![]()

Chapter 1

Witches, Catholics, Scolds, and Wives: Noisy Women in Context

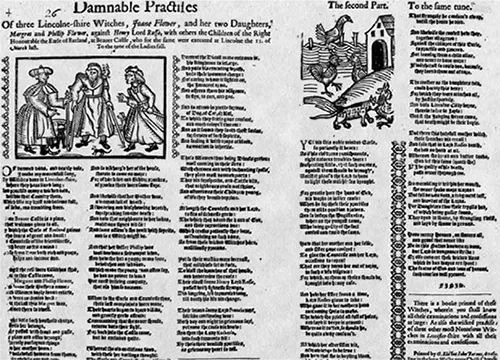

Less than a year after the March 1618 assizes, two accounts of the witchcraft trial and execution of Joan Flower and her daughters in rural Lincolnshire appeared in the bookshops of central London. One was a broadside ballad titled Damnable Practises that related the women’s crimes through poetry, popular song, and public performance (see Figure 1.1). Printed at the bottom of the broadside is the following advertisement:

There is a booke printed of these Witches, wherein you shall know all their examinations and confessions at large: As also the wicked practice of three other most Notorious Witches in Leceister-shire with all their examinations and confessions.1

The “booke printed of these Witches” refers to the trial account of the Lincolnshire case published just months ahead of the broadside by the same printer, George Eld, at his shop in “Fleete-lane, at the signe of the Printers Presse,” and sold by the same bookseller, John Barnes, at his store “in the long walke neere Christ-Church.”2 The ad on the broadside was a cross-promotion to not only increase profits but to also direct ballad consumers to other sources of information about these sensational crimes. When examined in tandem, it is clear the broadside ballad drew quite heavily on the trial account for the details of the Flower family’s crimes, down to the exact blasphemous and abusive language in which the women were reported to have engaged. The free exchange of information between these two popular print genres—trial account and broadside—is just one example of the ways in which stereotypes about the acoustic properties of disorderly women were disseminated to seventeenth-century English citizens. Beyond court reports and broadsides, early modern consumers had a wealth of other sources from which to draw their knowledge of female transgression and its musico-acoustic properties. This tangled collection of cultural sources about women, disorder, sound, and witchcraft—including sermons and religious tracts, law, popular song, street literature, and folklore—is the raw material from which broadside authors assembled their details, opinions, and stereotypes. This chapter parses out the disparate threads of knowledge available to cheap print consumers about women, witches, and murderesses, and the subtleties of their crimes through a systematic examination of Protestantism and social disorder, domestic violence, scolding, misogynist pamphlet literature, demonological treatises, anti-Catholic invective, and the grotesque. These writings form the cultural milieu within which the broadside ballad was situated, and constitute the source material from which its authors drew for their acoustic characterizations of dangerous women.

Source: Magdalene College Pepys 1.132–133.

Figure 1.1 The broadside ballad Damnable Practises © Magdalene College, Cambridge. Reproduced with permission

