![]()

Chapter 1

Interpreting Temples: An Introduction

The broad religious and cultural interconnections between the classical temple architecture of Asia are well known and the architecture of the epic monuments, such as Khajurāho, Thanjavur, Prambanan and Angkor, are well understood. However, the precise connections and correlations between the earliest temple building traditions of India and its Southeast Asian counterparts remain unclear. This book attempts to fill this gap in our understanding of Early Brahmanic/Hindu Temple architecture through a broad comparative study of architectural archetypes and their adaptation across South and Southeast Asia.

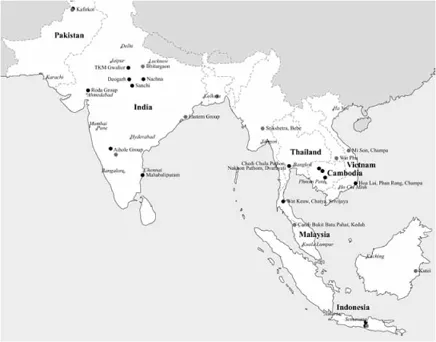

Across the breadth of South and Southeast Asia, from the Indus valley in northern Pakistan through the southeastern islands of Indonesia to coastal Vietnam, there are the remains of many earlier temples and monumental sites (see Figure 1.1). These sites present a complex but fragmented picture of the early interconnections between the temple building traditions of Asia that precede the famous monuments such as the Brihadeshvara Temple at Thanjavur, Angkor Wat at Angkor and Candi Loro Jonggrang at Prambanan. Small in scale, less spectacular in size and intent, and sometimes unknown except in specialist literature, these early sites provide significant clues to origins and architectonic connections.

The book presents the earliest examples of the Brahmanic/Hindu tradition of temple building in South and Southeast Asia. The book concentrates its scope on a basic archetypal architectural type, the Brahmanic/Hindu temple cella or garbhagrha. Tracing the basic cella from its origins and canonical formulations through to its physical adaptations across sites in India, Java and Cambodia, book provides a pan-Asian understanding of the early classical architecture, their connections and correlations, and evidence of the sophisticated linkages between the classic civilisations of Asia.

The Scope of this Book

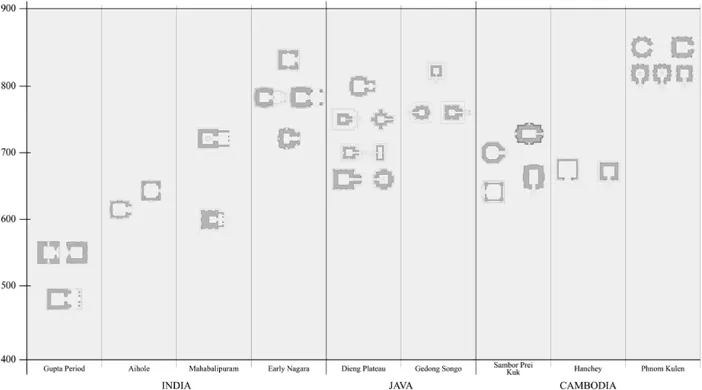

This book concentrates on the period 400 to 900 CE. Taking as its starting point the earliest substantial evidence of structural temple building in South and Southeast Asia (c. 400 CE), it traverses a spatio-temporal map (Figure 1.1) with its end point being the establishment of Angkor (c. 900 CE). The chronological spread and adaptation of this architecture shows that the Brahmanic/Hindu temples of South and Southeast Asia, while remarkably varied in their architectural expression form and composition, share a common typological origin rooted in the archetypal form of the early structural cella (Figure 1.2). In this archetypal schema, Southeast Asian temples, like other examples from the Brahmanic/Hindu tradition, can be considered as abstracted representations of Mount Meru.1 Their elements can be seen as corresponding with the three cosmic realms. The first is the podium or platform base, the second is the body of temple enclosing the sanctum and the third is the superstructure above.

