![]() PART I

PART I

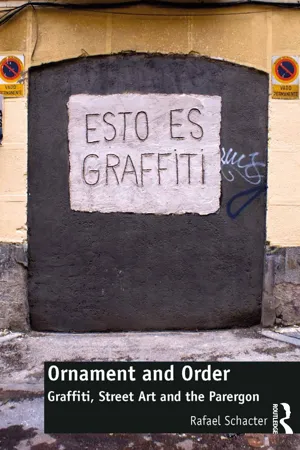

Ornament![]()

1

Ornament

The man of our times who daubs the walls with erotic symbols to satisfy an inner urge is a criminal or degenerate […] With children it is a natural phenomenon: their first artistic expression is to scrawl on the walls erotic symbols. But what is natural to the Papuan and the child is a symptom of degeneration in the modern man.

Adolf Loos

[W]e are all of us criminals by instinct. It is part of our very nature […] If we act in defiance of custom or reinterpret custom to suit our private convenience we commit a crime; yet all creativity, whether it is the work of the artist or the scholar or even of the politician, contains within it a deep-rooted hostility to the system as it is. On that account creativity is mad, it is criminal, but it is also divine.

Human society would have died out long ago if it were not for the fact that there have always been inspired individuals who were prepared to break the rules.

Edmund Leach

LOS CHOQUITOS Y LOS CARTELES

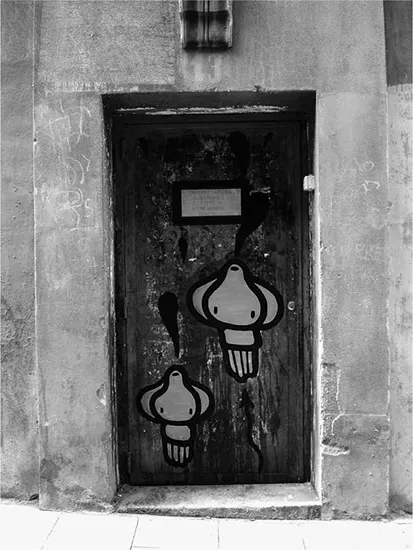

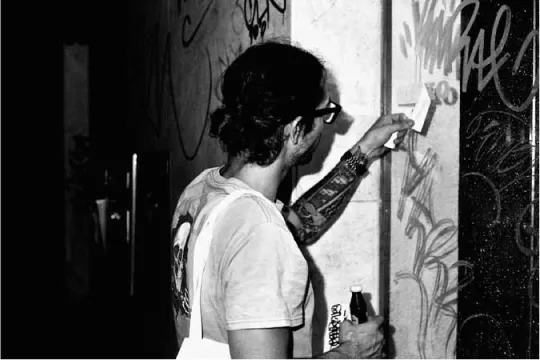

Nano’s choquitos, or ‘little squids’, are all over Madrid. Not just Madrid in fact, they’re plastered over every place he visits. Remnants of himself on the walls of the city. Manifest traces of his personhood materially covering the world. These plump, innocent looking cephalopods, floating around the metropolis, spraying the city with their dense, sepia ink. When I think of Nano they’re one of the first things to come to mind. An image of him leaning on his bike, surreptitiously inscribing his mark on to the wall, a smooth flowing movement of his arm and like magic they appear. ‘I just need to do it,’ he’d say, never feeling able to fully explicate why, ‘even when I work with bigger institutions, in galleries or inside, I just feel this constant need to get back to the street and to bombing … It’s the same feeling I give everything, a tag,1 an installation, whatever. Never for self-promotion, but for self-expression’. So there they sit, his choquitos, amongst the grime and coarseness of the stone, ‘like a metaphor for the writer in the street’ he once said; ‘I was thinking about the way they both moved around quietly at night, the ink they both use, it just seemed like the perfect symbol’. There was a huge choquito I remember seeing the day I arrived to meet Nano in Berlin, a massive bright orange squid spurting black ink all over the walls and the surrounding imagery. I was searching for him and Eltono, the battery on my phone had died, I was without a map and only had the address of the warehouse where they were working and some pretty appalling German. On seeing the image I remember feeling a visceral relief, almost as if I’d seen Nano himself.2 It meant simply that he couldn’t be too far off, that at the very least he had been there previously … Nano was always crafting these choquitos, painting them everywhere he went. In phone boxes and on lampposts. In doorways and on shop-grills. In underground tunnels and on 12th-storey window ledges. Always on something. Always working with the physical medium at hand. Working around the tags, the signs, the dirt, the contours of the surface, with the shapes and the form of the city.3 You’d turn around and he would have disappeared, only to then spot him lagging behind in a doorway marking up the final arrow or filling in the last bit of ink. A final flourish with the implement at hand (whether a marker, a can, a key), and then an immediate departure from the scene.

