![]()

Chapter 1

Simulation and Technology in Legal Education: A Systematic Review

Paul Maharg and Emma Nicol

Introduction

This chapter is a systematic review of the literature on simulations and technology in legal education. To date, there has been no reasonably comprehensive summary of the research on simulation in this context – in spite of a growing body of evidence that games and simulation not only have positive effects on student learning, but that there are also significant correlations between the use of educational technology and student engagement. The practice of systematic reviews generally is relatively rare in legal education, in common law jurisdictions at least. Indeed, systematic reviews as a whole, such as that of Mearns et al. on the effectiveness of online and blended learning in the field of education and technology, are not widely available in law as a discipline, nor are they evenly distributed in law’s sub-domains.

In the following review we describe our search strategies and the dataset that resulted from our search. We then outline some of the main findings and comment on the robustness of the findings. Finally we propose a research programme for future studies in simulation and technology in legal education. At the outset we should note that because the dataset will be much larger than the normal collection of citations in this book, we have, with the approval of the editors, moved from the housestyle (OSCOLA) and have used the Harvard (APA) citation system, with name and date in the body of the chapter and full references given in the reference section entitled ‘Review dataset’ at the end of the chapter. All other chapter references are set out as per the same format, but in footnotes in order to separate them from the dataset.

Search and Classification Procedures

A systematic review requires an answerable question. We began the process intending that we would analyse the literature for the characteristics of good simulation practice and that the analysis would take the form of a meta-review – effectively a statistical analysis of the data derived from the literature that would provide a standardized approach for analysing prior findings. However, we quickly encountered a fundamental issue. The key challenge in writing this chapter has not been the quantity of the literature. Indeed, for a specialized topic such as this, there exists a relatively substantial body of literature. The main problems we encountered derived from the variation and quality of the literature. These included lack of relevant data, including statistical analyses, insufficient specificity on description and analysis of the educational intervention, wide variation in information on the quality of learning and lack of detailed analysis of findings. Randomized clinical trials, including cluster-randomized trials, are generally recognized as providing the least-biased estimates of intervention effect – there was not a single example of this in the literature under review, almost no reliable statistical studies and within those items that had undertaken literature reviews, the general quality of them was not robust. A prior analysis was therefore required: we needed to investigate the quality of the literature on simulation and technology. Our systematic review therefore focuses on this analysis.

Systematic reviews require explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria. Our time span is 1970–2012 – effectively 42 years. We searched the following common law jurisdictions: England and Wales, Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, Scotland, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Hong Kong. We searched only the literature published in English, including items translated into English and those in English in a foreign-language publication (e.g. Maharg 2007a [Dutch] and 2009 [Japanese]). Where we came upon items from civilian jurisdictions in English that referenced simulations in civilian and common law jurisdictions, we included these where possible. Searches were conducted using the following keywords and phrases: legal simulation education; legal simulation; digital simulation; transactional learning; mock courts; moot courts; mock trials; hypotheticals; and learning by doing. The following databases were searched: Westlaw; Lexis; SSRN; Heinonline; and Legal Journals Index. Jurisdictional bibliographies were also searched, as were topic-specific bibliographies. We reviewed items that were peer reviewed (though it was often unclear, particularly for the first two decades of our time span, how to determine which items had undergone peer review), as well as those that appeared to have undergone no peer review. Where we decided that a web-published item (e.g. on an author’s webpage or on SSRN) was sufficiently within the parameters of our review, we would include that, even if there were no formal publication. Where appropriate, we used search engines such as Google Scholar.

A critical issue for us was the definition of our three main terms: ‘simulation’, ‘legal education’ and ‘technology’. We construed our terms broadly, knowing that the field under analysis was fairly small, given the vectors of these three terms:

1. ‘Simulation’ was construed as any heuristic that involved the simulation of any aspect of legal theory or practice within a legal education context and for an educational purpose. Since our review covered theory as well as practice, we included work that discussed simulation as well as accounts of simulation interventions.

2. We defined ‘legal education’ widely as being at tertiary education or beyond and involving any legal matter. It became quickly apparent that the vast majority of the items in the dataset described simulations that took place in tertiary education, with a minority having taken place in a workplace setting. We also included continuous professional development. The few secondary or high school studies that were found during searches were deleted. We took a broad view of the subject matter included in this definition of legal education, including multi-disciplinary and interdisciplinary examples, e.g. legal studies embedded in or spliced with other subjects, such as philosophy or business.

3. ‘Technology’ was the most complex of the three terms to define. We defined it as incorporating the practice and/or discussion of any form of digital technology used in the design, implementation, assessment or analysis of simulation, and essential to the functioning of the simulation. Digital technologies could of course include video, photographs, maps and graphics as well as text. We excluded simulation studies where the only use of technology seemed to be the common use of everyday applications such as word processors to reproduce text and numbers. If these were included in our review, then the simplest word-processed hypothetical could claim a place. This was a matter of judgment, of course.

Clearly, given the chronological span of our search, we could not restrict our definition to online learning, and historically, in the period 1970–88 or so, it could be argued that word processors were innovative technologies. We therefore defined the digital element as essential for the reported simulation if a simulation were present in the item. In our definition of ‘online learning’, we were guided in part by the annual Sloan Consortium Reports, which, since 2002, have defined online learning as learning that takes place entirely or in substantial portion over the Internet.

Given these definitions and search vectors, it should be remembered that we are focusing on the intersection of all three search criteria. Thus, useful collections of items such as the US Journal of Legal Education’s Symposium on Simulations (Issue 4, 1995) are not included because there was no discussion of technology in the simulations under discussion.