Figure 1.1 Spatio-temporal map of early temples in South and Southeast Asia, 400–900 CE

It has not been possible to amend this figure for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472435002Fig1_1.pdf

Nevertheless, tracing the process of adaptation from canonical archetypal prescriptions to the material monuments is not straightforward. Regional variations of the earliest temples in Southeast Asia defy obvious or linear connections with those in the Indian subcontinent. However, the book establishes, through a comparative analysis of architectural typologies, the strong common roots of the corpus. Epigraphists, Sanskritists and historians have made significant historiographical connections between these traditions. This book offers a small step forward in establishing the specifically architectonic and compositional connections between the earliest monuments of South and Southeast Asia.

Figure 1.2 Chronological spread and adaptation of temple architecture across Asia

It has not been possible to amend this figure for suitable viewing on this device. For larger version please see: http://www.ashgate.com/pdf/ebooks/9781472435002Fig1_2.pdf

A Brief History of Temple Scholarship

The Study of Temple Architecture in South Asia

The first modern work of scholarship on temple architecture is attributed to Rām Rāz (1834). Rām Rāz’s posthumous essay attempts to establish the connections between canon and construction as summarised in the preface to his essay:

and, though it had long been known, proverbially, that the Hindús [sic] possessed treatises on architecture of a very ancient date, prescribing the rules by which these edifices were constructed, it remained for the author of this essay to overcome the many, almost insurmountable obstacles to the substantiation of the fact, and to the communication of it to the European world in a well known language of Europe.

The essay combines the knowledge of terminology described in Manasāra, a śilpa text in Sanskrit, with traditional śilpin knowledge of construction of the monuments themselves to understand its practice and references. This very first work establishes a rigorous basis for correspondence between text and practice, a methodological process that prevails throughout scholarship in the field. The complex triangulation between technical terms, description in treatises of architecture, actual practice and its evidence is realised through visual methods of representation. Fergusson (1845, 1864, 1876) laid the early foundation for the study of Indian architectural history through a direct recording of the buildings and their exposition through general principles of architectural theory, categories and styles. Fergusson’s History of Indian and Eastern Architecture remains the first standard text on Indian architecture. Fergusson is also credited with the introduction of the developing science of photography to record and explain monuments. Photographs, in his view, ‘had done more than anything that has been written’ (Chandra 1975: 3). Fergusson’s chronology and classification are further developed by Burgess (1888), Alexander Rea (1909) and Cousens (1931). As Rām Rāz had done a century earlier, Cousens attempted to incorporate technical terminology into his work and relate the extant monuments to the technical texts.

The 23 volumes of Archaeological Survey of India Reports (ASIR) are an indispensable guide to the survey and documentation of Indian architecture. Published under the direction of General Alexander Cunningham (1879, 1880, 1885), a large corpus of monuments of Indian architecture, including a large number of temples across Western and Central India, are covered in meticulous detail. In particular, Chandra (1975:10) notes his contributions to the chronology and outline of temples from the Gupta period. Manmohan Ganguli (1912) also exploited the methods of Rām Rāz, using knowledge from śilpa texts and traditional śilpis to shed light on the structure and proportion and construction methods.

Jouveau-Dubreuil (1917) provided a quantum leap in our understanding of temple architecture of the Pallavas by combining knowledge of actual monuments, living practices and systematic classification. In the latter, he extended the descriptive methodologies employed by his predecessors and introduced analytical methods based on comparison and systematic classification. While Jouveau-Dubreuil’s contributions were restricted to ornament and surface descriptions, disregarding other aspects of architectural analysis (Chandra 1975: 19–20), his analytical method, comparative analysis and systematic classification became firmly established in the literature of scholarship in the field.

Nirmal Kumar Bose’s Canons of Orissan Architecture (1932) combines knowledge of the surviving monuments with vernacular texts and traditional terminology from living architectural śilpi traditions. Acharya (1927, 1934) presented the first in-depth translation of Manasāra as well as the first encyclopaedia of classical architecture (1946). Kramrisch (1946) formulated the philosophical meaning and symbolism underlying the architecture of the Hindu temple. Her work remains the authoritative study, combining philosophical texts, śilpa-śāstras and architectural analysis. Coomaraswamy (1927, 1930) moved the study of the temple away from the material and functional dissections towards a more symbolic and abstract understanding of inner meanings underlying traditional architecture.