The law made clear distinctions between the various crimes of these disorderly women.3 Witchcraft, the most egregious, was classified as a pact with the devil. In England, however, witches were most often accused of malfeasance, or the capacity to do harm or destruction to property through occult means.4 Witch accusations were patterned in early modern England, and, as “first-wave” witchcraft scholars Keith Thomas, James Sharpe, and Alan Macfarlane have noted, generally centered on women who were economically marginalized (poor), old (widowed), or otherwise outside patriarchal control.5 Women who committed petty theft, avoided church services, murdered or even merely scolded their husbands, were prone to drunkenness, or were in any way a social nuisance were at risk of also being identified as a witch.6 Even the law profiled female criminals by designating special punishments for women who committed capital offenses, a manifestation of the perceived severity of their crimes against social order.7 While women were underrepresented in violent crimes in early modern England—instead accused more often of petty crimes, scolding, or domestic disturbances—witchcraft was the exception. Violent crimes like murder and lesser domestic offenses, however, were still intimately connected to the crime of witchcraft. According to legal statutes, for instance, murdering a husband, master, or newborn through witchcraft was a capital offense.8 Witchcraft commanded distinct legal status apart from other female crimes and inspired an impressive corpus of extremely subjective literature including a fair amount of misogynist invective. As Marion Gibson has written, the “definition of witchcraft and of what it means to be a witch … depended in part on stereotypes rather than individual ‘realities.’”9 These “stereotypes” of female criminals were disseminated through a mixture of superstition and erudition, as well as perceived cultural fears and anxieties. Anti-Catholic sentiment, hysterical treatises, pamphlets and trial accounts detailing murder and witchcraft, grotesque satire, folkloric traditions, and Puritanical invective bombarded the early modern consumer. Though the lines separating female criminals were legally discrete, differentiations could still be quite blurred in the popular consciousness when we consider the cases of devil-conquering scolds, harsh-tongued husband murderers, and homicidal witches as represented in pamphlets, treatises, broadsides, and theatrical works.

The Controversy Over Women

Many economic and religious changes during the seventeenth century were responsible for increasing the perceived fears about women, witchcraft, and social disorder. These anxieties were articulated in sermons, religious tracts, didactic literature, and social commentary. For instance, populations were expanding, available land was in short supply, and poverty and vagrancy were widespread, leading to an increased number of marginalized and vulnerable citizens ripe for suspicion of occult crimes.10 Other economic factors contributed to the cultural anxiety over the changing perceptions of gender roles. Some historians postulate that economic changes restricted women’s independence, citing fewer women represented in business pursuits after 1500.11 Others suggest the rise in capitalism and the subsequent decline in neighborly relationships and social harmony was also responsible for an increase in witch accusations and incidences of domestic scolds.12 Religious tension between Puritans and Catholics also heightened concern over the breakdown of the family unit, the cornerstone of a well-ordered society, and suspicions of Popish practices such as strange languages (Latin) and transubstantiation (ecclesiastical magic) were on the rise. Fervent anti-Catholic literature also went as far to equate practitioners of Latin rites with witches, the grotesque, and chaos.13

Family dynamics in the Protestant home were a metonym for social hierarchies. Church teachings strengthened patriarchal authority, and shifted the burden of maintaining order in one’s personal “kingdom,” or the home, on husbands and fathers. Puritan Philip Stubbes lamented the current state of cultural disorder when he wrote: “Was there ever seen less obedience in youth of all sorts, both menkind and womenkind, towards their superiors, parents, masters and governors?”14 The hierarchical relationship between the subjects named here by Stubbes—husband, wife, children, servants, masters—were paramount to the stability of well-ordered society.15 Order in the family represented order in the state. William Gouge commented that it was “necessary … that good order be first set in families: for as they were before other polities, so they are somewhat the more necessary: and good members of a family are like to make good members of Church and common-wealth.”16 While the man was “a king in his own house,” women, not entirely subservient, were expected to maintain order in their home, educate their children, and, above all, maintain a modest demeanor.17 A brawling, verbally abusive, extravagant, or overly assertive wife constituted a threat to the social order and could be subject to correction by the law or through the community, usually by public shaming.

The flood of misogynist literature, often referred to by twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholars as the “English controversy over women,” reiterates these fears and identifies the locus of transgression primarily as the woman’s voice.18 Philip Stubbes hinted at the current lack of orderly conduct by women in his text A Christal glasse for christian women when he wrote that women of days past would never “gossip,” “banquet or feast,” or “scold or brawle, as many will now a daies for every trifle, or rather for no cause at al.”19 In his A Preparative to Marriage, Henry Smith writes that man must “guide his mouth wisely” such that the “wordes of his mouth have grace.” One should choose a wife who exercises the same discretion. The “right” wife should “openeth her mouth with wisedome, & the lawe of grace [should be] in her tongue. As the open vessels were counted uncleane; so account that the open mouth hath much uncleannes.”20 Misogynist pam...