![]()

1

Introduction: Cooking, Reading, and Writing in the Late Renaissance

So the circuit runs full cycle. It transmits messages, transforming them en route, as they pass from thought to writing to printed characters and back to thought again. Book history concerns each phase of this process and the process as a whole, in all its variations over space and time and in all its relations with other systems, economic, social, political, and cultural, in the surrounding environment.1

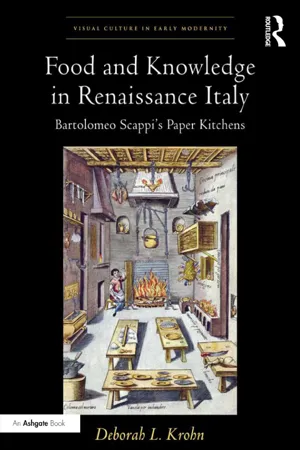

This is a book about books about cooking and serving food. It’s also about the way in which food knowledge is part of a whole complex of new thinking about empirical knowledge in the late Renaissance. At the heart of the project is Bartolomeo Scappi’s Opera, a massive compendium of recipes and menus, published in Venice in 1570 by Michele Tramezzino2 that is unique in being the first illustrated cookbook. It captured my attention in the course of teaching a class about cooking as craft practice and the material world of food and kitchens and led me to ask a series of questions that are addressed in the pages that follow: Why publish a cookbook? Why illustrate a cookbook? Who read cookbooks in early modern Europe? And the more fundamental: What is a cookbook in this period?

As a compilation of culinary recipes and meal plans, the Opera does not break new ground. Surviving vernacular recipe books date back at least to the thirteenth century in Europe, and fragmentary examples survive from antiquity. Through the inclusion of a suite of engravings, however, the Opera brought food knowledge to a higher level, creating a new paradigm for the role of images in the preparation and service of food—a paradigm that remains the dominant mode by which culinary information is stored and transmitted today. In its deployment of images, Scappi’s Opera signals a shift in the status of food knowledge from the occasional or anecdotal to the systematic or technical, indicating its creators’ aspirations to add their text to the growing body of treatises that described and categorized many areas of emerging knowledge.

Where should the cookbook as a genre be located in the burgeoning universe of the early modern printed book? Looking backwards from the present, the compendium of culinary recipes, or cookbook, can be traced as a genre of popular literature that evolved from rare ancient survivals, through a series of manuscripts that were generated within court culture, to emerge in the fifteenth century with the advent of printing. From here, the genre developed in a trajectory that shadows the rise of vernacular literature. A parallel but more elusive track might trace the history of domestic recipe collections that continued to flourish alongside printed cookbooks.3 These two strands have now joined together with the dizzying profusion of cookbooks, food magazines, television programs, recipe websites, YouTube videos, and even tweets, that promise the possibility of transforming the raw materials of sustenance into edible vehicles of personal expression for all those capable of following directions. Though the medium of delivery has evolved, cookbooks have not fundamentally changed since the Renaissance: they remain aspirational, prescriptive, and subject to the vagaries of fashion. They are also documents of the history of vernacular science. Though many historical cookbooks are mined by chefs and cookbook writers today, their contents generally appear in contemporary adaptations and interpretations that, while keeping the legacy of various traditions alive, do not reflect the historical or cultural contexts in which their sources were created.4

Scappi’s Opera is a cookbook, but I have chosen to approach it from the dual perspectives of book history and print culture, encompassing both the market for and corresponding production of printed and illustrated books, as well as the explosion of independent prints of architecture and works of art that grew steadily in the sixteenth century. As Adrian Johns has written, “any printed book is, as a matter of fact, both the product of one complex set of social and technological processes and also the starting point for another. In the first place, a large number of people, machines, and materials must converge and act together for it to come into existence at all.”5 The Opera becomes a lens through which to observe the evolving status of the cook and an emerging public for culinary literature. Food knowledge included the natural history of the edible world, the medicinal properties of plants and animals, etiquette at the papal court, and the tools and spaces used for food preparation and service.

