![]()

Chapter 1

‘All the Madmen’: Denouncing the Psychiatric Establishment and Supposedly ‘Sane’ Through the Art of Role Play

‘All the Madmen’ is the second track from The Man Who Sold the World,1 the album generally regarded as marking the beginning of David Bowie’s hard rock period.2 The song’s incorporation of role play, alongside its apparent veneration for the identified ‘mad’, make it a prime example of the way in which musical and verbal gestures can function to invoke an effective reversal of traditional concepts of madness and sanity.

Due to the quick succession of albums released, and Bowie’s previous interest in narrative forms, it is likely his audience throughout the early 1970s would have been accustomed to his use of characterization. As Allan Moore reveals: ‘Bowie forced attention upon the notion that a performer can inhabit a persona, rather than that persona being an aspect of the performer.’3 In the song ‘All the Madmen’ Bowie is playing the character of the labelled madman while still projecting the persona of the rock star. Our reading of Bowie’s character is thus shaped by our knowledge of his star status and vice versa; the distancing between them is what Frith refers to when he compares the act to that of a film star playing a role: ‘In one respect, then, a pop star is like a film star, taking on many parts but retaining an essential “personality” that is common to all of them and is the basis of their popular appeal.’4 While this observation regarding characterization may seem obvious, it has a greater relevance within this particular song for it enables a reading based on what has been termed the conspiratorial model of madness.

In The Myth of Mental Illness (1961), Szasz argues that what the majority of society and the psychiatric establishment refer to as mental illness is fundamentally separate and distinct from organic brain disease: ‘Strictly speaking, disease or illness can affect only the body; hence, there can be no mental illness. “Mental illness” is a metaphor. Minds can be “sick” only in the sense that jokes are “sick” or economies are “sick”.’5 In Szasz’s opinion, so-called ‘mental illness’ should therefore lose its mythical identity and be correctly defined as ‘personal, social, and ethical problems in living’.6 He offers a number of persuasive arguments in an attempt to elucidate the creation and perpetuation of this myth. The most crucial of these concerns the way in which mental illness serves as justification for the authority of the psychiatric profession while providing society with a means of labelling and hence scapegoating individuals whose behaviour is deemed undesirable:

Institutional Psychiatry is largely medical ceremony and magic. This explains why the labelling of persons – as mentally healthy or diseased – is so crucial a part of psychiatric practice. It constitutes the initial act of social validation and invalidation, pronounced by the high priest of modern, scientific religion, the psychiatrist; it justifies the expulsion of the sacrificial scapegoat, the mental patient, from the community.7

What is of particular relevance here is Szasz’s insistence that ‘mental illness is not something a person has, but is something he does or is’.8 In this sense once someone is, for whatever reason, labelled ‘mad’, they are, as a consequence, encouraged to take on the role of the insane person, as Szasz explains: ‘mental illness is an action not a legion. As Shakespeare showed […] it is also an act, in the sense of a theatrical impersonation.’9 Within my analysis of ‘All The Madmen’ one of my aims will therefore be to illustrate the ways in which Bowie’s characterization of madness represents Szasz’s myth of mental illness, for it exposes the myth for what it is – a role, a form of game play and a performance.

The theme emphasized initially in the song is that of alienation, or more specifically the alienation inherent within society itself. In the introduction and first two verses the listener is encouraged to feel empathy for Bowie’s character, who is left behind while his friends are taken away to ‘mansions cold and grey’. The imagery here draws upon eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century depictions of madhouses that were criticized for their inhumane methods of treatment and wrongful confinement. In her unfinished book The Wrongs Of Woman (1797) Mary Wollstonecraft’s protagonist, Maria, is incarcerated in a ‘mansion of despair’;10 Henry Mackenzie describes the living quarters of Bedlam in his classic The Man of Feeling (1771) in terms of ‘dismal mansions’;11 and John Conolly, a Victorian physician and head of Hanwell Asylum in Middlesex, told of the dreadful conditions prior to the licensing and inspection of asylums, referring to ‘gloomy mansions in which hands and feet were daily bound with straps or chains’.12 While the act of incarcerating people presumably against their will is called into question here, it is not, however, the source of Bowie’s character’s sadness. Rather, it is the isolation of the world in which he remains that proves undesirable.