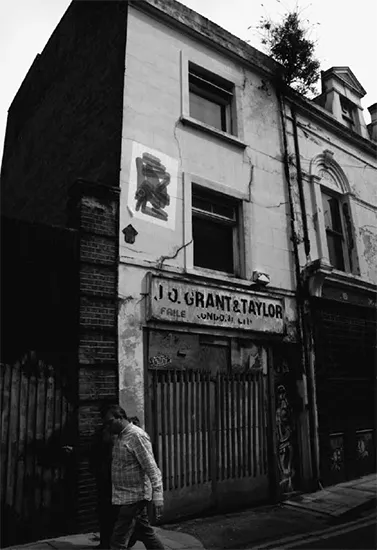

1.1 Nano at work, Madrid, Spain, 2009

1.2 Nano, Untitled (Choquito), Madrid, Spain, 2007

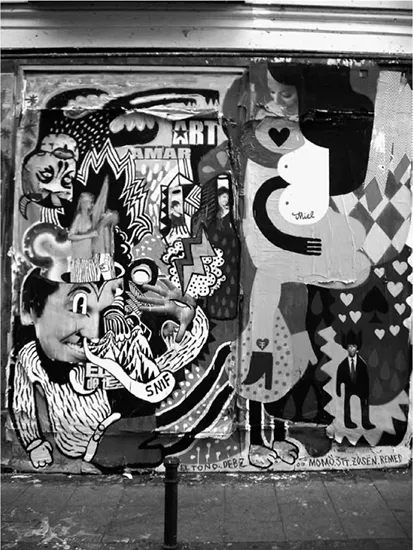

1.3 3TTMan, Untitled (Carteles) [detail], Madrid, Spain, 2008

With 3TTMan4 it’s the carteles that first spring to mind,5 these unmissable, uncompromising, polychromatic collages which he would produce in the very centre of the city. On Gran Via, on San Bernado, huge 20-foot-long productions lining the key arteries of the city, works formed on top of the densely packed palimpsests that were the (semi-legal) bill-posters which consumed nearly every single vacant or neglected edifice in the city. For 3TTMan, it was considered to be his first ‘successful’ venture in the street, by no means his earliest artistic foray into this arena, but the first project he thought really connected, that he was fully content with. Unlike Nano – whose City-Lights project (see Plate 4) had in fact been a huge inspiration for 3TTMan in his search for a new way method of production in the city – 3TTMan disliked working directly on the surface of the city’s walls (‘the stone is good’ he’d say, ‘it doesn’t make sense for me to work there’), his previous works thus for the most part having been produced on what is termed street-furniture, on traffic signs, recycling containers, concrete bollards and the like. It was not that he disliked other forms of illicit visual production that worked directly onto the street, simply for him it did not feel like the right surface for his work.6 In coming to use the bill-posters as a site of production,7 however, an already present addition to the city, an already present canvas to be re-worked in situ, 3TTMan managed to find a site he felt fully liberated to work upon. He would thus play with both the words and the imagery, destabilizing and challenging them, trying to make people enjoy rather than just disdain or ignore the posters. It was not simply a project aimed at questioning notions of consumption and consumerism that 3TTMan aimed to produce here, it wasn’t a direct form of ‘adbusting’ or ‘culture-jamming’ however; the work on the carteles was about taking a form of communication ‘imposed to your eyes’, something outside the field of relationality, and turning it into something you could ‘connect to’, something that you could ‘think about in a more interesting way’. As he once told me, ‘I just want to make the people who pass by laugh, to turn the carteles into something you can interact with, to put some life back into the space’. It was thus all ‘about the medium and the location’ for 3TTMan, all about playing with what was at hand; it was about working with, détourning the very materiality of the city.

