![]() PART I

PART I

From Bad to Good to Stuck![]()

1

From Bad …

Difficult Choices

Stories of difficulty in choosing leaders are all around us. Here are three, spanning organisations small to large, which surfaced in less than six weeks.

In February 2011, Time Warner chief executive fired Jack Griffin, chief executive of the group’s Time Inc. magazine publishing business, after less than six months on the job. Previously Griffin had worked at a competitor. He succeeded someone who had been with Time for more than 30 years. Within 24 hours Harvard Business Review editor Julia Kirby had crystallised six lessons for would-be corporate change agents – including not hiring cronies into the positions around you (2011).

Later that month, biographer of Warren Buffett, Alice Schroeder wrote in The Financial Times about the increasing murk surrounding the succession to the renowned investment guru (2011). Within a month the murk had deepened – Buffett’s company, Berkshire Hathaway, announced the acquisition for $10 billion of Lubrizol followed by the resignation under a cloud of David L. Sokol, one of Buffett’s key lieutenants. Since Buffett has had his 80th birthday and controls over $160 billion of invested assets, who should succeed him (and why) is a leadership choice question to rival the succession to the Pope.

These choices are no easier at the smaller, non-profit end of the scale. How difficult can it be, bankrolled by some of the world’s wealthiest and best-known individuals, to set up and build a school in a developing country? More specifically, in a country with a per capita income of less than $3 a day, how much is it possible to spend on architects, design, salaries, cars and golf course memberships without even acquiring the site for the school, now never to be built? Answer: $3.8 million. So reported Adam Nagourney in March in The New York Times (2011) on Madonna’s project to build a girls’ school in Malawi.

According to an independent assessment quoted by Nagourney, the choice of person to head the planned school was one of the contributing factors. ‘Her charisma masks a lack of substantive knowledge of the practical application of education development and her weak management skills are a major contributor to the current financial and programmatic chaos.’ The former head was barred by a confidentiality agreement from replying.

Every day board committees, senior executives and others have to choose individuals to fill positions at or near the top of organisations. As the Madonna example illustrates, even if the organisation to be headed up is small, things can go wrong. And every day these decisions have to be made by individuals and groups who cannot afford – in contrast to the examples just given – costly professional advice.

This book aims to be readable by people in the situation of having to choose leaders with limited or no access to professional advice. But it also aims to change the advice which selection professionals and researchers into the practice give. For this reason academic readers might wish to start with the introductory section of the academic notes in Chapter 14 before returning here.

The book sets its sights on fundamentally improving how we choose people for senior roles, not tricks or quick-fixes which must at best be zero-sum gimmicks as between selectors and selectees. Therefore a thread throughout the book is to take seriously the players on both sides of the selection net. After all, tomorrow’s top managers are today’s middle managers, already appointing people and offering themselves for selection.

Since its readers will already have experience (and in many cases training) in selection, the review of current good practice in Chapter 2 will concentrate on principal features: other sources will be referred to for more detail. The book’s thesis will be that it is time to choose our leaders differently: when we get to senior roles, that existing good practice lets us down. But that good practice came about through science dragging this human activity out of the Dark Ages. Not only to understand what makes our good practice effective (without which we will not understand when it might become ineffective), but also because a return to the Dark Ages is the last thing we need, that is where our journey should start: how we choose people when we do not know any better.

From the Playground to the Drawing Room

In the next section we will look at some of the scientific evidence, but first let us use our common sense. Throughout this book I will try to work with both science and common sense, including pointing out where there is reason to believe that one of the two is letting us down. I hope this will help make the book readable and practical; but in Part III there will turn out to be deeper reasons for approaching our subject in this way.

A microcosm of human selection can be found in the school playground. Many of us have memories of lining up and being picked by two captains alternately in order to form two teams. Who gets picked early and why? Most of selection is here. Someone who kicks or throws like a dream. Someone on a winning streak in their last few games. Someone influential or cool, or at least not nerdy or laughed at; someone whose group you want to be in. Someone who is already friends with one of the captains. Someone good-looking. Someone tall. Someone keen. Someone who flatters and sucks up. Someone intimidating or handy in a fight. Above all someone similar to the existing group, who fits in. Despite being tall I was always one of the dregs at the end of the process, barely worth the two captains flipping a coin over, so my memories are still vivid (sociologists call this ‘the lucidity of the excluded’). If you look beneath the disciplined language of a Harvard professor, it is easy to see many of the same playground factors at work in Rakesh Khurana’s study of how CEOs are recruited at the top of America’s largest corporates (2002).