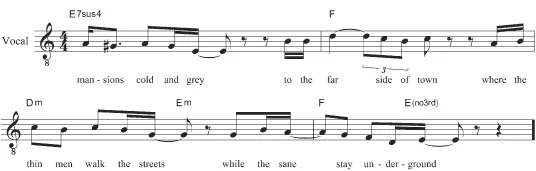

The sparse accompanying texture, comprising plectrum-strummed, steel-strung acoustic guitar and a lone synth call (which fades in and out a minor 6th above the tonic E), provides a suggestively bleak backdrop that is heightened by stark 4th and 5th intervals between two recorder sounds in verse two. The use of strummed acoustic guitar creates a sense of intimacy, being associated as it is with an accompanying role in songs with a more personal message, and this contrasts with the distancing of the vocal itself achieved through the use of panning and artificial reverb. The reverb seems excessive and effectively evokes the isolation of Bowie’s character, while the spatial dimension is significant in that the guitar shifts from far left to far right to make way for the voice entering alone, far left. This effect is further enhanced through the melodic line which, despite its use of an ascending major scale, appears confined and non-directed during the first two bars. Rhythmically dislocated, there are few obvious points of phrase repetition and the rhythms are sometimes clipped, sometimes lengthened to accentuate particular aspects of the lyric content (for example, ‘send’, ‘friend’, ‘mansions’ and ‘far’). The unhappy separation of Bowie’s character from his ‘friends’ is also emphasized through a leap up to the minor 7th and a 6–5 appoggiatura which stresses the word ‘far’ before descending back to its starting point via E Phrygian. The contour of the melodic line during the verse thus resembles a sigh; it grows in pitch and complexity, incorporating more non-harmony notes, before finally resolving back to the tonic (see Example 1.1).

The fact that the harmony resists change during the first three bars of the verse also offers little comfort, for the major identity is repeatedly challenged by the shift to E7sus4 in the beginning of bars two and three. The eventual move up a semitone to the F chord in bar four does offer some sense of release, but the progression to E Phrygian denies any reassurance of diatonic closure. The choice of Phrygian mode is in itself significant, having traditionally been used in western musical idioms to symbolize the unfamiliar with its characteristic minor 2nd interval carrying, according to Robert Walser, a ‘frAntic, claustrophobic effect’.13 While the tonic E remains a recognized point of stability during the verse, the harmonic language and modal melodic inflections are uncertain and this in turn represents the feelings of unease that surround Bowie’s character.

Example 1.1 ‘All the Madmen’ verse 1 (vocal and chords)

The sense of isolation and restlessness evoked in the opening musical and lyrical gestures is, I would argue, crucial to the overall message of the song. If Bowie’s protagonist is to convince us of his desire to stay with ‘all the madmen’, then we must have a point of comparison – his feelings in the opening represent the alternative, a life of loneliness among the supposed ‘sane’. While not an original concept, it does appear to reflect the thinking of R.D. Laing and his theory of man’s estranged state which he first articulated in The Politics of Experience (1967). Laing wrote: ‘The condition of alienation, of being asleep, of being unconscious, of being out of one’s mind, is the condition of the normal man’14 and he supported his belief by claiming that, for many people, their ‘true self’ is lost behind a ‘false self’ acquired to deal with a society that is profoundly estranged from reality.15 Such views had, in fact, become commonplace in the New Left’s attempts to highlight the necessity for social change, a change that would require involvement on a personal level to overcome what Theodore Roszak referred to as ‘the deadening of man’s sensitivity to man’.16 The suggestion that humanity’s ‘true self’ had been lost behind a mask adopted to succeed within a fake social reality was equally appealing to those who had chosen to ‘drop out’ of society – the Bohemian fringe of the counter-culture. Unsurprisingly, Laing became associated with the aforementioned groups and, indeed, similarities in his use of language are revealed if one compares arguments posed within The Politics of Experience with an extract from the SDS Port Huron Statement of 1962:17 ‘we regard man as infinitely precious and possessed of unfulfilled capacities for reason, freedom and love […] Loneliness, estrangement, isolation describe the vast distance between man and man today.’18 One can, of course, only postulate that such thinking had an impact on Bowie, although biographical writers such as Kate Lynch have pointed to his creation of a Bohemian lifestyle during his time at Haddon Hall (the setting for the original and controversial cover to The Man Who Sold the World)19 and his interest in Tibetan Buddhism (‘One must question one’s existence and when you do it leaves you with an incredible loneliness … Buddhism made me very keen on creativity’).20 Accompanied by statements in which he criticized ‘the whole idea of Western life’,21 these suggest a certain identification with contemporary radical opinion.

The notion that labelled madmen were, in fact, enlightened, honest, artistic individuals wrongly scapegoated by a sick society seems to have become more common during the late 1960s and early 1970s when through literature, film and music a number of artists set out to challenge conventional notions of ‘mad’ behaviour. In a similar affront to the Establishment, labels of insanity were used by certain theorists to criticize a society that continued to sanction acts of greed and war; and Michael Fleming’s research into portrayals of madness is valuable here, for he claims: ‘The production of such films [by which he is...