![]()

1 Opening Places

A perspective on place enables us to consider how a particular locale—a classroom, community, town, after school club, or website—is not an isolated container, but positioned in a nexus of relations to other such locales … as classrooms or other sites of learning are seen less as parking lots and more as intersections, then the particular mobilities of people moving through them become a key issue for evidence and equity.

Leander, Phillips & Taylor, 2010: 336

Just as our skin provides us with a means to negotiate our interactions with the world—both in how we perceive our surroundings and in how those around us perceive us—our language plays an equally pivotal role in determining who we are: it is The Skin That We Speak (original emphasis).

Delpit, 2002: xvii

A Study of Youth in Contemporary South Africa

This book explores how young people from one Cape Town neighbourhood, an area that was constructed during apartheid, learnt differently in classrooms, by comparison with when they were participating in other educational places. For three years I followed students into the local high school and interacted with a hip hop crew that wrote lyrics and performed in the same community. I also facilitated a radio show where youth from this area shared their thoughts and ideas live on air, in conversation with peers from other schools. I have used these three educational sites to create a journey that moves across the lives of young people from this neighbourhood, illuminating the progress made in post-apartheid South Africa by highlighting some of the opportunities available to its young citizens. The different sites are held together by the fact that young people from Rosemary Gardens1 engaged with a range of ideas and people and expressed their own views, through language, in each of the three places.

These three interlinked sites shed light on how youth in troubled, unequal societies, like South Africa, learn in different educational places. Since the beginning of the South African democracy, the world has watched this new country unfold, amazed at the largely bloodless negotiated settlement, but wondering whether the racial reconciliation is genuine and if sustainable economic redress is possible for one of the world’s most unequal societies. South Africa represents a testing ground or case study for racial and economic justice everywhere. I did the research for this book believing that there is no better way to observe developments in this multiracial social experiment than to interact with the generation who are growing up in it, listening to their dreams and frustrations and assessing what their futures may hold.

Young people born in the post-apartheid era, such as those who feature in this study, long for an improved quality of life and the chance to become upwardly mobile, valued members of their society. These are opportunities that many South Africans assumed would accompany democracy. Yet change has been slow. Some changes have taken place. Old draconian laws that separated and oppressed people labeled by the apartheid government as ‘black’, ‘Indian’ and ‘coloured’ have now been replaced by some of the most progressive legislation in the world. For example, the new Child Justice Act (2008) is underpinned by a restorative justice framework that does not advocate for retribution for child offenders. Instead the act stipulates that perpetrators and victims of crime should be reconciled. The South African Schools Act (1996) ensures that local communities, in the form of parents, constitute a majority on School Governing Bodies.

Besides developing new legislation, there have been other achievements. The new government, led by the ruling African National Congress, has delivered services to large numbers of the population. Some 85% of households now use electricity for lighting, compared to 58% in 1996. In 2011, 77% of the population lived in formal dwellings, with the government building 2.6 million houses between 1994 and 2009 (Statistics South Africa, 2011).

The government’s social assistance programme consists of a number of non-contributory social grants, including pensions for the elderly, disability for those who cannot work and a child grant for parents. Some 16.1 million people now receive social grants, which make up the main source of income for 22% of households (Republic of South Africa, 2013).

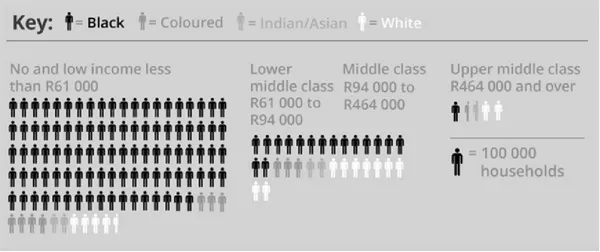

Despite these admirable legislative and service delivery developments, material transformation has been frustratingly slow. The average annual household income for black South Africans is R60,600 (approximately USD $4,500),2 whereas it is R365,000 (approximately USD $24,000) for white South Africans (Statistics South Africa, 2011). Sixty percent of South African children grow up in households with a monthly income of less than R575 (approximately US$40) per person per month, with 67% of black children growing up in households that live below the poverty line compared to just 2% of white children (Hall & Chennells, 2011). Income inequality is also increasing rapidly within race groups. Significant numbers of black South Africans have joined the upper classes, yet inequality and the number of poor and unemployed people have grown exponentially (Seekings & Nattrass, 2005).

