![]()

Part I

Spatial cultures in the ancient and medieval worlds

![]()

1Ancient Rome

Mobility in Europe’s first metropolis

Ray Laurence

Introduction

Ancient Rome has been largely omitted from recent work on mobility in geography and the social sciences (e.g. Urry 2007). Rome as a growing metropolis from 300 BCE became a location for the development of new forms of mobility that developed in response to the size and continuing growth of the city. Urban journeys of several miles could be taken without seeing the countryside – so different from the urban–rural experience found for example in Pompeii, where within twenty minutes you could cross the city. Rome is one of the first documented cities that was detached from nature. Walking on Rome’s paved streets shifted the urban experience towards ‘clean’ streets and the avoidance of dirt associated with nature. This chapter seeks to engage the study of mobility in the city of Rome with some recent developments in the study of space and movement.1

Rome and conceptions of space

Mobility is a human practice that is culturally specific and, when we focus on ancient Rome we are examining mobility in a large preindustrial metropolis. Understanding mobility in its historical context involves engaging with theories of society and space, using the theory to recognise how Rome produced new concepts of space, new technologies of mobility, new urban spaces, a new language of space, new critical genres of urban discourse, new ideas on the nature of walking, new systems of traffic flow, and a gradation of space (from an angiportus or alleyway to a locus celeberrimus or famous place). Thus, David Harvey’s (2006) definition of space as a keyword provides a basis for considering how ancient Rome might be conceived within the systemic mode of thought at the heart of the Lefebvrian spatial turn: ‘material space’, that is experienced representations of space, such as maps, and spaces of representation, that refer to the psychological or mentalité of space. Lefebvre’s triad can be used in conjunction with Harvey’s own tripartite scheme: absolute space, relative space and relational space to create a conceptual grid that has implications for understanding our sources on the city of Rome (cf. Table 1.1; see also Laurence 1997).

Table 1.1‘Space’ as a keyword

| Material space

(experienced space) | Representations of space

(conceptualised space) | Spaces of representation

(lived space) |

| Absolute space | Walls, bridges, doors, streets, buildings, cities, mountains, etc. | Cadastral maps, landscape description | Feelings of contentment at home, empowerment |

Relative space

(time) | Circulation and flows of water, people, information, etc. | Antonine Itineraries

Exchange value = value in motion | Anxiety of congestion, exhilaration of time-space compression |

Relational space

(time) | Social relations, rental, odours, pollution | Surrealism = 2nd/3rd style wall painting | Visions, memories, dreams, stories, etc. |

We would place our textual evidence for movement in the category of relative space. These are all textual creations with complex literary and linguistic structures to them, that have a linkage to the material through the deployment of strategies of subjective realism- causing readers to feel that the fictional text might correspond to a lived experience. The material evidence from Rome has major limitations when compared to Pompeii, a site that has become a laboratory for the study of urban space over the last two decades (e.g. Poehler 2006). Moving across the category of relative space in Table 1.1, evidence for the exchange value of movement can be located in the measurement of distance by milestones and within a mentality of space-time that relates journey time to distance (for example, in Martial’s Epigrams or in the Antonine Itineraries, cf. Laurence 2011). The dependency on evidence from literary texts for movement, of, say, itinerant traders, causes our sources to be categorised in the Lefebvrian sense as either representations of space or spaces of representation. Actual practice eludes us, however much historians and archaeologists may attempt to reconstruct ‘daily life’ from these texts. Thus, we can only ever expect to have a history of the conception of mobility, as opposed to a history of mobility as a lived experience. We can say though, that the conception of mobility was spatially varied across the city of Rome, according to whether you viewed the city from a litter or sedan chair carried on the shoulders of others, or made your own way through crowded streets.