As we grow up, we get taught how to use the correct knives and forks, but unless we are trained in interviewing, the way we select in the playground moves effortlessly into the drawing room or board room. This is beautifully captured in the poem You Will Be Hearing From Us Shortly by U. A. Fanthorpe reproduced at the beginning of this book. What she captures – the sense of interviews as a process of social gradation, with class as one significant factor – is no fantasy. As late as the 1970s this was established British good practice.

Consider this example from research at that time by David Silverman and Jill Jones (1973). They studied the graduate recruitment process of a large public sector organisation. The process was thoughtful and structured. First interviews were carried out at universities by a single representative of the employer, out of which 150 candidates (about one-fifth of those interviewed) were invited to a group process at the employer’s offices. Groups of eight candidates spent the morning in two group discussions (one on a concrete administrative problem and one on a general topic) and were observed by a panel of three selectors (senior administrators). In the afternoon each candidate had an individual 20 minute interview by the panel. Typically two or three of the eight candidates would be selected.

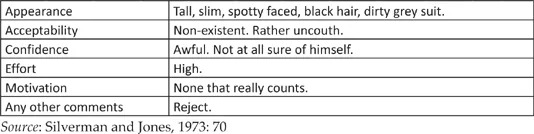

The organisation had decided that beyond the scheme’s degree requirements, they did not wish to select on intelligence. Instead ‘acceptability’ was key, as reflected in the mark-sheets which selectors used in making and recording their decisions. ‘Chadwick’ and ‘James’ are respectively one of the first-round candidates and his interviewer. This was the mark-sheet James completed on Chadwick. The interview was one of a number which were taped and later discussed with the interviewer and with other senior administrators.

Table 1.1 Chadwick’s mark-sheet

Chadwick had a cockney accent. Part of the interview noted that few people from Chadwick’s school had gone to university, to which he had applied behind his parents’ backs. In a closing exchange in which Chadwick objected to the interview itself:

J: Now, any other points?

C: Er … basically no. Interviews to me – this type of interview – I object to most strongly actually. (Silverman and Jones, 1973: 74–75)

Chadwick went on to assert – from the perspective of Chapter 2 we might say presciently – that by the end of the interview James still did not know whether a person was suitable for a position in administration, but when challenged he was unable to suggest another way of selecting people. Nevertheless Chadwick had a perspective:

J: Put it another way, what would you be looking for?

C: A logical mind.

J: That’s the mental equipment. But what kind of bloke would you look for?’ (Silverman and Jones, 1973: 76)

James reflected subsequently that he had been amused by Chadwick’s criticism of the interview while lacking an alternative approach, although neither of the things to which Chadwick arguing more effectively might have pointed (intelligence or knowledge of selection) were on the organisation’s wanted list.

Three senior administrators who reviewed the tape for the purposes of the research concurred with James’s overall judgement. Their discussion includes these exchanges:

A1: … And bear in mind, of course, that the chap, admittedly he comes from, he is slightly less well-mannered than the other people James has interviewed because of his background …

A2: I wouldn’t say well-mannered necessarily. We’ve interviewed one or two Etonians whose manners have been absolutely dreadful. But, uh, you know (laughs) … (Silverman and Jones, 1973: 71–72)

A3: What an excellent interviewer James is!

A2: Yes I liked the way he squashed the attempt of the candidate to interview him at the end of the interview [when Chadwick criticises the interview]. He just killed it stone-dead really without being rude, which is terribly difficult to do in fact … (Silverman and Jones, 1973: 94)

All this indicates that James is not a rogue interviewer but interpreting the thoughtful good practice of 1973. ‘Acceptability’ in all its nebulousness does indeed seem to be the key to this selection process. In coming from the playground into the drawing room we do not seem to have travelled far. By contrast the indignation which anyone trained in selection today may feel towards these exchanges shows how far we have moved in the past 40 years.

We make that journey in Chapter 2. What prepared us to move were scientific flashes of light in the dark, snapshots which showed us what we well-meaning selectors were in fact doing.

Scientific Snapshots in the Dark

Worrying evidence about untrained selection, and in particular interviewing, abounds.

Important in Chapter 2 will be the idea of competencies as a basis for selection and HR management more broadly. This concept was developed by Richard Boyatzis (1982), motivated in part by a scientific study of the Broadway Manufacturing Company in America. The study took people who had joined the company as supervisory managers 20 years previously and looked for objective factors which distinguished those who had been promoted most within the company from their less successful peers. Only one objective difference could be found: the more successful supervisors were taller.

Height continues to matter. Judge and Cable looked at four studies (three American, one British) totalling 8,590 individuals. Basing their calculations on the value of US dollars in 2002, they found that:

… an individual who is 72 in. [1.83 m] tall could be expected to earn $5,525 more per year than someone who is 65 in. [1.65 m] tall, even after controlling for gender, weight, and age. (Judge and Cable, 2004: 435)

Speaking of weight – more recently Judge and Cable (2011) have explored the gendered impact of weight on earnings. They conclude that across a 25-year career, American women who are 25 lbs (11.4 kg) below average weight earn $389,300 more than American women of average weight, while for American men the difference is $210,925 and reversed (the heavier men earn more).