Figure 1.1 South African income categories by race

These class- and race-based divisions are rife in Cape Town, the city that forms the focus of this book. Cape Town is essentially two cities: a wealthy one that lures foreign capital and tourists, and one characterized by urban ghettos of underdevelopment. Mcdonald (2008) says that Cape Town may in fact be the most unequal city in the world. The very high rates of violent crime are indicative of these unresolved class- and race-based inequalities.

For the young, urban poor these outcomes are infuriating. They do not dream about owning a two-bedroom government-built brick house and having access to electricity and a social grant. These young people want challenging and exciting jobs. They want to own houses in nice neighbourhoods. The lifestyles and commodities they observe in the media and which adorn middle- and upper-class youth remain largely unattainable for most of the urban poor. Neither are these young people fooled by glib terms that the new state creates, concepts like the ‘rainbow nation’. There is a general air of disappointment, of great expectations and small gains that have been acquired very slowly.

Three Interconnected Learning Places

The media, government and large sections of the general public perceive education to be vital to remedying these setbacks and accelerating transformation. Many of the ‘born free’ generation, as the group born post 1994 is sometimes called, buy into this belief that schooling is the best way to escape poverty and realise their aspirations. It is certainly true that the qualifications that schools confer remain essential in the global era, as it is very difficult to obtain a good job without completing high school. However, it is also true that schools, like most social institutions, reproduce power relations such that poor children go to poor schools and get badly paid jobs. It was important for me to investigate how school may create and/or limit opportunities for youth in Rosemary Gardens, meaning that this institution was an important research site. I tried to capture this group’s experiences of ‘the school’ by spending time in classrooms, listening to their interactions with educators.

School is not the only place that stirs hope in young people. Youth often experiment with who they are and who they would like to become in informal educational places. These sites allow them to explore their passions through activities like music, dance and grappling with new ideas. In informal educational sites youth engage with products from global and local popular culture and are often able to learn on their own terms. Hip hop rap songs are one example of how youth mix, play with and reinvent language in many parts of the world (Alim, 2009). Hip hop is now the world’s most popular subculture, with young men and women using this genre to experiment with forms of language and identity in diverse settings like Palestine, Senegal and Brazil. Hip hop is especially appealing to poor black youth, who use this cultural form to occupy public space through their words, graphic art and breakdancing. I stumbled upon the Doodvenootskap hip hop crew through spending time in Rosemary Gardens. It was obvious to me that the young men involved in this group carried a great sense of purpose in the work that they performed and that they perceived enormous potential in participating in this forum, making it an important research site.

The third and final place that features on this journey is a youth radio show that was broadcast live and made use of interactive social networking tools. Youth Amplified had an accompanying Facebook page and participants interacted with the public through text messages and telephone calls. Informal learning places, like this radio show, in conjunction with new technologies such as the Internet, cellular telephones and social networking sites, provide young people with opportunities to express themselves through using language to reclaim public places. The three sites therefore formed a unique expedition across the lives of young people from one Cape Town neighbourhood.

I have used these formal and informal educational contexts to illuminate the lives of youth from Rosemary Gardens, providing glimpses into how they learnt in and between sites, as they assessed and optimised the potential that these places held. The three places were selected through an unfolding, organic process. Or, perhaps I should say that this is one interpretation of the research ‘plan’. Interesting sites emerged as I was introduced to new people, as I traced and followed social connections and networks across different locations. On the other hand, the research that makes up this book could be understood as a project that I pre-designed, arranging interactions with people and making ‘customised’ contexts, such as the radio show. It would also be true to say that part of the story I tell in this book emerged in retrospect, as I pieced together different people, activities and histories, creating a coherent narrative. Each of these three interpretations of the research process that makes up this book is partially true. Research is a messy business, particularly in low-income South African neighbourhoods where ‘quiet’ is a scarce commodity and convenient places for conducting interview conversations tend to be elusive. What I can say, with confidence, is that I spent a great deal of time in one poor neighbourhood that I will call Rosemary Gardens, ‘following’ a range of people, primarily youth, in an effort to tell a larger story. This larger story is about how young South Africans learnt in different places as they participated in dialogues with other people, in the hope of one day realising their aspirations. Let me give a little bit more detail about the three places.