Table 1.2Principal foci of the spatial turn

| Dimension of socio-spatial relations | Principle of structuration | Observable patterns |

| Territory | Borders, boundaries, parcels, enclosure | Inside/outside (e.g. pomerium) |

| Place | Proximity, areal differentiation, area | Core to periphery (forum to angiportus) |

| Scale | Hierarchy | Dominant to marginal

(elite to plebs sordida) |

| Networks | Interconnectivity | Nodal points and their connections |

The relationship between space and society has become a major area of debate in social theory as each reformulation of the spatial turn attempts to add another dimension. The original focus on territory was followed by a greater interest in place which was then supplanted by new foci; first on scale and then on networks (see Table 1.2). Each refocusing of the spatial turn privileged one aspect of space–society relations while causing the others to be neglected. Theoretical developments emanating from the core disciplines of the spatial turn (principally geography) gradually found their way into archaeological thinking, which has witnessed equivalent shifts in emphasis from territory, to place, to scale and networks.

Table 1.3Integrating approaches to space and society

| Structuring principle | Field of operation |

| Territory | Place | Scale | Networks |

| Territory | Past and present

Emerging frontiers, borders, boundaries | Places in territory | Multilevel government | Interstate system |

| Place | Core-periphery, borderlands, empires | Locales, cities, localities, globalities | Differentiation of empowerment | Local/urban governance partnerships |

| Scale | Division of political power within the state | Scale as area rather than level | Vertical ontology of nested or tangled hierarchies | Parallel power networks |

| Networks | Origin-edge

Ripple effects | Global city networks, polynucleated cities | Flat ontology with multiple entry points | Networks of networks, spaces of flows |

Recently, Jessop et al. (2008) have developed a toolkit to cross-reference all four foci, so that the distinctive contribution of each approach is embedded within the context of the other three approaches (see Table 1.3). This integrated approach is of use not just in the study of contemporary cities, but also in the exploration of historical forms of urbanism. It is a system that can be readily adapted to the study of ancient Rome and the work of historians and archaeologists and integrated with the new toolkit of Jessop et al. (see Table 1.4).

Table 1.4Application of the intersection of territory, place, scale and networks to ancient Rome

| Structuring principle | |

| Territory | Place | Scale | Networks |

| Territory | Relational content to the past – static continuities | Relational content in the present | City prefect

Neighbourhood Magistrate | Metropolis to empire (Urbis–Orbis relationship) |

| Place | Edge of the city, extension of the city | Constitution of place through monumentality | Alleyway to famous place | Locale to emperor |

| Scale | Fragmentation of Rome into regions and neighbourhoods | Competing famous places

Decentring of place | Neighbourhood to forum | Paved streets

Regions |

| Networks | Relationship between neighbourhood and emperor | Creates many competing famous places | Communication forum to crossroad | Movement of knowledge and rumour |

Territory and space: four regions and, then, fourteen regions

The size of Rome meant it was an entity difficult to measure or conceptualise except via breaking it down into constituent territories (Haselberger 2007, 18–23, 224–237). There appears to have been a register or even a census of the people from the time of Julius Caesar based on the vici (neighbourhoods) and information derived from the owners of the blocks of apartments (insulae). The area within the republican walled circuit of Rome had been divided into four regions by Servius Tullius: the Subura (NB nothing to do with suburbs), the Esquiline, the Hills (Collina) and the Palatine. Yet, there was a hierarchy of tribes, Palatine being the highest, the Hills (Collina) the second, with the Subura and the Esquiline being distinctly inferior (Taylor 1952–4, 229). In 7 BCE this system was replaced by fourteen regions, including the fourteenth across the Tiber (Favro 1996, 135–140). These new regions were disconnected from the voting units and would seem to have been a system for enumerating the city, but also were a means to allocate resources to the city – for example, a cohort of vigiles (firefighters) was assigned to every two regions of the city (Nicolet 1991, 194–198). Each person was located by the census in a region and within a neighbourhood of that region. The territorial relationship, for the inhabitant, was mediated through neighbourhood magistrates and was focused on the altar(s) of the local gods known as the Lares Augusti. The territorial division of Rome created knowledge of the city, as much as administrative function, and it was with the measurement of the population of the city and its division into neighbourhoods that gave the emperor the power to ‘control’ Rome.

