spillover effects between different innovative processes (KEA 2006).

Figure 2.1 Characteristics of creativity

Source: KEA 2006: 42.

Creativity has various dimensions and attributes. In psychology and cognitive science, the concept refers to individual creativity and mental representations and processes underlying creative thought (Afolabi et al. 2006, Kaufman and Sternberg 2006, Sternberg 1999, Wikipedia 2009). However, there is no agreement whether creativity is an attribute of people or a process by which original ideas are generated. The psychological dimension of creativity includes the attributes such as ‘convergent’ and ‘divergent’ thinking, age and gender differences, and the role of education in creativity (Baer 1997, Fasko Jr 2001, Kaufman and Sternberg 2006, Reis 2002, Sternberg 1999). The formal starting point for the scientific study of creativity in psychology is generally considered to be the studies after the 1950s and in particular J.P. Guilford’s scientific approach to conceptualizing creativity and measuring it psychometrically (Afolabi et al. 2006, Sternberg 1999, Wikipedia 2009). Guilford (1967) performed important work in the field of creativity, drawing a distinction between ‘convergent’ and ‘divergent’ thinking. Convergent thinking involves aiming for a single, correct solution to a problem, whereas divergent thinking involves the creative generation of multiple answers to a set problem. Divergent thinking is sometimes used as a synonym for creativity in the psychology literature.

The cultural dimension of creativity includes creativity in diverse cultures and different modes of artistic expression. Creativity in general seems to be enhanced by cultural diversity and cultural diversity provides sources for creative expression. The relationship between diversity and creativity has been investigated by many scholars in different disciplines from socio-economic, cultural and psychological perspectives (see for a comprehensive evaluation Baycan-Levent 2010). In these studies, diversity has been analysed in terms of demographic attributes (age, sex, ethnicity) and cognitive (knowledge, skills, abilities) aspects in order to explain whether it has a positive or negative effect on performance, creativity and innovation (Bechtoldt et al. 2007, Herring 2009). Many studies of collective creativity (teams, organizations) find that diversity fosters creativity. The results of research on heterogeneity in groups suggest that diversity offers a great opportunity for organizations and an enormous challenge. More diverse groups have the potential to consider a greater range of perspectives and to generate more high-quality and innovative solutions than do less diverse groups. In brief, while diversity leads to contestation of different ideas, more creativity, and superior solutions to problems, in contrast, homogeneity may lead to greater group cohesion but less adaptability and innovation.

Creativity is seen from an economic perspective as an important element in the recombination of elements to produce new technologies and products and, consequently, economic growth. In the early twentieth century, Joseph Schumpeter (1950) introduced the economic theory of ‘creative destruction’ to describe the way in which old ways of doing things are endegenously destroyed and replaced by the new. Today, the economic dimension of creativity can be so called because the ‘creative economy’ is an evolving and a holistic concept dealing with complex interactions between culture, economics and technology (KEA 2006, UNCTAD 2008). The creative economy is based on creative assets potentially generating economic growth and development. These creative assets consider ‘creative class’, ‘creative industries/cultural industries’, ‘entrepreneurship and innovation’ and ‘cultural entrepreneurialism’ (Boschma and Fritsch 2007, Ellmeier 2003, Florida 2002, Hartley 2005, KEA 2006, Fleming and NORDEN 2007, Musterd et al. 2007, UNCTAD 2008, Wu 2005). Creativity is increasingly recognized by economists as a powerful engine driving economic growth. It contributes to entrepreneurship, fosters innovation, enhances productivity and promotes economic growth.

The physical-spatial dimension of creativity refers to ‘creative milieu/innovative milieu’, ‘creative city’ and ‘quality of place’ (Bradford 2004a and 2004b, Crane 2007, Drake 2003, Evans 2009, Florida 2002, Foord 2008, Hall 2000, Jones 2007, Landry 2000 and 2007, Musterd et al. 2007, UNCTAD 2008, Wu 2005, Yip 2007). Creativity is seen from an urban perspective as ‘a collective process emerging from a broader crerative field characterized by place-based clusters of cultural industries’ (Rantisi et al. 2006: 1790). In general, creative industries tend to cluster in large cities and regions that offer a variety of economic opportunities, a stimulating environment and amenities for different lifestyles. Creative industry development is often considered part of the inherent dynamic of urban spaces, and urban environments provide ideal conditions – a creative milieu – for cluster development (Landry 2000, Porter 1998, Porter and Stern 2001). Cities and regions around the world are trying to develop, facilitate or promote concentrations of creative, innovative and/or knowledge-intensive industries in order to become more competitive. These places are seeking new strategies to combine economic development with quality of place that will increase economic productivity and encourage growth.

Although the wealth of literature regarding the development of creativity indicates wide acceptance that creativity is desirable, it is not as highly rewarded in practice as it is supposed to be in theory (Kaufman and Sternberg 2006, McLaren 1999). ...