![]()

1

The Right to Landscape: An Introduction

Shelley Egoz, Jala Makhzoumi and Gloria Pungetti

Background

In the course of its development, the idea of landscape has been embraced by many disciplines and used to frame scientific, political and professional discourses. The Right to Landscape is yet another framing, offering a particular discourse on landscape and human rights. The concept of the right to landscape explores in detail the role of landscape in working towards justice and human wellbeing. This is especially pertinent, we believe, for those who are engaged in research and actions that influence the form and function of the landscape. For us the editors, landscape architects Shelley Egoz and Jala Makhzoumi, and scholar of holistic landscape Gloria Pungetti, the prolific multidisciplinary body of literature on landscape forms the theoretical foundation and inspiration for the necessary visionary thinking needed to address planning, design and management of landscapes. As landscape architects whose passion, research interests and practice revolve around ethics and social justice related to the designed space, Shelley Egoz and Jala Makhzoumi sought the Cambridge Centre for Landscape and People (CCLP) that was founded by Gloria Pungetti as the ideal platform for this initiative that explores the interface of landscape and human rights.1 CCLP’s mission statement is to: “integrate the spiritual and cultural values of land and local communities into landscape and nature conservation and socioeconomic needs into sustainable development; and to support biological and cultural diversity, as well as awareness and understanding of, and respect for, landscape and nature” (CCLP, 2010a). Within this mission the initiative of the Right to Landscape (RtL) “seeks to expand on the concept of human rights and to explore the right to landscape”. RtL proposes the premise that “Landscape, as an umbrella concept of an integrated entity of physical environments, is imbued with meaning and comprises an underpinning component for ensuring wellbeing and dignity of communities and individuals”. The aim of the initiative is “to collectively define the concept of the right to landscape and to generate a body of knowledge that will support human rights” (CCLP, 2010b).

The RtL initiative was launched in December 2008, on the 60th anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, with an international workshop collaboratively organised with CCLP and held in Jesus College, Cambridge, UK. The multidisciplinary workshop began the discourse and ideas that are explored in this book. The volume begins with discussions on the idea of the right to landscape. The following chapters include a range of international case studies that explore the interface of landscape and human rights from their respective academic and/or professional position. By presenting case studies that illustrate how landscape and human rights depend on and affect each other we aim to yield discourse that includes different perspectives, needs and realities, and disseminate ideas on the right to landscape. While these essays are not by all means an exhaustive collection on this topic or a representative international model, they form the first step within our vision for ongoing dialogue on the right to landscape. We hope to see this framework supporting and facilitating interdisciplinary research by adding to and contributing towards the development of policies that will sustain human rights and secure the wellbeing of people and the landscapes they inhabit.

Landscape and New Challenges to Human Rights

Twenty-first century threats to landscape have been acknowledged in particular relation to climate change (Erhard, 2010). Environmental conditions linked to the phenomenon and their impact on species and human habitats through desertification, extreme weather events causing flooding, as well as rising sea levels inflicting disasters, are a topic of concern in scientific and political international discourse. An alarm about the degradation of the physical environment and the need to take measure for its protection began before this contemporary widespread occupation with climate change.

During the past few decades several international organisations adopted various interpretations of landscape to describe their mission and philosophies. The International Association for Landscape Ecology (IALE) represents a scientific approach to landscape aiming “to develop landscape ecology as a scientific basis for analysis, planning and management of the landscapes of the world” (IALE, 1998). The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Committee’s definition, on the other hand, endeavours to overcome the perceived dichotomy between “cultural” and “natural” landscapes by “represent[ing] the combined work of nature and of man” (UNESCO, 2005: 83). Both the above examples address landscape as the physical result of process, whether natural or human driven. Underpinned by a quest for the wellbeing of all humans, one can argue that the above missions assert a universal right to a healthy environment and legacies of heritage. Heritage indeed includes intangible attributes but the foci of such bodies have been on protection of the actual tangible dimension of particular landscapes deemed culturally or historically significant. Within official international organisations, the value of the ordinary landscape as an everyday human habitat was not recognised until the turn of this century when the Council of Europe introduced the European Landscape Convention (ELC).2

