- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Barriers and Accident Prevention

About this book

Accidents are preventable, but only if they are correctly described and understood. Since the mid-1980s accidents have come to be seen as the consequence of complex interactions rather than simple threads of causes and effects. Yet progress in accident models has not been matched by advances in methods. The author's work in several fields (aviation, power production, traffic safety, healthcare) made it clear that there is a practical need for constructive methods and this book presents the experiences and the state-of-the-art. The focus of the book is on accident prevention rather than accident analysis and unlike other books, has a proactive rather than reactive approach. The emphasis on design rather than analysis is a trend also found in other fields. Features of the book include: -A classification of barrier functions and barrier systems that will enable the reader to appreciate the diversity of barriers and to make informed decisions for system changes. -A perspective on how the understanding of accidents (the accident model) largely determines how the analysis is done and what can be achieved. The book critically assesses three types of accident models (sequential, epidemiological, systemic) and compares their strengths and weaknesses. -A specific accident model that captures the full complexity of systemic accidents. One consequence is that accidents can be prevented through a combination of performance monitoring and barrier functions, rather than through the elimination or encapsulation of causes. -A clearly described methodology for barrier analysis and accident prevention. Written in an accessible style, Barriers and Accident Prevention is designed to provide a stimulating and practical guide for industry professionals familiar with the general ideas of accidents and human error. The book is directed at those involved with accident analysis and system safety, such as managers of safety departments, risk and safety consultants, human factors professionals, and accident investigators. It is applicable to all major application areas such as aviation, ground transportation, maritime, process industries, healthcare and hospitals, communication systems, and service providers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Accidents and Causes

Accident, n. An inevitable occurrence due to the action of immutable natural laws.

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary, ca. 1906.

Introduction

Let me start by describing an accident that happened as I was working on the introduction to this book. There is no special reason for taking this accident as an example, except for the fact that it did take place. In that sense it is typical of the multitude of accidents that happen all the time. Whenever I open a newspaper, listen to the radio, or log on to the Internet, I can most likely find another accident that will serve just as well. Certainly, not a single week goes by without a major accident grabbing the headlines across the media, nationally and internationally.

In this case it was a bus accident that happened in the port of Gedser, Denmark, on May 28, 2002. A double-decked bus that had arrived to Gedser on the ferry from Travemünde, Germany, drove into a roof over a customs booth with the result that the upper deck of the bus was severely damaged; four people were killed and 18 were taken to nearby hospitals. The bus was firmly wedged under the roof, which covered the lanes for private cars and small trucks. Buses and large trucks were supposed to use a different lane, and the driver had missed three signposted warnings about the limited height ahead.

When something like this happens the inevitable question is what went wrong, and what the cause was. In many accidents of this type there is no simple or single cause, for instance in the sense that something failed. There are rather a number of things that go wrong and which together lead to the accident. In this case the driver clearly did not notice the signs, either because they were not clear enough or because he did not pay sufficient attention. (The alternative, that the driver noticed the signs, but then wilfully ignored them, is rejected as being too improbable. Such deliberate malicious actions are usually excluded from accident analysis.) One may then wonder why that happened. One reason for the lack of attention could be that the driver followed the cars in front instead of trying to find his way independendy. (That then leads to some thoughts about why the driver was inattentive, where possible factors may have been the time of day, insufficient rest after a long period of driving, eating a heavy meal during the short ferry trip, etc.) These speculations illustrate the step-by-step backwards reasoning that is typical of reactions to accidents.

This accident also shows the importance of barriers. Very briefly, a barrier is something that can either prevent an event from taking place or protect against its consequences. Since this was a potentially dangerous situation — a hazard — a set of barriers had been installed (not least because a number of similar accidents had happened previously). The barriers included signs and indications (for instance, showing lanes for different types of vehicle), the standard warning signs such as limited height ahead, active warnings in the form of blinking signals triggered by a photocell, etc. Despite these barriers the accident happened. Sometimes the barriers fail themselves, for instance, because a lamp does not light, a sensor does not register, or a sign is so dirty that it cannot be read or is covered by, e.g., branches and leaves. None of this was the case in this accident. How can we then understand what happened?

After the accident the roof over the customs booth was immediately removed. (Since the customs booth was no longer used, it could easily have been removed earlier, thereby rendering the accident impossible.) That does not eliminate the possible causes, but it removes the hazard, hence making another accident of this type impossible. The example illustrates that accidents often are due to the combination of an existing hazard (the low height of the roof) and an unexpected event (the driver’s presumed inattention). This will be taken up later in the book in the discussion of accident models and the relation between barriers and accidents.