Place-territory interfaces – seven hills and the expanding city

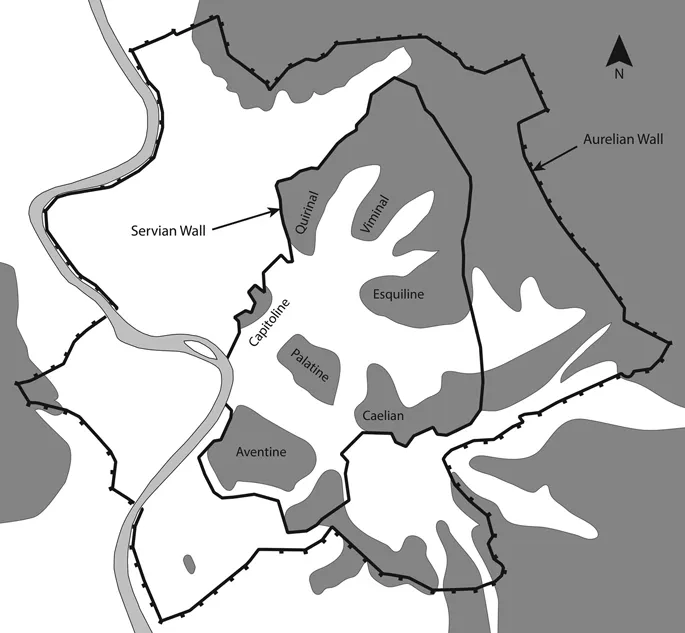

There are, however, other competing territorial divisions in Rome. A conception of the city as comprised of seven hills (Aventine, Caelian, Capitoline, Esquiline, Palatine, Quirinal and Viminal) that were a real and imagined territorial definition of Rome focused on those hills bounded by the Servian Wall (Figure 1.1).

The hills as raised ground create a sense of territory, but also can be named and thus become places in the city. Whilst at the same time, the phrase ‘seven hills’ can substitute as a metaphor to signify the whole city. There is a link between hills, walls and territory in the definition of Rome that can also be found in the establishment of Roma Quadrata defined by a wall around the Palatine Hill. Interestingly, the city extension under Servius Tullius, re-told by Livy, involved a growth in population and inhabited area that was to be defined by a wall and/or sacred boundary – the pomerium (Vout 2012, 77).

Intriguingly, these accounts from the end of the first century BCE imagine an expanding Rome from earlier times in which the city defied definition or required definition as comprised of fourteen regions – an increase not just from the four regions of the republic, but also a doubling of seven hills defining the city to fourteen regions. The principle of division is by seven: a magic number associated with seven celestial bodies known to the ancients. Just as the seven hills could be used to denote the whole of Rome, so could the fourteen regions. More importantly, there is a sense in which the regions that were at the edge of the built-up area of Rome could expand and become bigger, whereas the seven hills developed a canonical or fixed territorial short-hand for the city of Rome.2 The city as an expanding space was in many ways legally undefinable, causing the jurists to define the territory of the city by the term continentia (see Frézouls 1987 for discussion of definition of Rome’s territory) or as an agglomeration.

The great fire of Rome in 64 CE is an example of how the city’s territory included both the enumeration of space by the hills and by the regions. Tacitus measures the destruction with reference to the fourteen regions: four remained intact; three were levelled to the ground and in the other seven nothing survived but half-burned relics of houses.3 The linkage between regions and fire prevention in the distribution of the seven cohorts of fire brigade (vigiles) causes Tacitus’ linkage of regions to destruction by fire to invert the order of the city into disorder under Nero (Sablayrolles 1996, 245–289). The spread of the fire though was written with reference to the hills: it begins in the Circus abutting the Palatine and the Caelian and is stopped at the foot of the Esquiline six days later. The regions measured the territory of the city (and by implication the inhabitants in their homes), whereas the hills provided a definition of ...