Seminal contemporary contributions have greatly expanded our understanding of the architecture of the Hindu temple. The work of Madhusudan Dhaky (1961, 1971, 1975a, 1975b) brings a renewed vigour to the study of temple architecture. In particular, the deployment of comparative and typological methods of analysis combined with literary descriptions of monuments and texts provides a scholarly elucidation of temple architecture. Meister (1974a, 1974b) expands the structural, formal and symbolic horizons to provide a total understanding of temple architecture. His method is based on a search for rigorous links between monument and text, and an understanding of exigencies of practice. Meister’s analytical method for the construction of temple plans (1976b, 1979b), his penetrating study of motifs (1981) and bold reconstructions (2006) bring morphological and semiotic approaches to the study of temple architecture. The documentation and classification of Indian temple architecture entered a new phase with the publication of the seven volumes of the Encyclopaedia of Indian Temple Architecture (Meister et al. 1983). Michell’s study of temple architecture (1989, 1995) and Tadgell’s substantial synthesis (1990) treat Hindu architecture in single-volume broad surveys of the architecture of the subcontinent. Hardy (2007a, 2007b) provides both an introduction to the subject and a sense of the whole, explaining the architectural design principles of the classical Nāgara and Drāviḍa (North and South Indian) ‘languages’ of Indian temple architecture, and connecting these with historical and religious contexts by showing common underlying patterns. Dagens (2009) provides a succinct and reasoned understanding of ‘the Indian temple’ in India and beyond; of its essential forms, rituals and symbols.

The Study of Temple Architecture in Southeast Asia

There is a long history of Southeast Asian temple scholarship. While pre-colonial records are scant, under the auspices of both Dutch and French colonial authorities, who respectively occupied the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and Indochina (now Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos), institutes were set up to study, document and sometimes preserve or restore ancient Southeast Asian sites, and theories about their origins and nature were developed. In Java, study of ancient temples and sites began in the eighteenth century, but only began systematically after the 1851 founding of the Koninklijk Instituut voor de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV)/Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies. This led to the beginnings of archaeological research, with the aim of preserving monuments such as Borobodur and Prambanan. Important early figures in this research were J.F.G. Brumund and N.W. Hoepermans, who compiled early inventories of monuments (Brumund 1868; Hoepermans 1913). Jans Laurens Andries Brandes produced studies on style, ornamentation and iconography in the early twentieth century (Brandes 1904, 1909), and in 1923 Nicholas John Krom, head of the Oudheidkundige Dienst (Archaeological Service), produced the first comprehensive account of ancient Javanese art and monuments with Inleiding tot de Hindoe-Javaansche kunst (Introduction to Hindu-Javanese Art). Archaeological studies of Javanese temples continued through the twentieth century, most notably with Ancient Indonesian Art by August Johan Bernet Kempers, who became head of the Oudheidkundige Dienst in 1947 (Bernet Kempers 1959), and F.D.K. Bosch’s Selected Studies in Indonesian Archaeology (Bosch 1961). By the time of these publications, Indonesia was an independent nation and the colonial institutes had been superseded by national bodies.2 Indonesian scholars then emerged, and the focus of temple research altered slightly to make connections between their ancient cultures and the new nation. Whereas previously Dutch researchers had concentrated on connections to Indian art traditions, L. Poerbatjaraka drew connections between Sailendras and Srivijaya (Poerbatjaraka 1958) and R. Soekmono concentrated on the specifically Javanese aspects of ancient sites (Soekmono 1995). A more architectural approach to Javanese temples was developing in the late twentieth century, mostly through the work of Jacques Dumarçay, a French architect who worked with Soekmono on the restoration of Borobodur. Apart from numerous articles in the Bulletin de l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient (BEFEO), Dumarçay’s The Temples of Java was the first concise account of ancient Javanese architecture (Dumarçay 1986b). More recently, interest in Javanese temple sites has shifted again, partially to a reassessment of Indian connections (Jordaan 1999a, 2006; Romain 2011) and partially to their cultural and social contexts (Haendel 2012). A recent study that has been most useful in combining extensive survey material with a discussion of contextual issues is Véronique Degroot’s Candi, Space and Landscape: A Study on the Distribution, Orientation and Spatial Organization of Central Javanese Temple Remains (Degroot 2009).