Following initial searches, 238 items were identified as being potentially relevant from title and abstract descriptions. Full paper readings of each document then took place and 38 were discarded as not relevant according to the search criteria. There were 20 items for which the full text could not be sourced (stemming largely from the first decade or so of our search). Items were then assessed for the presence of a digital element to the simulation discussion (107 items). Items that were from non-common law jurisdictions were generally discarded, but during the course of searching, there were 11 publications referencing common law initiatives that we considered needed to be included because they described important aspects of simulation activity or theory, or referenced simulation initiatives in common law jurisdictions. Therefore, these have been included in the dataset. Five of these items originated from the Netherlands (Fernhout et al. 1987; Lodder and Verheij 1998 and 1999; Mayer et al. 2009; Verheij et al. 1997), one from the republic of Georgia (Nakashidze 2012) and one from Japan (Shibasaki and Nitta 1997). The items in the sub-set of 107 were largely published in the proceedings of legal conferences and in legal (and very often legal education) journals. There were also several final project and institutional reports, as well as a few articles from legal professional journal publications that we included. In addition to this, we included five review articles, bringing the total in the dataset to 123 items.

Results

Around half of the dataset consists of what one might call ‘overview’ items – that is to say, they outline possible uses for simulation in legal education, often dealing in detail with the use of simulation both in law and in other disciplines. They contain no specific description of a real example of the use of simulation in the classroom or elsewhere. A significant minority of the items found are descriptions of (or sometimes merely announcements about) simulations that are about to take place in a particular institution and the educational technology invested in rather than any information about their success or otherwise, or the resulting outputs.

Chronology

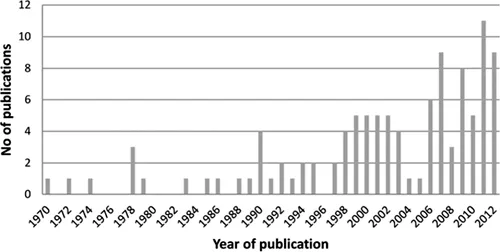

The graph below illustrates the chronological spread of items within our time span of 1970–2012.

Figure 1.1 Chronology of dataset items, 1970–2012

The rate of publication remained fairly low during the 1970s and 1980s at a rate of several items per year, with a small peak at the close of the 1970s. Peaks can be observed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, a reflection of the rise in interest in the Internet following the establishment of the first widely available web browser in 1993 (Mosaic and later Netscape). Another peak is seen in the mid-2000s, when Second Life and other virtual communities began to make their presence felt. Publication numbers have continued to increase steadily ever since, reaching a high of 14 publications in 2011, though we cannot correlate an increase in publication with an increase in simulation activity within law schools. Interestingly, though, among the non-digital items found in our initial search, few were published much earlier than 1970. There may be a relationship between simulation and the use of innovative delivery technologies. The recent increase in the number of items corresponds with the predictions of more general reports such as the annual Horizon Reports, which describe simulation as a heuristic as becoming increasingly more visible.

Geography

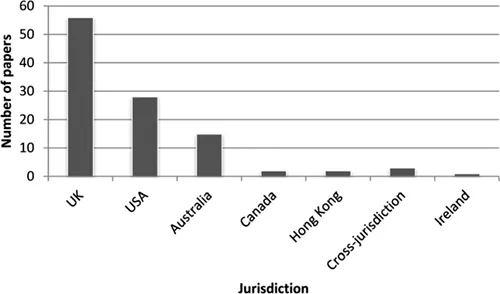

Geographically, items originate from six common law jurisdictions. The greatest number of papers originated in the UK, with 56, followed by the USA, with 28. A total 15 papers originated from Australia, two from Canada, two from Hong Kong and one from the Republic of Ireland. Two items were cross-jurisdictional (e.g. UK/Australia) and another, falling under this category, was written from a pan-EU perspective (Petzold 1999). Figure 1.2 above illustrates the geographical spread.

Figure 1.2 Geographical location of common law items

Simulation Data

A detailed summary of the information provided by the dataset on the structure of the simulations is set out below.

Year of study

Thirty-two of the items made specific reference to the year of study in which the simulation took place. The most commonly reported timeframe for a simulation to occur was during the year or years of postgraduate study. Twenty-one of the items reported simulations that took place during those years – it would appear that they were designed or run on vocational or professional programmes. Four items referred to simulations that took place during the final year of undergraduate study. Five items described interventions that took place during the first year of study (Ashley 2000; Crellin et al 2011; Munro and Noah 1978; Vaughn 1995; Yule et al. 2012) and a further two items described the use of simulations at various points of a degree-level programme (Garvey and Zinkin 2009; LeBrun 2003).

Description of data subjects

A striking feature of the dataset is the near-absence of any data that describes the age, gender, ethnicity or native language(s) of the participants. There is also close to no discussion of accessibility issues for learners or staff in the simulations.

Simulation in different curricula

Simulation can often be used as a platform to enable learning in places or at a distance where conventional learning would be problematic. One item described a simulation that was specifically designed for distance learning (Barnett and McKeown 2012), three that were cross-jurisdictional (Bradlow and Finkelstein 2007; Maharg and Nicol 2009; Maharg and Paliwala 2002) and five described simulations that took place in the workplace among recent graduates of law schools (Hemming 2006; Hutchinson 2006; Jabbari 2000; Line and Hemming 2007; Macoustra 2004), with four of these items published in the last decade. Gould et al. (2008) describe the development and evaluation of a simulation engine, the Simulated Professional Learning Environment (SIMPLE). The eva...