![]()

Part 1

Experiencing place

The sensorial experience of a place extends well beyond its visual aspects, to include the smell of the dust and the trees, the day-to-day routine and repetition of actions that occur in that place, the changing weather patterns, the artificial and natural light, the sounds emanating from the life in and around the place, and even the tastes associated with visiting a particular type of built environment. These chapters all operate at the intersection of lived experience and art or architectural practice, and they each encourage a reconsideration of place that moves beyond the purely visual. Whether engaging in a network of relations between the river and the city that largely ignores it, or addressing the traumas and everyday violences (and successes) in an urban slum, a texture of the everyday shapes the ways in which these art historical studies approach their subjects. Ritual practice, whether in a local temple linked to larger royal networks or in one of a series of soup kitchens set up to serve travelers, gives us powerful repeated sensorial experiences, from daily worship to the taste of honey on the tongue. Deprivation and pollution, exclusion and struggle also mark the experiences traced here, experiences circumscribed and shaped by the places they inhabit, even as the people producing art and negotiating these spaces challenge the everyday norms and seek different configurations of place and experience.

![]()

1 “And in the soup kitchen food shall be cooked twice every day”

Gustatory aspects of Ottoman mosque complexes

The most archaic origin of architectural space is in the cavity of the mouth.

Juhani Pallasmaa1

An important component of many mosque complexes built throughout the Ottoman Empire’s long history and extensive territory was the soup kitchen (imaret).2 In these kitchens, food was cooked and distributed to the poor and needy, as well as to the many employees working in and around the mosque, tomb, schools, caravanserai, hospital, and other dependencies. Their expenses were paid via charitable foundations whose administrators produced voluminous documentary evidence. In fact, soup kitchens became one of the signature institutions of the empire, promoting the ruling dynasty’s beneficence and imperial vision (and taste). The seventeenth-century Ottoman travel writer Evliya Çelebi, in his multi-volume Seyahatname (Book of Travels), wrote:

I, this humble one, have traveled for fifty-one years and in the territories of eighteen rulers [meaning, he traveled as far as Vienna in the north and Upper Egypt in the south] [and] there was nothing like our enviable institution. May the beneficence of the House of Osman endure until the end of days.3

In his descriptions of Ottoman mosque complexes and other monuments of the places he visited, Evliya Çelebi not only mentioned the building’s form and appearance (such as the loftiness of the mosque’s central dome), but he also gave ample space to the food distributed from the imarets there, thereby creating a link between the visual and the gustatory experience of architecture. Using this link as a springboard, this chapter will explore the following questions: what types of food were served in, and therefore associated with, imarets? How was the form of imaret buildings shaped by their function as public kitchens? How did contemporary Ottoman authors express these associations between taste and the built environment? And, most importantly, in which ways did architecture and food work together in order to create a multi-sensorial experience of the space in and around early-modern-period mosques in the service of the Ottoman imperial and religious identity and vision? Finally, what can this specific case of an Ottoman monument contribute to the literature on the sensory within architecture?

In order to answer these questions, I will not only ground myself in an analysis of the architecture of mosque complexes and soup kitchens, including their location, but also draw from literary sources and particularly from endowment charters, as they are preserved in various archives in present-day Turkey. Especially the endowment charters are a rich source for details: they describe the motivations and intention of the endowment founder and the endowed buildings, both revenue-generating and charitable, and they also include information on the employees involved in the preparation and serving of the meals and the types of foods and tastes that the mosque complexes offered at specific times.

Following the emergence of sensory anthropology together with the “sensorial turn” with its emphasis on embodiment and materiality in the 1990s (after the “linguistic turn” of the 1970s and the “pictorial turn” of the 1980s),4 art and architectural historians have begun to incorporate to a much greater extent sensory modalities other than sight into the study of objects and monuments. Historians of art and architecture now acknowledge that worshippers – irrespective of their faith – did not experience worship spaces as they are usually reconstructed in scholarship, which heavily relies on mechanical reproduction techniques that privilege sight, in the form of ground plans and photographs on paper faintly smelling of printing ink. Architecture of any type of function is always multi-, inter- and trans-sensorial; however, particularly temples, churches and mosques encapsulate complex interactions among visual appearance; the kinetic and sonic effects of religious ritual; the olfactory effects of incense and other fumigatories; the haptic effects of ritual objects, furnishings, textiles and building materials; and the gustatory effect of foods associated with worship – the bread or host of the Christian communion, and the food distributed in the mosque complexes’ soup kitchens. Because worship practices universally combine sensory modalities in their purpose to communicate religious knowledge, the anthropologist David Howes has aptly termed this complex interaction “the multi-sensorial message of the divine.”5

Architectural historians have now begun to consider sound and smell as significant elements of the built environment – one may refer to Deborah Howard and Laura Moretti’s Sound and Space in Renaissance Venice, or to Bissera Pentcheva’s The Sensual Icon.6 Yet, with the exception of the essay collection Eating Architecture,7 taste has thus far been neglected, maybe because of its presumably tenuous relation to architecture.8 (Here discussions of the concept of “taste” as aesthetic preference are disregarded because of their specificity to the “Western” context.9) If that is the case for “Western” art history, it is even more so for Ottoman architectural history, which until recently remained wedded to a formalist paradigm and has only over the last two decades or so begun to incorporate more firmly contextualism, gender, and other theoretically informed approaches. However, thanks to the previous work done by scholars researching the history of food and diet in the Ottoman Empire,10 it shall be possible to elaborate on the relation between the sense of taste and the built environment.