In Cambodia, the leading French colonial authority in the study of ancient monuments was L’École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO)/the French School of Asian Studies, founded in 1900 with its headquarters in Hanoi. The dominant figure in the early twentieth century was Henri Parmentier, who became head of the archaeological department of the EFEO in 1904, having already undertaken a study of the Cham monuments of southern Vietnam. Parmentier’s two-volume L’Art Khmèr Primitif remains the most comprehensive survey of Pre-Angkorian monuments, particularly as the ravages of war and the Khmer Rouge regime mean that recent researchers are often looking at buildings in a far worse state of deterioration than he encoutnered (Parmentier 1927). Jean Boisselier was another important figure. Curator of the museum in Phnom Penh from 1950, and the EFEO’s delegate in Cambodia from 1951, Boisselier directed much of the Angkor conservation work in the 1960s, and also compared Khmer and Cham art (Boisselier 1956). During this time Bernard Philippe Groslier conducted research across Cambodia and Champa and published widely, his Indochina being the most wide-ranging survey of the region’s art and architecture (Groslier 1966), though not the first to be readable in English.3 Conflict and the Khmer Rouge interregnum meant that from the 1970s to the 1990s there was little research in Cambodia, but since then there have been numerous studies. Much, of course, has concentrated on Angkor but the broad sweep of Khmer architecture has been summarised variously by Jacques Dumarçay and Pascal Royère with their Cambodian Architecture: Eighth to Thirteenth Centuries (Dumarçay and Royère 2001) and David Snellgrove with his Angkor Before and After: A Cultural History of the Khmers (Snellgrove 2004). More recently, Claude Jacques (former Professor of Archaeology in Phnom Penh’s Faculty of Letters) and Pierre Lafond have written The Khmer Empire: Cities and Sanctuaries from the 5th to the 13th Century (Jacques and Lafond 2007).

On a more specialised level, the work of the EFEO continues in Cambodia with the recent work of Christophe Pottier (2007), as does that of the more recently established Center for Khmer Studies, where Pinna Indorf’s Analysis of Form Composition in Early Khmer Architecture (ACEFKA): Field Notes and Observations has been provided invaluable techniques for understanding the architecture of Khmer temples (Indorf 2006). Jean-Baptiste Chevance’s comprehensive survey of Phnom Kulen’s temples, L’Architecture et le décor des temples du Phnom Kulen, Cambodge (Chevance 2005) and the work of Ichita Shimoda and the Sambor Prei Kuk Conservation Project in their investigations of Sambor Prei Kuk/Isanapura (Shimoda and Nakagawa 2008; Shimoda 2007) have also been most helpful in collating earlier researches with current research.

As Champa was also part of French Indochina, French researchers also dominated the field of Cham studies for much of the twentieth century. Parmentier again is the major figure here, responsible for the first inventory of Cham monuments, meticulous (if occasionally speculative) drawings and theories about their relationships with neighbouring cultures (Parmentier 1904). His studies still provide the basis of more recent overviews, such as J.C. Sharma’s Hindu Temples in Vietnam (Sharma 1997), though much research on Cham culture and antiquities has been developed at the Da Nang Museum of Cham Sculpture (DMCS), originally founded in 1919 with assistance from Parmentier. The museum’s catalogue, written by Emmanuel Guillon, is also a most lucid account of Cham art and architecture (Guillon 2001). In recent years, Vietnamese scholars have continued researches into Cham sites and writing about their architecture (Ngô 2006; Phuong 2008). Early sites in Myanmar (Sriksetra), Thailand...