![]()

PART I

A Biographical Study

Laistrygones, Cyclops,

the wild Poseidon – you will not encounter them,

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

(Konstantinos Kavafis, Ithaca)

![]()

Chapter 1

The Early Years in Greece (1904–1921)

‘But are there such violinists in Greece?’1

Following its recognition as an independent state in 1830 (after almost 400 years of Ottoman rule), mainland Greece was greatly afflicted by political upheavals and wars in the Balkans and Asia Minor in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This political, economic and social instability, whereby the last traces of feudalism gave way to an emerging middle class, coupled with religious objections towards musical innovation, delayed the growth of an indigenous art music. The Ionian islands, which were never under Ottoman domination, had enjoyed a rich musical life as a result of cultural contact with Italy.2 In contrast, Western art music was almost unknown in continental Greece until the end of Ottoman rule. Only in 1834 was modern European music, played by a Bavarian band imported by Greece’s first king, Otto, heard in the new capital, Athens (Leotsakos, 2001, 350). Gradually, mainland Greeks became exposed to polyphonically structured Western art music through such touring bands, which gave concerts in Athens and other provincial towns, performing popular dances and excerpts from symphonies by Beethoven, Mozart and Rossini. Their impact was profound, and by the end of the nineteenth century most Greek cities had their own municipal band, called Philharmonikes, which in turn generated a need for music schools (Trotter, 1995, 20). Nevertheless, art music in mainland Greece appealed only to a small minority of the upper classes, and serious students tended to emigrate to Italy, France or Germany for their musical training.

Formal musical education essentially started with the foundation in 1871 of the Athens Conservatory. Following two decades of parochial activities, it was subsequently reorganized and developed under the directorship of George Nazos (1891–1924), whose appointment led to an abrupt ‘Germanization’ of the curriculum, with the championing of French and particularly German music at the expense of Italian-trained Greek composers. It also led to the establishment of the Athens Conservatory Orchestra in 1903 (Romanou, 2006, 131–2).3 The orchestra’s concerts, under the leadership of Filoktitis Economidis, José de Bustinduy and Jean Boutnikoff, exposed the Athenian public to western European orchestral and chamber music. Although the conservatory was organized according to European educational principles, teaching standards remained low, and the orchestra’s performances steadily deteriorated because of insufficient rehearsal time and the musicians’ parallel engagements in opera and operetta companies (Leotsakos, 2001, 350). The conservatory primarily served the musical education of the upper social classes, thus preserving privileges and social inequalities (Motsenigos, 1958, 328), and this exclusivity and social snobbery on the part of the musical establishment would later encumber Skalkottas’s career to a significant degree.

The turn of the twentieth century saw an intellectual revival, resulting from a cultural and artistic influx from western Europe and the rise of national self-awareness, and for the first time mainland Greek composers consciously attempted to establish a national musical identity. They were influenced by the linguistic struggle between advocates of the artificial katharevousa as the language of the upper classes, and supporters of the vernacular, demotiki, spoken by the majority of the population. This struggle was played out in the works of poets such as Kostis Palamas (1859–1943) and Angelos Sikelianos (1884–1951), who fought for the dominance of the demotiki Greek language, and by literary journals such as Noumas and Eleftheri Skini. Similarly, the composer George Lambelet (1875–1945), in his essay ‘The National Music’ (1901, 82–90), invited Greek composers to be inspired by folk-song, while Manolis Kalomiris (1883–1962), the doyen of the Greek National School and a powerful cultural figure,4 set the ‘manifesto’ of this school in the programme notes of his first concert in Greece (11 June 1908), arguing that ‘Greek music should find its roots, on the one hand, in the music of our pure folk songs, and, on the other, it [should be] decorated with all the technical means which we were granted through the constant work of the musically developed nations, and first of all the Germans, French, Russians and Norwegians’ (Anoyianakis, 1960, 581). Kalomiris and his followers were vehemently opposed both to earlier Greek – mostly Ionian – composers, whom they rejected as ‘Italianate’, and to modernist composers such as Dimitris Mitropoulos (1896–1960) and Skalkottas.