The ELC represents a significant development perhaps best captured in its definition of “landscape” as “an area, as perceived by people, whose character is the result of the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors” (ELC Article 1a). Positioning the role of human perception is the critical dimension here, as Kenneth Olwig argues in this volume. Moving the realm of landscape from a scientific objective arena to one that is in flux is an acknowledgement of the complicated nature of the concept and inevitably raises questions of potential ideological tensions and the imperative of an association between landscape protection and matters of social justice. This is no coincidence keeping in mind the time when the Council of Europe was established – post World War II and the organisation’s primary concerns with maintaining democracy and human rights. Human rights discourse has since widely diffused in particular within the last few decades of globalisation where these matters have reached the developing world (Cowan et al., 2001). Cowan et al. have also argued that the model for human rights has become hegemonic and saw a need to explore tensions between local and global conceptualisations of rights. They recognised the emergence of new fields of political struggle “such as reproductive rights animal rights and ecological rights” (Ibid.: 1). Today, a decade later, the accelerated pressure on limited resources and competition that is bound to inflict further conflict necessitates a new way of framing human rights. Underpinned by a moral imperative for aspiring to social justice in a challenging physical and political environment we explore how landscape as an overarching concept can form a new context to address such contemporary challenges.

Landscape as a Framework for Addressing Human Rights

Launching the right to landscape discussion on human rights repositions an already extended interpretation of the term landscape in a new political arena. The word landscape has proven difficult to define (Williams, 1973; Meinig, 1976) and the variety of readings and uses of landscape attest to the elusive nature of this idiom (Makhzoumi and Pungetti, 1999). It has been generally agreed that the word bears different meanings to different people in different contexts. Nevertheless, in the past few decades the use of landscape as a theoretical instrument has become common in a multitude of disciplines and “has created the basis for a ‘reflexive’ conceptualization of landscape” (Olwig, 2000: 133). Landscape as the foci or as the envelope for theory and application can thus be found from cultural geography to ecology and in a diversity of humanistic fields such as anthropology, environmental, cultural and visual studies, history, tourism, archaeology, heritage and the design professions, especially landscape architecture. Paradoxically, the vagueness and difficulty on an agreed definition has not become a limitation but offers opportunities for innovative thinking by adopting the expansive, holistic framework of landscape. It is precisely this elasticity that makes landscape a potent term to explore new theories that relate to the value of landscape. By extending the spatial social arena to embrace political ethical ones, we explore ways in which landscape could become a positive tool to promote social justice.

Social justice and landscape is not a new topic. Several scholars have examined landscape in that context. Denis Cosgrove (1984) introduced the social class perspective into the landscape discourse.3 James Duncan (1990) interpreted landscape as a cultural production correlated with political power. W.J.T. Mitchell (1994) too made the link between power and landscape. Don Mitchell (2000) advocated for critical geography through which he endeavours to stimulate action for cultural justice. At the same time Michael Jones’ work was concerned with landscape, law and justice (Peil and Jones, 2005) and he continues to explore their significance in terms of the European Landscape Convention (Jones and Stenseke, 2011). Kenneth Olwig (2002 and 2009) writes prolifically on landscape ideology, law and nationalism – topics that are directly related to the subject of landscape and human rights. The work of anthropologist Barbara Bender has been pivotal in instigating the discussion on landscape and social justice in non-Western cultures (Bender, 1995; Bender and Winer, 2001). Addressing the political dimension of landscape, her work has inspired anthropologists and archaeologists to expand beyond tangible, spatial dimensions and explore landscape as a repository of culture in a specific place and time (Tilley, 2006).

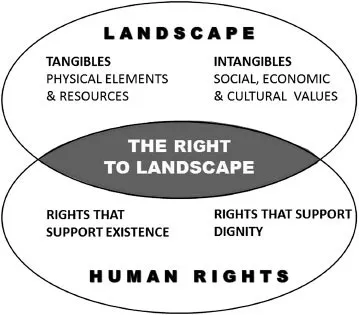

Humans have shaped their surroundings, creating cultural landscapes, since the Neolithic revolution. Land has been cultivated to yield produce, woodlands cleared and managed whether for pastoral uses or fuel, environments formed for habitation and settings created for pleasure. Landscape therefore is simultaneously a product such as arable field, pasture land, settlement and garden, and, the act of production embedding intent, design and action. More so, it is a conceptualisation of both product and production. As the product of people – environment co-evolution, landscape is at once “a tangible product” of the act of humans’ shaping their surroundings and “intangible process”, making sense of the world through shared meanings and values (Makhzoumi, 2009b: 319). Part nature part culture, landscape straddles both realms. Landscapes, as such, have implied tangible resources, which constitute the foundation of the world we inhabit, be they air, water, a mountain or a river, and equally intangible human attachment and cultural valuation of these resources.