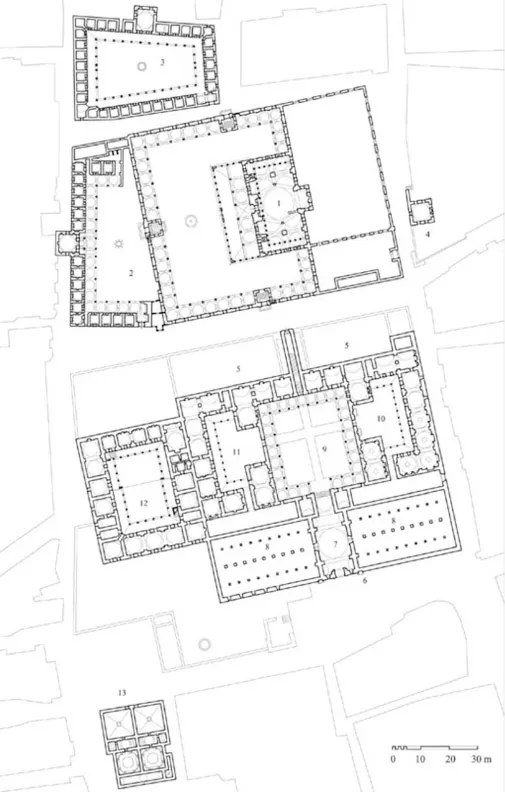

The first of the two mosque complexes that serve as case studies here is located on the hills behind the Asian shore of the Bosphorus. Built by the Ottoman master architect Sinan (c. 1490–1588) and completed in 1583, the Atik Valide complex and its charitable endowment was founded by Nurbanu (c. 1525–83), wife to the Ottoman Sultan Selim II and mother to Sultan Murad III. Ottomans could make use of the following dependencies in addition to the mosque: a theological seminary (medrese), a primary school, a convent for mystics, schools for Qur’an recitation and hadith scholars, a hamam, a hospital, an inn, and the soup kitchen, including a refectory (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Ground plan of the Atik Valide Mosque Complex (imaret = no. 10), built by Mimar Sinan, Istanbul, completed 1583

As for the question regarding what types of food were served in and therefore associated with imarets, Nurbanu’s endowment charter helps us find some answers. From this document, we learn that

[i]n the imaret, every day food shall be cooked twice, except for the Holy Month of Ramadan, because in the days of Ramadan dishes assigned only to the fast will be cooked; she set the condition that on the other days two meals will be cooked, one of them being rice soup for breakfast, the other wheat soup for dinner; the bayram days [that is, the two major Muslim holidays] are exceptional in that, on those days, for the morning very nice and delicious dishes will be prepared: Thursdays are exceptional in that, on those days, for the morning wheat soup will be cooked, and for the evening a few different kinds of delicious dishes, as they are customary in other imarets.11

Another portion of the document describes in greater detail what would have been served for dinner:

one ladle of soup or some other stew, a piece of meat in the amount of fifty dirhem [150 grams] and a piece of bread [the type mentioned, fodula, would have been baked in the form of small loaves, and “piece” therefore must refer to an entire loaf] in the amount of 200 dirhem [= 600 grams].12

In order to feed all those who were eligible to receive meals – a total of 174 persons employed or studying in the mosque complex, in addition to an unspecified number of widows and poor among Sultan Selim II’s freed slaves, with the needy of the complex’s neighborhood receiving the leftovers (Table 1.1) – a great quantity of foodstuffs entered the kitchens: on an everyday basis, 32 kg of mutton, 150 kg of wheat for wheat soup, 84 kg of rice for rice soup, 42 kg of rice for a pilav dish called dane, 12 kg of salt, 12 kg of chickpeas, and 1.25 kg of onions were turned into the soups and pieces of meat mentioned earlier. In addition, the kitchen purchased other ingredients such as oil, starch, pumpkins, yoghurt, and sour grapes, as well as seasonings such as pepper, mastic, saffron, dried fruit, almonds, and parsley specifically intended for the rice soup (Table 1.2). Honey was also among the staples used as seasoning; moreover, it was served in small quantities to newly arrived travelers who had come to stay in the adjoining inn and were in need of a refreshment that elevated the blood sugar for a quick burst of energy in order to deal with unloading the pack animals and stowing away the merchandise.13 Although to my knowledge there are no written sources describing what merchants thought when arriving at an inn, one can easily imagine that they associated the si...