Site 1: Rosemary Gardens High School

At the time I started this study I was employed by a Cape Town–based NGO called the Extra-Mural Education Project (EMEP), an organisation that worked at a local primary school in Rosemary Gardens. EMEP facilitated extra-murals at more than 40 schools in the Western Cape province, using these activities to promote schools as hubs of their communities. I developed a special relationship with a number of the staff at a school in Rosemary Gardens, a school I will call Mountainview Primary. This led to my facilitating leadership sessions at the high school in the area, in collaboration with a colleague who had grown up in Rosemary Gardens. Together we tried to create an orientation programme for students entering the high school from Mountainview Primary.

The Rosemary Gardens High School that I became familiar with was very different from the caricatured South African township school that exists in the media. In the media and in the imaginations of many who make up the South African middle- and upper-classes, schools in neighbourhoods that were formerly reserved for ‘black’ and working-class ‘coloured’3 children are generally thought to be dysfunctional places. These schools are associated with textbooks that do not arrive until late in the academic year, if at all, as demonstrated by the widely publicised ‘Limpopo textbook crisis’ (Veriava, 2013). It is assumed that large numbers of teachers at such schools are regularly absent and that they rarely spend time teaching in the classroom. Students are believed to learn very little at township schools and it is thought that they instead dedicate most of their time either to criminal and/or gang-affiliated activities, being pregnant or abusing various substances.

There is indeed some truth to these perceptions, but this picture is only one view of township schools. The whole truth is far more complex. Rosemary Gardens High School (RGHS) had access to textbooks, as well as to sports fields and coaches. At the school there were two computer laboratories, a library and a gymnasium. On most days, one or two of the 38 educators may well have been absent, but the vast majority arrived at school and spent a great deal of time in classrooms, delivering the school curriculum. The school offered a large number of activities and resources to its students. A free meal was available to all students who wanted to eat at school and many chose to receive food through this programme known as the ‘feeding scheme’. The school offered a range of afternoon activities, as well as access to resources like books and computers. A number of entrepreneurial projects took place on the school grounds. Ben 10, an NGO that refurbished, rented out and sold bicycles, operated from a prefabricated structure at the front of the premises, and the school farmed lavender, a plant that was used to produce cosmetics and beauty products.

Despite offering this array of activities and services, the school suffered from very high rates of discontinuation. There were over 400 grade 7s and only 60 grade 12s in 2012, a consistent trend in recent years. This confused me. How could a school that offered dance, music, sports, extra lessons in the afternoons, as well as computer laboratories, a Virgin Active gym and a free meal, be so unappealing to young people who had access to few opportunities and resources?

The school appeared to have the benefit of good leadership, moreover, which increased my bewilderment as to why so many youth did not want to spend time at school. The principal, with whom I became close, was a man I greatly admired. He was a political activist during the apartheid era and held a MA degree which focused on participatory teaching and learning at RGHS. RGHS has also had stability in its leadership, another factor that experts pinpoint as important for school effectiveness. The school was erected in 1978 and has only ever had two school principals during its existence.

I needed to understand why so many young people stopped attending this high school and so I spent as much time as possible in classrooms and at school-related activities. I interviewed 15 teachers one-on-one and conducted focus groups with half of the grade 12 learners. Thirty students participated in the focus groups: one of the two matriculating classes was chosen at random and then divided into groups of four or five. I asked the students questions regarding what they enjoyed and did not enjoy about school and encouraged them to describe life in their classrooms and neighbourhood. I also probed what learning meant to them.

I was often invited to functions at the school, including the prize-giving, as well as other events that involved dignitaries from the Western Cape Education Department and speeches by the patron of the School Improvement Programme (SIP), who is a prominent academic. In these meetings I met a number of local education department officials and later interviewed some of them, probing their personal perceptions o...