Landscape is also, as W.J.T. Mitchell (1994) has argued, a “medium”. While it is a tangible context, a physical place and environment, it can at the same time be a representation of other entities, an intangible arena within which ideas are exchanged and powers enacted. Yet, we predominantly address landscape as polity (Olwig, 2002) rather than a pictorial representation.4 The underpinning of the idea of a right to landscape is our framing of landscape as more than a material object or objective environment. Landscape can be seen as a relationship between humans and their surroundings (Egoz, 2010). This relationship is shared by all human beings and as such can be understood as a universal existential bond that is part of the human experience (Tuan, 1974). The relationship is at once conceptual – a mental picture of the world that is culture and place specific, and physical – the action of shaping land and natural resources to fulfil human needs (Makhzoumi, 2010).

Perceptions are rooted in culture as much as they are in natural setting, changing from one place to another, evolving over time. Implying the ongoing complex and evolving relationship between humans and their surroundings, landscape becomes a medium for action and a political arena. Landscape is thus the locus where multiple physical elements such as water, food or shelter unite with their meanings (Pungetti, 1999).

Human rights, by definition are the rights stemming from a universal moral standard that transcends any national laws. Human rights discourse itself is not free of political tensions, in particular the problematic notion of universalism versus cultural relativism, which has drawn intellectual debate (see Bell et al., 2001; Cowan et al., 2001). Nevertheless, the establishment of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948 in the aftermath of World War II atrocities was an aspiration to guarantee both concrete needs for survival and the spiritual/emotional/psychological needs that are quintessential to the human experience. While landscape is place, nature and culture specific, the idea transcends nation-state boundaries and as such can be understood as a universal theoretical concept similar to the way in which human rights are perceived. By expanding on the concept of human rights in this context of landscape as the confluence of physical subsistence and psychological necessities we offer a new framework for addressing human rights. This original framework can hence generate alternative scenarios for constructing conflict-reduced approaches to landscape use and human wellbeing (see Makhzoumi, 2010). Linking both universalised concepts such as landscape and human rights is a point of departure for intellectual discussion, analysis and interpretation of situations where human rights are under threat.

This dynamic and layered understanding of landscape is the first step towards the intellectual interface between landscape and human rights. Accordingly, we conceive of the right to landscape as the place where the expansive definition of landscape, with its tangible and intangible dimensions, overlaps with the tangible needs for survival and the intangible, spiritual, emotional and psychological needs that are quintessential to the human experience as defined by the UDHR. The overlap between landscape and human rights, with the tangibles and intangibles related to both is represented in the diagram in Figure 1.1.

1.1 Conceptual diagram: The overlap between landscape and human rights

Book Structure

A variety of interdisciplinary perspectives of looking at the idea are presented in this volume. Each chapter may stand alone as it represents a particular account and its authors’ reflections on the right to landscape. Although chapters are grouped into parts, there is no hierarchy in terms of the significance of the right to landscape in one context or the other. Indeed, the complexity of the concept means that themes addressed in most chapters would overlap. The grouping of the chapters into five parts is an attempt to provide structure for clarifying our argument for contesting landscape and human rights.

Part I includes the general concepts that establish the new discourse. Part II aims to convey the diverse nature of the subject hence the four case studies in this section cover and address various seemingly disparate examples. In Part III the case studies revolve around indigenous people. One of the particularities of an indigenous population’s bond with its lived-in environment is that it exemplifies some of the core issues of our discussion. Part III therefore highlights the conceptual differences between a right to land as a tangible artefact that can be divided and traded gaining legal status, as opposed to landscape that embodies qualities that are difficult to quantify. Part IV presents examples that illustrate some of the dilemmas and contestation entrenched in landscape and claiming a right to landscape. The last section, Part V, covers the visionary aspects of the right to landscape concept revolving around the theme of recovery. A more detailed account and discussion of the ideas is offered below.

Part I: The Right to Landscape: Definitions and Concepts

Discussing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in the face of resource scarcity is the way in which Stefanie Rixecker, political scientist and former Chair of the Governance Team of Amnesty International Aotearoa, New Zealand, engages with the question of the right to landscape. Rixecker provides a review of past structures that had recognised a relationship between the state of the environment and human rights. She notes that effects of climate change will afflict on wellbeing both in terms of threats to the basic physical components that underpin livelihood and the prospects of increased armed conflicts over scarce resources. Rixecker ascribes the failure of the 2009 Copenhagen summit to address an urgent moral obligation as well as the lack of resolutions to assume responsibility for the consequences of developed natio...