2.1 A review

In an attempt to classify the alternative technical meanings that have been attached to political risk over time, the following definitions can be identified: (1) political risk as non-economic risk (Ciarrapico, 1992; Mayer, 1985); (2) political risk as unwanted government interference with business operations (Eiteman & Stonehill, 1973; Aliber, 1975; Henisz & Zelner, 2010); (3) political risk as the probability of disruption of the operations of MNEs by political forces or events (Root, 1972; Brewers, 1981; Jodice, 1984; MIGA, 2010); (4) political risk as discontinuities in the business environment deriving from political change and which have the potential to affect the profits or the objectives of a firm (Robock, 1971; Thunell, 1977; Micallef, 1982); (5) political risk substantially equated to political instability and radical political change in the host country (Green, 1974; Thunell, 1977).5

The first definition is typical of an initial phase in which firms and banks began to address the problem of assessing risks that could not be classified as mere business risks or be evaluated by simply looking at the economic fundamentals of a country. The second definition is quite restrictive and, as noted by Kobrin (1979), has relevant normative implications because it assumes that government intervention is necessarily harmful – in other words, that host government restrictions on FDI involve economic inefficiency. This is not always true, and in PRA the objectives of companies and host governments – which may diverge as well as coincide – should be analyzed accordingly, in order not to be misled by preconception. It could be added that, in light of the debacle of the ‘Washington consensus’, and also considering the financial and economic crisis beginning in 2008 – which exposed the implicit risks in the under-regulation of markets – the concept of laissez-faire government has lost much of its appeal to business theory and practice.

The third definition is perhaps the most precise from the semantic point of view, because it rightly considers political risk not simply in terms of events but rather in terms of the likelihood of events (harmful to an MNE’s operations). If the aspect of probability calculation is overlooked, by conceptualizing political risk in terms of mere ‘events’ which can have an impact on a firm,6 one might end up behaving like the proverbial fool who, when a finger is being pointed at the moon, only looks at the finger. Political risk calculation is an intrinsically forward-looking task (on this point, see Chapter 2), and political risk may well be structurally high, and be perceived as such by a firm, even in the current absence of possibly harmful events.

The fourth category of definitions is broader, since it focuses on the business environment rather than on the individual firm. The influential definition provided by Robock (1971) deserves a closer look:

Political risk in international business exists (1) when discontinuities occur in the business environment, (2) when they are difficult to anticipate, (3) when they result from political change. To constitute a risk these changes in the business environment must have a potential for significantly affecting the profit or other goals of a particular enterprise

(p. 7)

The idea of an existing, observable discontinuity in the business environment is quite common in definitions of political risk. Once again, it is important to underscore a point: even situations which apparently look stable – and that have been so for a relatively long time – may in fact be extremely risky. The notion of latent variables in statistics effectively illustrates this concept.7 Risk can be thought of as the likelihood of a certain event taking place. What is subsequently observed is, in fact, a binary outcome: either the event does take place or it does not. The idea behind latent variables is that they are generated by an underlying propensity for a particular event (say, a general strike, a revolution or a mere act of expropriation) to occur. The political scenario in a country may look stable because it actually is stable, or, paradoxically, it can look stable in a given moment notwithstanding the fact that the political regime in force is about to collapse. A quite effective example thereof can be provided by recalling that, on December 31, 1977, President Carter famously toasted the Shah of Iran for representing “an island of stability in one of the more troubled areas of the world” (Carter, 1977). In the wake of the subsequent and unforeseen Iranian revolution and of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, however, PR analysts and scholars such as Brewers had to acknowledge the fact that “the past stability of an authoritarian regime should not be taken as a predictor of future stability” (Brewers, 1981, p. 8). This lesson has proved valid also for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) countries which experienced drastic political change in the form of revolution in early 2011 (on the Arab Spring as a PR case study, see Chapter 3).

Robock also introduced a distinction that is particularly salient to this inquiry – that is, the distinction between ‘macro’ political risk (when political changes are directed at all foreign enterprises) and ‘micro’ political risk (when changes are selectively directed toward specific fields of business activity). Evidently, micro political risk assessment should be performed at industry – or even at firm – level, while, as can be seen from the present analysis, when writing about political risk in general, most authors are referring to macro political risk.

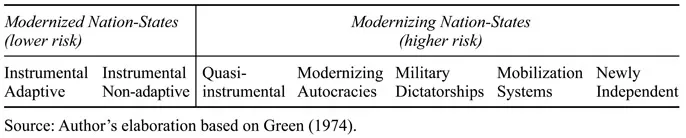

The fifth group of definitions was basically developed by authors who aimed to bridge the gap between political science and business studies, building on the extant scholarship on political change. Green’s contribution is the first to focus on the relationship between the type of political regime and political risk (Green, 1972, 1974). Seven types of regime are individuated, with an increasing level of risk (Table 1.1): Instrumental Adaptive (such as the US and UK) and Instrumental Non-adaptive (such as France and Italy), which are labeled as ‘modernized nation-states’; Quasi-instrumental (such as India and Turkey), Modernizing Autocracies (such as Syria and Jordan), Military Dictatorships (such as Burma and Libya), Mobilization Systems (such as China, Vietnam, Cuba and North Korea) and Newly Independent (such as Indonesia and Ghana), which are defined as ‘modernizing nation-states’. Green’s approach rests on a number of assumptions. The first is that radical political change is intrinsically detrimental to the activity of MNEs. The second is that the younger the political system, the less it is ‘adaptive’ to change, and thus the higher the risk of radical political change. The third is that economic modernization inevitably puts the political system under stress, and that political institutions in modernizing states must either change or be replaced. Although, as already pointed out, this analysis does focus on the origins of political risk in terms of political regime ‘structures’; it is not overly concerned with the empirical foundations of the claims made and does not delve into the specific mechanisms linking different kinds of political regime with political risk.

Table 1.1 Governmental forms and risk of radical political change

Today, more so than in the past, the task of political risk conceptualization and assessment is performed by private or public agencies (Business Environment Risk Intelligence, Control Risks, Eurasia Group, the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency in the World Bank Group, Oxford Analytica, Political Risk Services Group, to name but a few). As a matter of fact, most of them do not disclose – except to a very limited extent – their methodology for risk assessment, nor do they seem to agree on a precise definition of what a political risk is to the purposes of their activities. This aspect is particularly relevant because the lack of transparency in definitions and criteria for measurement is one of the reasons why the realm of political risk assessment is often hastily dismissed as a ‘soft’ science.

It is possible to draw some provisional conclusions from what has been said so far. First, despite several decades of scholarly endeavors, political risk in international business and political science seems to be affected by conceptual confusion. Second, in light of the renewed interest of scholars and practitioners of the subject, a reappraisal of political risk from the conceptual point of view seems timely. Third, no auth...