1.4 3TTMan, Untitled (Carteles), Madrid, Spain, 2010

ADJUNCTIVE AND DECORATIVE

Be it Nano’s choquitos or 3TTMan’s work on the carteles (or, for that matter, Eltono’s geometric designs [see Plate 1, alongside the artist MOMO], Remed’s mystical murals [see Plate 5], or Spok’s multilayered street tags [see Plate 8]), these unequivocally spatial works existed within the medium of the street, amidst the dirt, the cacophony, the very concreteness of the city’s walls. They were not produced on a neutral surface (on a pristine canvas or from moulded clay), not presented on a discrete tabula rasa (formed from scratch, or ex nihilo). They were not created within a separated studio space (within a disconnected, insular, private zone) nor within a detached white cube (within the ‘disinterested’, passive milieu of the gallery). These material acts were engraved onto the very surface of the city, scraped onto previously constructed forms. And, in this way, these works thus comply quite succinctly with the first part of the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of ornament, functioning as an ‘accessory or adjunct’ – a secondary element on a primary surface, an auxiliary element on a customarily architectural plane. As ‘sgraffito’ (etymologically originating from the Italian graffio, a ‘little scratch’), these objects can only be truly apprehended in connection to what they were scratched upon, always, by their innate status, being produced upon, within, or fixed to a secondary surface. They thus exist as a literal mura rasa, a scraped or scratched wall, the ‘what’ of the image (in this case either Nano’s choquitos or 3TTMan’s collages), being ‘steered by the how in which it transmits its message’ (Belting 2005: 304), through their being scored onto an architectural body (in the former case) or a palimpsestic commercial residue (in the latter). To ornament, as Oleg Grabar has suggested (1992), the ‘act of putting something on something else’ – rather than a term attempting to describe the specific ‘nature of what is put’ (ibid.: 22) – can thus here be seen to be exactly borne out. These ‘sgraffitos’ (whether the most elementary tag or the most complex mural, whether a kinetic installation or a wheat-paste poster), are all material forms placed upon supplementary surfaces, and must therefore be primarily understood through their additional, subsidiary nature. Consequently, what I will first be arguing within this chapter is that all my informant’s public aesthetic production must be understood to be fundamentally ornamental in this adjunctive sense, they are works which only exist through the body of a secondary medium and are hence steered, activated though the ‘how’ of the city itself.

Furthermore, be it again Nano’s choquitos or 3TTMan’s carteles (or for that matter 3TTMan’s further work on concrete [see front cover], Nano’s City-Lights project [see Plate 4], Eltono’s confetti graffiti [see Plate 2], Remed’s polychromatic calligraphy [see Plate 6], or Spok’s futuristic, comedic murals [see Plate 7]), these now unambiguously adjunctive artefacts all functioned within the sphere of the decorative, of the beautiful, within the realm of what Brett (2005) has termed ‘visual pleasure’.8 Working thorough both a ‘public’ and yet simultaneously ‘intimate’ form of visual pleasure, a material sensuousness and playfulness which may act as a marker of ‘social recognition, perceptual satisfaction, psychological reward [or] erotic delight’ (Brett 2005: 4), these artefacts embraced the captivation and gratification that the figural admits, the enchantment that both the production and consumption of images provide. Whether in their most overtly aggressive or ‘vandalistic’ form – such as a throw-up,9 an acid etching (see Figure 1.5),10 or a ‘keyed’ insignia – or in their most apparently amicable or ‘decorative’ state – such as an elaborate mural, an abstract poster (see Figure 1.6), or a calligraphic message on a wall – all of these forms of cultural production were created within a complex tradition of visual dexterity and physical skill, containing a quite defined notion of aesthetic value and beauty at their core (even if a naturally subjective notion of beauty of course). Qualities such as ‘order or unity, proportion, scale, contrast, balance and rhythm’ (Moughtin, Oc and Tiesdell 1999: 3) – elements understood as the key principles of decorative production – were fundamental to these particular designs, basic tenets which determined their latter formation. Even if they were constituents that these practitioners sought to establish only so as to later defile, if they were used to form a contrast to, or a coherence with their architectural surround, the basic structure of all the public works my informants produced could only become visible through working with and through these underlying decorative principles, principles which formed distinct styles irrelevant of their perceived aesthetic acceptability. These were decorative criteria meant to make the object ‘selectable, meaningful, affective and complete’ (Brett 2005: 64), qualities meant to enliven the objects on which they appeared. And what I will thus secondly argue within this chapter is that the material practices described above were all produced specifically to ‘decorate, adorn, embellish [and/or] beautify’ their surfaces, and thus all comply quite faithfully with the second half of the OED’s definition of ornament.