Accidents today rarely happen just because one thing goes wrong, i.e., there are very few cases of single cause failures. Engineers and designers have learned to guard effectively against such conditions and single failure prevention is often part of formal system requirements. This, however, does not rule out accidents that happen when two or more failures occur together, as when a simple performance failure combines with a weakened or dysfunctional barrier. Such combinations are much harder to predict than single failures, and therefore also harder to prevent. Since the number of combinations of single failures can be exceedingly large, it is usually futile to prevent multiple failure accidents by a strict elimination of individual causes. A much more efficient solution is to make use of barriers, since the effectiveness of a barrier does not depend on knowing the precise cause of the event. A fire extinguisher or a sprinkler system, for instance, is an effective barrier against fires regardless of their origin.

What is an Accident?

This book is about the role of barriers in accident prevention, although it also ventures some thoughts on the nature of accidents as such. Despite Ambrose Bierce’s bitter definition — which in some sense anticipates both Murphy’s Law and Charles Perrow’s (1984) notion of natural accidents — accidents are not inevitable. Although it is impossible in practice to prevent every accident, it is fully possible to prevent many and perhaps even most of them. To do so requires that we understand why accidents really happen, so that we can find the most effective ways of guarding against them. This means that we must refrain from taking existing ways of explaining accidents for granted, and instead reflect a little on what takes place during accident analysis and investigation. The argument made in this book is that we need to change our understanding of what accidents are, in order effectively to prevent them.

The book is, in particular, about understanding the role of barriers in accidents. This can be interpreted in two different ways, which both are described further in the following. First, that the failure or absence of a barrier or of several barriers, may be part of why accidents occur. Second, that the existence and proper functioning of a barrier may reduce accidents and their consequences either by preventing unexpected events from taking place or by protecting people from the consequences if the former effort fails. Even when protection cannot be complete, it may be possible to alleviate the effects, hence ensure that the outcome of the accident is not as serious as it could have been. Both aspects will be considered in this book, the first in connection with analysing and explaining accidents, the second in connection with preventing accidents.

A Little Etymology

Etymology is the branch of linguistics that deals with the origin and historical development of language terms (words) by tracing their transmission from one language to another, beginning with the earliest known occurrence. Although it may sound trivial, it is usually well worth the effort to look into the meaning of words, and in particular into how that meaning has developed.

Everybody knows what an accident is. That, at least, is what we assume. But experience shows us that it can sometimes be dangerous blissfully to make such assumptions since it misleads us into talking about things without properly defining what we mean. Even if everybody knows what the word ‘accident’ means, in the sense that they recognise it and can associate something to it, it does not follow that everyone shares the same understanding of what an accident is. It is therefore prudent to spend some time to discuss the meaning of the words and to begin by exploring their origin.

From the linguistic point of view, the word accident is the present participle of the Latin verb accidere which means ‘to happen’, which in turn is derived from ad- + cadere, meaning to fall. The literal meaning of accident is therefore that of a fall or stumble. The derivation from ‘to fall’ is significant, since falling is not something one does on purpose. If someone falls while walking or while climbing, it is decidedly an unexpected and unwanted event. It is, in other words, what we call an accident: an unforeseen and unplanned event, which leads to some sort of loss or injury.

Other definitions of ‘accident’, such as they can be found in various dictionaries, concur that an accident is an unforeseen and unplanned event or circumstance that (1) happens unpredictably without discernible human intention or observable cause and (2) leads to loss or injury. Used as an adverb, to say that something happens accidentally or happens by accident means that it happens by chance, i.e., without will or intention — and usually also without any expectation that it will happen (at least at that particular moment in time). We may therefore also talk about an accidental occurrence with unwanted outcomes. Similarly, we often say that someone suffered an accident or was the victim of an accident. An ‘accident’ can thus refer to either an event, the outcome of an event, or the possible cause. This unattractive quality is characteristic of other important terms as well, for instance ‘human error’ (cf. Hollnagel, 1998). To reduce the possibility of confusion, the term ‘accident’ shall in this book be used to refer to the event, rather than the cause or the outcome.

According to this definition an act of terror is not an accident, since the outcome is brought about on purpose. The prevention against acts of terror is therefore different from accident prevention since security must consider not only the occurrence of unwanted outcomes but also that these are deliberately brought about. There are nevertheless significant areas of overlap between safety and security, particularly when it comes to protecting third-party recipients against unwanted outcomes.