Or – a small sample from a cornucopia of possible material – women candidates facing male interviewers should wear dark jackets (and preferably blue rather than red), while female interviewers are relatively uninfluenced by colour (Damhorst and Reed, 1986) (Scherbaum and Shepherd, 1987). Studies among managers in utility companies suggest that physical attractiveness is correlated with interview ratings as well as with assessed job performance (Motowidlo and Burnett, 1995) (Burnett and Motowidlo, 1998) (DeGroot and Motowidlo, 1999).

For many years there has been evidence that untrained interviewers are drawn to intuitive conclusions in the opening minutes of an interview and use the rest of the time to assemble confirmatory evidence. That initial judgement time was estimated at four minutes by Springbett (1958) and nine minutes by Tucker and Rowe (1977).1

Some judgements formed even before the interview starts prove difficult to displace. Huguenard, Sager and Ferguson (1970) simulated 377 employment interviews where one person interviews another. Before meeting the candidates the interviewers were given (artificial) results from a ‘personality test’ which suggested that the candidates they were about to meet were ‘cold’ or ‘warm’. Whether the interviews lasted 10, 20 or 30 minutes, the interviewers persisted in describing the candidates in terms consistent with the initial label.

In fact the selection interview is a doubly dangerous breeding ground for early impressions. However we react to someone’s height, weight, jacket colour or physical attractiveness, these things are unlikely to change during the interview. That is not so with the complex interpersonal factors with which interviews are concerned. Most interviewers’ early impressions are leaky. They rapidly communicate themselves to the candidate in different ways – eye contact, posture, tone of voice, frequency of interruption not to mention choice of words. Consciously or unconsciously the candidate is affected. The interviewer plays a major part in creating the interview ‘performance’ which she assesses. An early critique on these lines was made by Dipboye (1982). Fanthorpe’s poem in the opening pages of the book expresses this eloquently: we see the candidate vividly through the interviewer’s eyes without reading a single word of the candidate’s own.

Indeed, Arvey and Campion (1982) were able to say in what became one of the most frequently cited articles of the 1980s in the journal Personnel Psychology:

Perhaps the glaring ‘black hole’ in all previous reviews and in the current literature concerns the issue of why use of the interview persists in view of evidence of its relatively low validity, reliability, and its susceptibility to bias and distortion. (1982: 314)

That landscape has not changed. As Wood and Payne (1998) observed:

Many studies have shown the predictive validity of unstructured interviews to be around zero. (1998: 96)

One would be as well off choosing people by tossing a coin.

To all the selection-specific research we can add the extensive body of knowledge which, thanks to science, we have gained about more general problems with human decision-making. For example there have been many studies of the processes of clinical judgement which trained professionals – for example psychologists – use to assimilate complex, incomplete and possibly discrepant information about particular individuals and make a decision. Writing in the context of psychologists who assess and counsel individuals, Spengler and three colleagues (1995) highlight several recurrent problems in the formation of clinical judgements including:

• availability – paying too much attention to the parts of the evidence which come easily to mind;

• anchoring – over-weighting information which is presented early;

• overshadowing – one major diagnosis leads other complicating factors to be ignored;

• confirmation – seeking and finding evidence to support initial hypotheses rather than noticing contra-indications;

• attribution – too easily interpreting events or actions as signs of personal traits at the expense of external or situational factors.

These potential errors easily translate into selection interviews, particularly the ‘halo’ effect in which the flaws of candidates who appear good disappear from view. Only careful re-reading of interview notes which are sufficiently detailed to bring back to mind the dull as well as the vivid parts of a candidate’s answers will combat availability: taking such notes as well as participating in an engaged way in the questioning is beyond the ability of most occasional interviewers. Anchoring, overshadowing and confirmation are obvious suspects behind the overpowering effect of early interview impressions. An attribution error so often made that it masquerades as common sense is deciding that someone is indecisive who hesitates and fumbles an interview question, despite years of contrary evidence from their actions in the field.

In any of these respects, the judgements even of trained employment interviewers are hardly likely to be better than that of clinical professionals – quite apart from the lack of objectivity involved if the decision will be whether to make the candidate a colleague of the interviewer’s.

Selection at Senior Levels

By now it would be reasonable to accept that, at least in the absence of contemporary good practices, selection can be a fraught activity. The Dark Ages were dark.

However they were also some time ago. Good practices along the lines of those summarised in Chapter 2 have been around in some form for 20 or 30 years. Moreover the reasonable person might expect more than average care, effort and expense in t...