1.5 Neko, Untitled [Acid Etching in process – etchings also visible in surround], Madrid, Spain, 2010

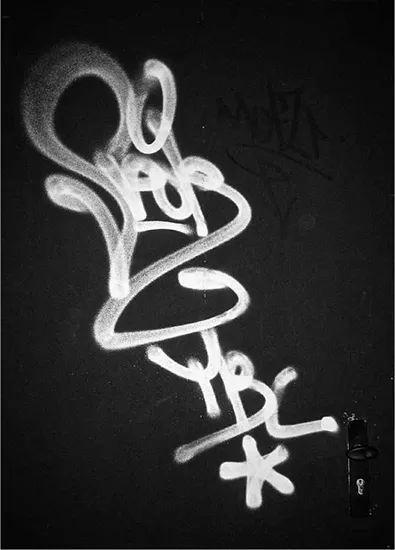

If we very briefly explore one of the most prominent examples of Independent Public Art then (and one often thought of as the most artless or ‘lowest’ by those outside of the discourse itself), this being the commonplace practice of tagging, we can see how this oft described scribbled mess, this supposed territorial pissing, is in fact a doubly ornamental practice. Whilst its negative appreciation may be due to the innate lack of curatorial delimitation within Independent Public Art, the fact that the work of the neophyte and the expert is equivalently available to public view, one can find an almost perfect coherence between this notional pollution and what is deemed as more classical calligraphy. Emerging through both their formal as well as conceptual nature – through the crucial elements of unity, proportion, scale, contrast, balance and rhythm that are paramount in the production of every example (as we will see specifically in our case studies on pp. 78–86, 115–26), through the linguistic discourse and legendary masters that both groupings contain, through both practices attempt to supplement and embellish standardised typography – these two forms of “beautiful writing” (in their Greek etymology) can be seen to be fundamentally indistinguishable.

1.6 Momo, Untitled, London, England, 2008

1.7 Katsu, Untitled, New York, USA, 2011. Katsu’s figurative icon, produced in one pure movement, functions both as an image of a skull whilst also containing the word ‘tag’ hidden within it

1.8 Spok, Untitled, Madrid, Spain, 2007

Yet as earlier suggested, tagging can not only be seen to be ornamental through its status as an adjunct and adornment of the letter form, it can so too be seen to be acting adjunctively upon its architectural surround as much as the word, the ‘what’ of the image – the written name – guided through both the ‘how’ of the letter as well as the ‘how’ of the city itself. It is thus doubly ornamental, embellishing typography and architecture, supplementing the word and the wall. And even though often deemed ‘incomprehensible’, as Grabar (1992) suggests almost all calligraphy is, these written texts can thus come to ‘elicit a very special response from viewers’, an ‘emotional or psychological reaction’ (ibid.: 58–9) culminating either in pleasure or disdain, the pleasure of the aficionado or the disdain of the authorities (yet either response being a successful one of course). Just as calligraphy is understood as one of the archetypal forms of ornament, so too tagging must be seen in the same way, as an accessory and an embellishment to a secondary structure, as an adjunctive and decorative aesthetic.11

Not only tagging but all the illicit artefacts that are to be discussed within this text are thus, I would strongly argue, the perfect examples of the ‘applied decoration’ that Brett argues is the essence of ornament (ibid.: 4). They are decorative markings working through what Tom Phillips sees as the elementary foundations of all ornament: ‘form, line, tonality, material, disposition, [and] colour’ (Phillips 2003). They are ornaments which function as intermediaries through which ‘messages, signs, symbols, even probably representations are transmitted, consciously or not, in order to be most effectively communicated’ (Grabar 1992: 227), markings which act to transmit both ethical and aesthetic values. And this, in fact, is perhaps the key proposition that I aim to make within this work as a whole, or, at the very least, a proposition which will simultaneously order and enrich the rest of this work itself: whether constructive or destructive, these illicit artefacts are both decorative and adjunctive, they are accessories to a primary surface, forms of embellishment upon an ancillary plane, and hence objects with a fundamental ornamental sta...