It is interesting to note that in the Germanic languages the word for accident comes from the Low German ungelucke meaning lack of luck [(ge) lucke]. In modern German the corresponding word is unglück, in Swedish olycka, and in Danish and Norwegian ulykke. If you fall or stumble you are, of course, out of luck. The word luck itself is possibly related to the word loop, signifying something that is closed or locked, or something that has come to a completion — presumably a successful one. So while accident in its etymology refers to the event itself, lack of luck (ungeluck) refers to the condition or state where accidents happen, the background or cause, so to speak. Indeed, one has an accident because one is out of luck.

Since we are looking at the meaning of words, and since this book is about barriers as well as accidents, it is appropriate to consider also the origins of the term barrier. Here the situation is a litde easier, since the word is the same in the Latin and Germanic languages.

A barrier is derived from the middle age Latin word barra, which we also find in the English word bar (as in a bar, but not the place where you drink). A barrier is something that stops, or is intended to stop, the passage of something or someone, usually in a physical sense. So if an accident refers to an event, a barrier refers to that which can prevent the event from taking place.

Definition of Accident. For the purpose of this book, an accident can be defined as a short, sudden, and unexpected event or occurrence that results in an unwanted and undesirable outcome. The short, sudden, and unexpected event must directly or indirectly be the result of human activity rather than, e.g., a natural event such as an earthquake. It must be short rather than slowly developing. The loss of revenue due to an incorrect business decision can therefore not be called an accident, regardless of how unwanted it is. It must be sudden in the sense that it happens without warning. The slow accumulation of toxic waste in the environment is not considered as an accident since in this case the conditions leading to the final unwanted outcome — the disruption of the ecology — were noticeable all along. The final outcome is therefore neither sudden nor unexpected and should more properly be called misfortune, decline or deterioration. In contrast, a collision between two cars in an intersection is short, sudden, and unexpected — and also has an unwanted outcome. Some accident definitions also add that the event must be unintended. This is not done here, for the simple reason that if an event is unexpected then it must also be unintended. Intention is nevertheless related to the understanding of accidents, as it will be discussed below.

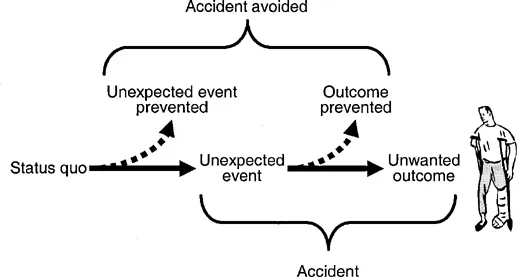

If we consider the above definition as a basis for thinking about prevention, it is clear that this either can be directed at the event or at the outcomes. Since an accident is the event plus the outcome, it follows that if we can prevent the event from taking place, we will also have ensured that the outcome does not occur. However, as illustrated by Figure 1.1, even if we cannot prevent the event from taking place, we may still be able to prevent the outcome from occurring. Preventing the accident from happening thus altogether means ensuring that the recipient comes to no harm. In Figure 1.1 the recipient is shown as a person, but it may of course equally well be a social system, a technological artefact or a combination thereof.

Before going any further it is also necessary to define what is meant by a system. The term is ubiquitous in technical (and popular) writing today and is generally used on the assumption that it is so well understood by everyone that there is no need to define its meaning. While this may possibly be so, it never hurts to be on the safe side. In this book the term system is therefore used to mean the deliberate arrangement of parts (e.g., components, people, functions, subsystems) that is instrumental in achieving specified and required goals.

It is legitimate to call a pair of scissors a system. But the expanded system of a woman cutting with a pair of scissors is also itself a genuine system. In turn, however, the woman-with-scissors system is part of a larger manufacturing system — and so on. The universe seems to be made up of sets of systems, each contained within a somewhat bigger, like a set of hollow building blocks. (Beer, 1964, p. 9)

As this delightful quote makes clear, the scope of a system depends on the purpose of how it is described. Any system can be seen as including subsystems and components, just as any system can be described as a component or part of a larger system.

Figure 1.1: The constituents of an accident

Accident versus Good Luck. It is clear that an accident involves more than just an unexpected event. To see that we only need to look at unexpected events where the outcome is desired rather than undesired. The simplest example is winning in the lottery — or suddenly being given a sum of money in the case of those who do not play the lottery. More generally, think of a situation where something happens that is positive...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1: Accidents and Causes

- Chapter 2: Thinking About Accidents

- Chapter 3: Barrier Functions and Barrier Systems

- Chapter 4: Understanding the Role of Barriers in Accidents

- Chapter 5: A Systemic Accident Model

- Chapter 6: Accident Prevention

- Bibliography

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Barriers and Accident Prevention by Erik Hollnagel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.