It was at this time of considerable political, social and cultural change that Nikos Skalkottas was born into a working-class family, albeit a musical one. His great-grandfather Alekos was a folk singer and violinist from the Cycladian island of Tinos. His grandfather Nikos, while still young, moved to the island of Evia, where he married local girl Marigo Konstandara (Papaioannou, 1997, vol. 1, 54). Skalkottas’s father, Alexandros (Alekos), was a self-taught flautist who played in the Philharmonic Band in Chalkis, the capital of Evia, together with his (also self-taught) violinist older brother Kostas, who became director of the city’s Philharmonic Society in 1896 (Jaklitsch, 2003, 136–7). Skalkottas’s mother, Ioanna Papaioannou,5 was a domestic servant for a rich household in Chalkis, where his father also worked as a gardener. It was in a room in this wealthy employer’s house that Nikos was born on 21 March 1904.6 His sister Angeliki (Kiki) was a later addition to the family. At the age of five, Nikos started violin lessons with his father, who allegedly helped him to build a small violin (Papaioannou, 1997, vol. 1, 62); he later continued lessons with his uncle Kostas. A few years later the family moved to Athens, although the reasons for this and the exact date are uncertain.7 They appear to have had a difficult time in the capital, and until 1916 they frequently moved house around Metaxourgio, a lower working-class neighbourhood of Athens.8

On 17 September 1914, aged 10, Skalkottas passed the Athens Conservatory violin entrance exam, and he was immediately placed in the intermediary grade in the violin class of the German professor Tony Schultze.9 Coming from a rather poor family of unschooled musicians, he received free tuition, with funds from the Averof scholarship.10 His progress was impressive, and only two years later (1916–17) he advanced to the higher grade in his violin class and for the first time played second violin in the Conservatory Orchestra, appearing at several evening student concerts; in 1918–19 he moved to the viola section, and finally to the back desks of the first violins.11 His talents were soon to be further rewarded in a series of competition prizes,12 culminating in his final year with a monthly stipend of 500 drachmas from the Averof fund, given on account of his ‘unusual musical talent’, and in addition to his free tuition (AthConsDM, 1919–20, 12). Skalkottas graduated in 1920, aged 16, having excelled in his final exams and being awarded the gold medal of Andreas and Iphigenia Syngros (AthConsDM, 1919–20, 128). His graduation performance took place at the Athens Municipal Theatre on 25 May 1920 during the Athens Conservatory Orchestra’s last concert of the season; the programme included, among other pieces, the first movement of Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. On the recommendation of Nazos, Skalkottas was awarded a further Averof scholarship for the continuation of his studies abroad, which started the following academic year, 1921–22, after the return from Berlin of another scholarship holder, Antigoni Kopsida (AthConsDM, 1920–21, 10; ME10, 14).

Although the conservatory’s funding was vitally important to Skalkottas because of his family’s difficult financial situation, it had the unintended consequence of emphasizing his disadvantaged position and his low social status, thus reinforcing difference and discrimination within the institution. It also influenced his future within Athenian professional musical circles, by assigning him to the class of ‘the proletariat of the music players’ (Kostios, 2008, 198).13 Despite Skalkottas’s apparently exceptional talent, he was not promoted as a soloist (as other students were, for example Mitropoulos);14 he appears not to have been given recital opportunities in the conservatory’s concert hall in Athens, unlike other privileged but less talented graduates,15 and was only allowed to play in the back desks of the orchestra. The adolescent Skalkottas felt excluded and disappointed, and he revealed his dissatisfaction with the musical establishment in a letter to the composer and conservatory professor Marios Varvoglis, whom he considered ‘the most musical, the most unspoiled person inside this villainous clique of our conservatory’;16 perhaps unwisely he advised Varvoglis that he should ‘for God’s sake be aware of the others’. On his graduation, and in order to survive financially, the talented but poor Skalkottas had little choice but to earn a living playing the violin at a variety of functions and in cafés in Athens and elsewhere,17 where he received enthusiastic reviews for his performances (ME2, 14). Painfully aware of his situation, in a letter to the correspondent of Musiki Epitheorisis he wrote: ‘I don’t want to be and I’m not one of those people who feel flattered in the courtyard of the cafenion [coffee house] and are getting lost in the idea of wealth.’ (ME10, 14). His perennially difficult financial circumstances would become a lifelong concern and a recurring theme in all his correspondence.

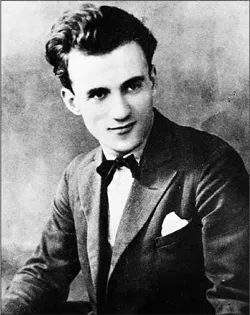

Illustration 1.1 A youthful Nikos Skalkottas