I have benefitted from Terrence Scully’s 2008 translation and edition of Scappi’s Opera, which appeared after I had begun researching the topic and has been an invaluable source for my work.6 Despite the flourishing field of book history, which arguably began with Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin’s L’apparition du livre in 1958,7 cookbooks are not often studied from this angle.8 Book historians generally focus on books whose content is deemed significant—the Bible, the classics, literature, or history—leaving aside or dismissing with condescension the more pedestrian, “popular” printed record, in which handbooks, manuals, and how-to books figure.9 While scholarship exists on many parallel genres of early modern books, such as prayer books, playbooks, and costume books, for example, cookbooks remain less well studied as books. Were cookbooks in fact “popular”? And what does this term mean in the sixteenth century, in Italy? Printed cookbooks in Italy sold well and were presumably read by a wide variety of people—if not, they would not have been issued in multiple editions. Language is a key indicator of audience: by the mid-sixteenth century, culinary texts were almost all in the vernacular.10 Audience and readership for cookbooks is challenging to establish, but that is among the questions that my book will explore.

In situating Scappi’s Opera in the context of new initiatives in the fields of print culture, scientific exploration, and antiquarianism, among others, I am suggesting that food take part in the dialogue that has emerged in recent decades around the material culture of empirical knowledge.11 Leading the charge in these pursuits have been Paula Findlen on collecting and categorizing;12 Pamela Long on technical knowledge;13 Ann Blair and Bill Sherman on information, books and readers;14 Pamela Smith on artisanal epistemology, or what she has called making and knowing;15 Sachiko Kusukawa on the understanding of nature;16 and Evelyn Lincoln on illustration.17 In the pages that follow, these approaches will be activated as food knowledge is added to the conversation.

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 looks at the various editions of the book and what these might tell us about market, readership, and diffusion. The focus in Chapter 3 is the front matter of the Opera, including the privileges, dedication, and letter to readers, which indicated how the author and publishers sought to position the book within the emerging genre of printed cookbooks. The fourth chapter explores the group of illustrations in the Opera that depict architectural spaces, tracing the history of the kitchen, domestic and princely, and its representation in text and image in late medieval and Renaissance Europe. Book illustration is also the focus of Chapter 5, which looks at Scappi’s images of pots and pans, tools and machines, and the papal conclave in the context of the history of science, antiquarianism, and early ethnography that flourished in late sixteenth-century Rome. Connections between the book’s printers and leading antiquarian scholars and collectors of the period suggest possible authors for the illustrations. The engravings in Scappi’s Opera have not been securely attributed to a specific artist or engraver, their unusual subject matter making attribution through the traditional comparative method impossible. The images share certain formal characteristics with both antiquarian and technical illustration from the period and this is explored here. The final chapter explores the question of how this particular book was used through an analysis of extant marginalia in selected copies of the book.

Appendix A is a digest of all the copies of the book that I have personally viewed, with basic distinguishing features as discussed throughout the text as well as any notable characteristics of the individual copies. Appendix B lists the 11 editions of the Opera that I have consulted in the course of this copy census. All of the engraved illustrations for the Opera are reproduced in the original monochrome. There are also several hand-colored versions of these illustrations from a copy of the book now in Göttingen, Germany, that have not been published previously. Of the more than 75 copies of the book that I have seen, this was the only one in which the illustrations were colored. The vivid hues bring the engraved images to life, but may have been colored long after the book’s publication, suggesting that they be considered as part of the reception history of the book. I will therefore discuss them in the Conclusion.

If I have started from the model of book history’s encyclopedic purview, it is the growing field of culinary history which has shown me how food knowledge can profitably be brought into the debates about new genres and new makers of knowledge in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, a discussion which has thus far mostly been held among historians of science. Culinary history, approached through its French sobriquet histoire de l’alimentation, is largely practiced by a cross-disciplinary group of cultural historians and philologists whose research has led to the publication of serious, carefully redacted modern editions and translations of medieval and early modern cookbooks, as well as many excellent synthetic studies of recipes and cookbooks in their historical contexts. Works by Bruno Laurioux,18 Allen J. Grieco,19 Ken Albala,20 Terence Scully,21 Massimo Montanari,22 and Claudio Benporat,23 to name just a few, have provided a foundation for my exploration of the topic. Some of these scholars, and a host of others, have contributed to recent multi-volume series such as A Cultural History of Food (London and New York: Berg, 2012) and The Oxford Handbook of Food History (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), demonstrating an expanding market for culinary history aimed at a genera...